In the hands of Ed Piskor, his character Kevin "Boingthump" Phenicle (a composite based on several real-life computer hackers and phone phreaks) acts as a blank slate to help him tell four very different but linked narratives. Piskor's obviously scrupulous and obsessive research allows him to tell stories about phone phreaking, hacking, how to live as a fugitive, and the ins and outs of prison life. Phenicle is a narrative device for Piskor to expand upon and explore this wealth of research, and he becomes less approachable as a character the more the story unfolds. Wizzywig (the onomatopoeia for WYSIWYG, a computer acronym that stands for What You See Is What You Get) very much lives up to its title--even as a satirist, Piskor doesn't go in for subtext or subtlety in this book. Given the crazy stories he bases this book on, that's not a surprise.

At the same time, Piskor clearly has his work cut out for him in drawing a book that features a lot of sitting around. He always has the reader in mind when illustrating a scene, breaking the book up into easy-to-digest vignettes, man-in-the-street features, look-ins on other characters, and flash-forwards to Phenicle's prison experience and railroading by the justice system. That affords him the opportunity to easily jump back and forth in time, but it also makes his historical anecdotes easier for a reader unfamiliar with the subjects at hand to digest. He switches between Kevin's friend Winston doing a radio show and various people listening to what he has to say, to Kevin as a kid going about his day (with no other narration), to Kevin narrating images via caption (with no word balloons), to having Kevin and Winston in the background of someone else's story, to a mix of caption narrative and dialogue, to an omniscient narrator commenting on Kevin's lack of self-esteem. When his characters have conversations, Piskor often depicts them walking and in different poses from panel to panel--anything to keep a reader's eyes moving across the page. Piskor is also careful to let his pages breathe a bit, including the occasional panel that doesn't necessarily advance the narrative but does provide a beat or two to slow the story down a bit. His art is mostly naturalistic, with the occasional stylistic flourish. Piskor is mostly about moving along the story. That said, he always adds a certain decorative touch even in talking head scenes; he always goes the extra mile to give us interesting people to look at. I especially like the way he draws hair--scraggly hair and beards on men, odd curls and swoops on women. He revels in the grotesque, creating characters with slumping postures, unkempt hair, shaggy eyebrows, and bad skin.

Piskor begins the book with a series of talking heads, all discussing assorted legends surrounding Kevin. Some folks think of him as a dangerous criminal, others marvel at his remarkable skill, and others perpetuate rumors, legends, and tall tales about him. We're then introduced to Winston Smith (one of many winks to the reader by Piskor), Kevin's boyhood friend, who serves as one of the primary narrative devices in the story. While Kevin's interest in hacking was almost purely a type of intellectual exercise, Winston was more fascinated by its political (and otherwise anarchic) possibilities. Piskor quickly establishes a central struggle for his protagonist, and it's not an unfamiliar one: a technical wizard struggles to connect with other humans, especially girls.

Piskor manages to evade cliche with this tact through a number of clever devices. First and foremost is his character design. Kevin has blank eyes, much like Harold Gray's Little Orphan Annie (an idea seemingly inspired by Chester Brown and his Louis Riel). Indeed, Kevin is an orphan who lives with his grandmother, and it's clear that being yanked out of his loving environment at a young age has much to do with his social ineptitude. At the same time, the blankness of those eyes reveals a certain sociopathic streak--the flip side of social ineptitude. Kevin is unable to physically confront the bullies that torment him but strikes back at them by hacking phone systems and making their lives miserable invisibly. While Piskor clearly has a certain fascination with the abilities of hackers like Kevin, he leaves a layer of ambivalence in his portrayal. That ambivalence plays out as Kevin does try to connect with others and frequently fails as a counterpoint to his otherwise superhuman hacking abilities, especially when he uses "social engineering" experiments to steal from and manipulate others.

Kevin is very much a "can-do" character like Annie, using his wits and skills to outfox adults. Skirting the law is more a matter of testing the limits of his abilities than any real desire to cause harm, whether it's ripping off software for redistribution or delving into the deepest bowels of the phone company. Unlike Annie, Kevin winds up paying for his mischief in the harshest manner imaginable. Piskor satirizes the media in the face of a local muckraking TV "journalist" in the mold of Geraldo Rivera, who sensationalizes Phenicle's crimes and drums up hysteria regarding his motives and abilities. The FBI and Ma Bell are only too happy to have public opinion set squarely against Kevin, given the way that he embarrassed both of them for so long. Piskor isn't exactly subtle in this satire, as the reporter is all but foaming at the mouth in describing Phenicle.

