Wille & Joe: Back Home is the follow-up to the massive, impressive collection Willie & Joe: The WWII Years. That latter work was just reprinted in softcover format by Fantagraphics. The softcover, clocking in at close to 700 pages, lacks the pizazz of the hardcover but certainly gets the job done. Bill Mauldin's career was lightning in a bottle, a combination of luck, timing, talent and a point of view that many could understand and relate to. A novice cartoonist at the time he was drafted into the army, his chops and perspective were honed in a remarkably short period of time thanks to what he saw on the front. While he did not engage in combat, he spent a considerable amount of time in combat zones and knew the ins and outs of daily GI life. As such, his strip, featuring the unshaven & cynical soldiers Willie & Joe, boldly depicted the drudgery of a soldier's life, the hypocrisy of commanding officers and the frequently ludicrous logic of the military.

Remarkably, he was given a lot of leeway to draw his single-panel strips, which were featured in Stars and Stripes, a military newspaper that every soldier read. By giving a voice to the grunts, the higher-ups deemed it an important way to let off steam and even improve morale. Not every officer felt this way (General George S. Patton famously chewed Mauldin out), but Mauldin spoke truth to power from a very early age. Mauldin became famous thanks to reporter Ernie Pyle spotlighting his strip and wound up winning the Pulitzer Prize. What was remarkable about his sudden and powerful popularity in the US was that his message ran counter to the the military, media, and entertainment industry's depiction of the experience of the soldier.

Willie and Joe weren't upbeat, apple-cheeked GIs who were rah-rah about "seeing action." They were grizzled, beaten-down, exhausted workers who were there to do a highly unpleasant job in the best way they knew how. As the men who were fighting and dying on a daily basis, they resented those who put them in harm's way while staying out of the fray. They resented draconian and arbitrary rules laid down by officers and enforced by MPs. They resented opportunists who never spent a day on the front line by tried to claim glory for themselves. ]That Mauldin was able to tell their stories was impressive, but the fact that he managed to do it with jet-black humor that everyone could relate to was remarkable. The public was obviously hungry for these kinds of stories, and despite the cynicism there was always a ray of hope to be found in the World War II strip. That hope was fueled by camaraderie and trust in one's fellow GIs as people who understood the insanity whirling around them. One knew where one stood with your buddies standing next to you in a foxhole.

Coming back from war was another matter. As his biographer Todd DePastino reveals in the introduction, Mauldin did not want to continue to write about his two characters. In fact, he wanted to kill them off in his last WWII strip. However, "lots of people were making good money off Mauldin" and he had a contract to fulfill. That contract stipulated four cartoons a week, which is a pretty substantial output for an artist who wasn't simply coming up with situational gags. If he was going to be forced to do his strip, Mauldin was going to air out all of his grievances with how veterans were treated and America in general. That led to any number of battles with his syndicate, especially as Mauldin's work became more overtly political.

If Mauldin's World War II strips were a needed corrective to the public's glorification of war, then his post WWII work fulfilled the same function for those who thought of post-war America as some kind of euphoric utopia. Indeed, the reception given to those soldiers who actually served in combat and were haunted by what they experienced seems to have been closer to the Viet Nam experience than one would expect from the popular images one associates with the end of the war. Mauldin even addresses the iconic images of girls kissing sailors on the street, noting that those servicemen were the ones who hadn't actually seen combat, while those who had survived four years of hell were still stuck overseas, trying to dodge being shipped over to Japan. America adjusted when much of its young workforce was drafted and there was resentment from those that didn't fight when soldiers came back looking for jobs.

The first year or so of his post WWII strips continue to follow Willie and Joe in civilian life. Willie is back with his wife and a young son who had never met his father. The reunion, depicted one panel at a time, is not a smooth one. There is constant fighting and the revelation, as subtly depicted in one brilliant strip, that neither spouse was exactly faithful when they were apart. The division of the military into those who fought and those who didn't continued to plague the grunts in civilian life, as soldiers who never saw time on the front not only demanded special treatment (and were the ones getting it in the early days after the war ended) but outright scorned the now ex-soldiers as being "4F," not knowing what they had experienced. Enlisted men, having received no useful training in the army, were having trouble finding jobs in a country that was just starting to emerge from a Depression.

After a few months of this, Mauldin clearly grew tired of thinking up new variations on gags on how his soldiers were adjusting. After all, Willie & Joe were everymen, and he could only go so far in using them to comment on issues that went far beyond simple readjustment. Mauldin was becoming more interested in tackling racism (with a number of daring cartoons that took the KKK head-on), anti-immigration tendencies, censorship, sexism and Red scare politics. Mauldin admitted that some of his early attempts to address these issues were failures, saying, "I said to hell with everybody and let fly with a sledge hammer, when I should have used a needle. Cartoons are no good if they are soapboxy and pontifical. They have to be thrust gently, so that the victim doesn't know he's stabbed until he has six inches of steel in his innards."

