This early-career collection from prolific Noah Van Sciver presents stories culled from anthologies such as MOME, Alternative Comics, Van Sciver’s one-man Blammo, and more. Van Sciver, who grew up in hardscrabble circumstances, is best known for his painfully funny, incisive-yet-sympathetic portraits of lower-middle-class twenty-somethings, barely scraping by in quiet desperation. But anyone who has read Blammo or seen Van Sciver’s widely anthologized comics and one-shots knows that his talent is far-ranging. His body of work mixes the trademark slice-of-life tales with short pieces that range from the mordant satire of the cartoonist’s life in “It Can Only Get Better!” to the absurdist sci-fi monster-splatter of “Punks vs. Lizards”, the hilariously grotesque horror of “I Could Be Dreaming”, and three relatively straightforward fairy tale comics (one a Van Sciver original, the other two adaptations from the Brothers Grimm). His talent is evident throughout Youth is Wasted, and even with the mix of content and genres, it’s a strong, unified collection, with all of the stories sharing a gritty, unromantic tone.

Van Sciver's caustic, plainspoken characters harbor few illusions. With their generally diminished life expectations, they sense tough times ahead. But the luckier ones sense that while things aren’t going to be easy, they aren’t completely hopeless either. Take Grant, the protagonist of the poignantly funny “Because I Have To”. The story is set on Halloween night. Grant, grieving the loss of his little brother in a car accident a year before, tries to wax poetic about the coming winter. (“The wind takes the fall away from me eagerly. It violently strips the trees bare like a rapist in an alleyway.”) But he stops himself, as if embarrassed by his thoughts (“I’m no poet”). He then happens upon a tearful little girl named Matilda in a witch's costume, who was separated from her brother while trick-or-treating. Grant tries to shepherd her to safety (while helping her continue visiting houses for candy), but gets nothing but grief for his trouble. He nearly gets run over while rescuing Matilda from traffic, and when he at last reunites her with her brother, he's knocked down and accused of being a child molester. Kindhearted Grant experiences the axiom "No good deed goes unpunished" in this misadventure, but he resignedly moves forward anyway: “Because I have to.” In another story, “Expectations”, Kramer, the brokenhearted hero, attends a party even though he knows his ex-girlfriend Nikki will be there. He can’t resist seeing her, and the results are predictable: she ends up in tears and his wounds feel fresher than ever. Still, like Grant, Kramer sucks it up, firm in his resolve to let go, though still haunted by the past: “Looking backwards while walking forwards is no way to get somewhere.” Van Sciver mines genuine pathos from both stories without descending into sentimentality.

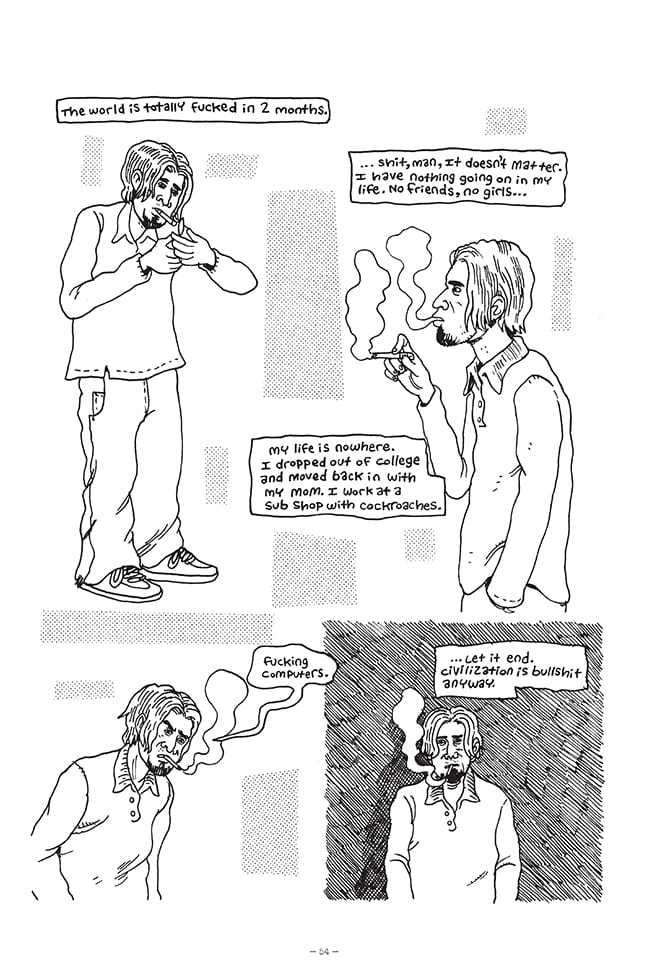

In other comics, the protagonists don’t even have Grant or Kramer’s meager reserves of inner strength and hope. Ill educated, trapped in dead end jobs or desperately unemployed, they unwittingly sabotage themselves at every available opportunity, ruining relationships and prospects, and even physically hurting themselves. At the outset of "1999", the longest, bleakest story in the book, anti-hero Mark sees a talking head on TV warning of the ramifications of Y2K, the big non-event that was expected to threaten the global economy at the very start of the millennium. The talking head asks, "How can we, humankind, utilize Y2K as an opportunity to look at ourselves, to analyze where we've been and to adjust our sights to the future?" Mark's answer to that: "Let it end. Civilization is bullshit anyway." Living with his mother and working the night shift at a dingy sub shop, he enters into an affair with a married coworker named Nora. When that connection ultimately doesn’t work out, Mark spirals down – way down. He in effect “Y2K’s” his own future, and it isn’t pretty.

Van Sciver states in his endnotes that he's known a lot of people like Mark and that he is drawn to them. His ability to realistically yet sympathetically limn his characters, presenting them in their full warts-and-all human dimensions, is one of his greatest strengths as an artist and writer. It’s a Crumb-like ability, actually, especially in “Who Are You, Jesus?” where the sad-sack title character has a lapse in moral judgment and pays dearly for it. Van Sciver is one of those artists – like Seattle's Max Clotfelter – whose comics strike me as the missing link between today's alt-comics scene and great old '80s and '90s-era anthologies like Weirdo and Street Music.

In sum, Youth is Wasted serves as a fine capper to the first stage of Van Sciver's still young career (he just turned 30 this year). AdHouse did an impeccable job on production and design, complete with French flaps with drawings snuck underneath them. Van Sciver’s older brother Ethan, a cartoonist who works on superhero titles for DC, wrote the rather touching introduction, in which he clearly demonstrates his pride in his younger sibling’s talent and perseverance. Van Sciver's always been a talented draughtsman and has worked doggedly to continue to evolve. For example, compare his rendering in 2010's "Abby's Road" with his work in 2013's "1999" for evidence of his increased confidence and visual sophistication. Then find a copy of The Lizard Laughed, his solo minicomic released this year by Oily Comics, for further proof of his ever-expanding verbal and visual mastery. Noah Van Sciver works hard for the money, and the proof of pudding is well presented on these pages.