The first and second halves of the book are radically different in terms of tone. The reader is aware that Kevin is in prison without even receiving a trial, but most of the narrative follows childish hijinks and an exacting level of detail regarding phreaking (manipulating the phone system with a variety of tricks) and hacking. The reader essentially gets a primer on both subjects that clearly fascinate Piskor, stretching them over the bones of a narrative. With his TRS-80 computer, Kevin hooks into early bulletin board systems (BBS's) but quickly grows bored, even when screwing with a particular BBS whose members hate him (as an aside, having a member with the ID "Godwin's law" compare Boingthump to the Nazis was a stroke of genius). This leads him to copying game software for quick resale, but a virus he stuck into each game as a joke ("Boingthump owns your soul, sucka!") winds up as an augur of his eventual doom (as well as getting him his ass kicked in the short term by angry gamers). When a teacher of Kevin's invites him to be part of an inaugural computer science course at his high school, Piskor inserts the narrative of a jealous classmate who rattles off some more of Kevin's hijinks. Kevin later manages to talk his way into the phone company's inner office to steal all sorts of useful information, which he uses in small ways (altering bills, charging phone sex numbers to people's lines, etc.) for his own amusement. That is, until he learns that the phone company was aware of his computer accessing theirs, which sent the FBI after Kevin.

The second half of the book begins with Kevin as a fugitive, gaming the system so as to create new identities as he moves from town to town. There are many images of Kevin sitting in a library, going through records so as to establish his new identity of the moment. Piskor embraces depicting the mundane aspects of the hacker lifestyle, choosing to remain true to details rather than try to make the stories sexier but less true-to-life. Of course, as Kevin tries to elude his pursuers, it does help that there are some actual chase scenes to draw, but these make up only a very small number of pages. The most interesting aspects of this part of the book are the real-world guides to living as a fugitive, like a step-by-step set of instructions on how to create a new identity, the best way to squat in a vacant house, and how to run any number of hustles if you sniff out the right sort of low-life (like a pimp or movie producer looking to spy on his wife).

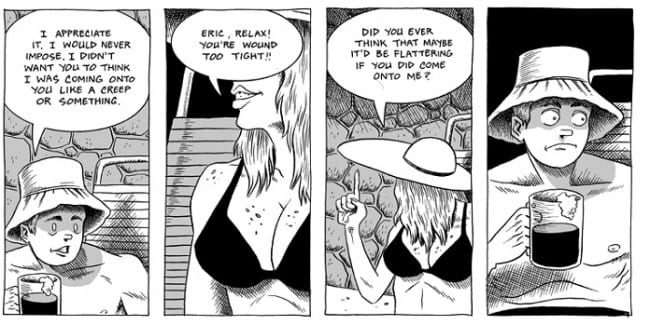

Kevin becomes even more of a non-person in this chapter, as he literally has to remake himself constantly, both in terms of image and personality. That’s one of the ways Piskor manages to keep the book visually interesting: by presenting a wide array of outlandish hairstyles, clothes, and disguises Kevin uses while trying to stay one step ahead of the law. When dealing with women in this chapter, Kevin pretty much sees them as a means to executing one of his many lucrative money-making schemes. For example, Kevin likes rigging the outcomes of radio contests and uses women to accept the public prize (like vacations), taking cash and other items for trade. He finds the prospect of sex with any of these women to be greatly unnerving.

In earlier chapters, one always has a sense that when Kevin engages in “social engineering” experiments to bilk people out of things he wanted, he tends to see most other people as a means to an end. As a fugitive, that is the only way he could see other people. Piskor contrasts the misery of a life built on sand with a flash-forward (told through the radio show of his friend Winston) of his hellish day-to-day existence in prison. While that last chapter still has certain underground DIY elements (like how to make the most of your prison cell), it's mostly a grim and repetitive series of scenes that builds up to an explosive climax. Piskor tries to tie together a number of narrative threads in this final chapter and doesn't quite do it in a satisfying fashion. Characters like the reporter get a comeuppance, but in the end, Kevin is too much of a blank slate for the reader to really care about. Piskor tries for poignancy in the final scene but it falls a bit flat, as Phenicle's serious injuries in prison scar him emotionally as well as physically. Because the reader has only a passing acquaintance with his emotional state, it lacks the cathartic power that I believe Piskor intended.

Ed Piskor is one of my favorite young cartoonists, in part because his subject matter is such a left turn away from his peers. He's also unusual in that he takes a lot of his inspiration directly from underground artists like Robert Crumb and Jay Lynch, as opposed to more contemporary influences. There's a nice looseness to his work that sometimes manifests as a certain sloppiness with lettering and spelling. I was surprised to see this in the book, given Top Shelf's fairly tight editorial oversight. Overall, his lettering is attractive and clear, but he sometimes drops letters or tries to cram them in awkwardly. The design for the book is clever and funny, one of many nods to the early days of the personal computer revolution that Piskor inserts into the book. Wizzywig was crazy in its ambition as a first major solo work by a young artist, and one can sense that Piskor learned a lot from the experience. We'll see how this sort of self-made comics PhD program accomplished in future projects.