The back end of this volume sees Mauldin transform from observational cartoonist with a political bent to a full-fledged editorial cartoonist. The transformation was not a smooth one. Mauldin's politics were impressively progressive and his boldness in taking on unpopular topics & targets was admirable. However, he became a standard "labeler" as a political cartoonist—literally writing words like "socialism," "imperialism," and the names of various countries on his drawings so as to explain his message. I've always found this to be an incredibly lazy style of cartooning and it certainly didn't seem fitting for a cartoonist of Mauldin's caliber to take such shortcuts in order to score easy points.

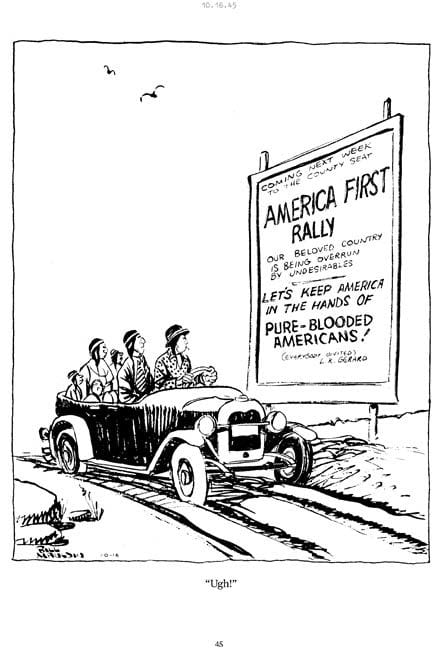

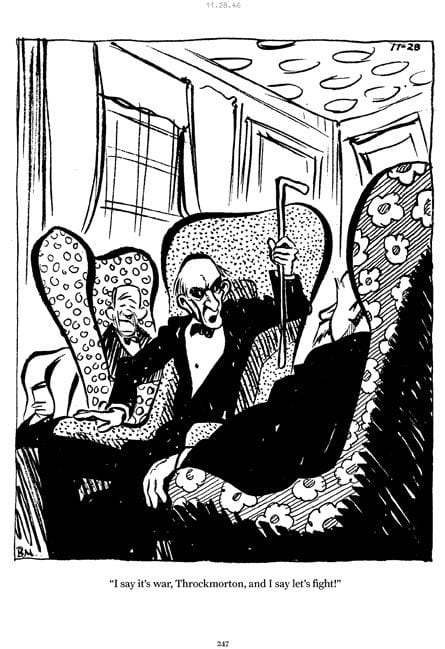

There are still some gems to be found in this book, however. A car full of Native Americans saying "Ugh!" to a poster advertising an "America First Rally" dedicated to the idea of "Let's Keep America In The Hands Of Pure-Blooded Americans!" is clever on a couple of fronts—both the concept itself (revealing the hypocrisy of the poster), and the punchline (turning racist/stereotyped "Indian" dialogue into a genuine outburst of disgust). One of Mauldin's most famous cartoons finds two old gentlemen sitting in a parlor. One of them angrily raises his cane, his sunken eyes flashing with rage, and yells, "I say it's war, Throckmorton, and I say let's fight!" It's the epitome of Mauldin's anger in this volume: the old, rich & privileged putting the young, poor and powerless in harm's way in order to support a bankrupt ideology, and in essence, their own egos.

The production values for this volume, like the hardcover edition for The WWII Years, are impeccable. It's a jacketless, clothbound book designed to match that first volume with a mustard yellow to complement that camo green. DePastino's introduction is jammed with illustrative biographical details and is livened up with promotional materials. Mauldin's art in these strips simply isn't as interesting as his WWII material. The contrast between lovingly-rendered and naturalistic weapons & vehicles and the cartoony figures is absent. Backgrounds are sometimes scrawled or sketched instead of getting real detail, although his figures are still wonderfully expressive. There are exceptions, of course, like a GI laying on a bench in a park, with a cop looking over him. It's a marvelously composed image backed up with a funny punchline. The quality of Mauldin's line is still great, especially in the way he draws crease lines on clothing and depicts the slouching postures of his characters. Still, one gets the sense that his drawings aren't as labored over simply because there wasn't as much at stake. Having to crank out that many strips per week certainly couldn't have helped matters any, which led to the use of some shortcuts and repetition of subject matter.

Back Home is a study of an artist in transition, both in terms of his art and his life. At the same time, it's a study of a nation in transition, where the political and cultural ground was shifting and a battle over the nature of that national discourse was being waged. It's nowhere near the achievement that the last couple of years collected in The World War II Years and frequently shows the strain of a man unhappy with his life (his marriage disintegrated not long after he came home) and his career. It's a bridge between his war cartoons and his later, more sophisticated career as a straight political cartoonist. As such, it's of far greater interest for historical and even biographical reasons than for aesthetic ones.