While it served as the definitive memento mori for centuries, the image of the skull became played out through overuse in the late twentieth century, circa the publication of the Appetite for Destruction album art. Afterwards it only signified a sort of toughness arrived at via nihilism, becoming increasingly ubiquitous and concurrently watered-down. Noel Freibert has been drawing skulls (in a cartoony way that might also suggest a head with rotting flesh or some kind of ghost) and placing them on the cover of his magazine Weird since 2012's issue 1. Inside, Freibert included comics with such skulls situated alongside images of crucifixes. He seemed to be attempting to imbue them with a particular meaning, so that they would be seen as a torture instrument rather than a symbol of faith in the divine. To me, it didn't work, and despite the quality of many of the comics contained in Weird, their intentions existed inside a cultural noise that needed to be seen past. Images of upside-down crosses primarily recall metal music, and while some people might be freaked out by the Satanic implication, few of them were likely to be reading Weird Magazine.

The new issue of Weird almost entirely consists of Freibert's comics (earlier issues are multi-artist anthologies), three chapters of a piece called "Spine". The spine is a more appropriate vehicle for Freibert's concerns than the skull. Michael DeForge once wrote on Twitter that Freibert's comics capture the sensation of physical pain better than anyone else. The spine is a precarious and delicate stack of bone that contains and supports your nervous system, and as you age, the chance that you associate it with a location of physical pain increases.

The spine stands at the center of the body, while Freibert's comics have increasingly become concerned with negative space, the frame around the structure. Each page of "Spine" has more blank space framing the comics than necessary, and each is marked with the name "Spine" along at least one of its borders. Consider the front cover. The image of the spine, which Freibert depicts by giving each vertebra its own face, is consigned to the book's spine. The rest of the cover is defined less by a central image than by textural elements of grime. It seems as if bandages were affixed, color fields applied either with silkscreen or spray paint, and then the bandages removed, leaving only imprints. Meanwhile, another Band-Aid keeps the title affixed to the cover, hanging by a little flap.

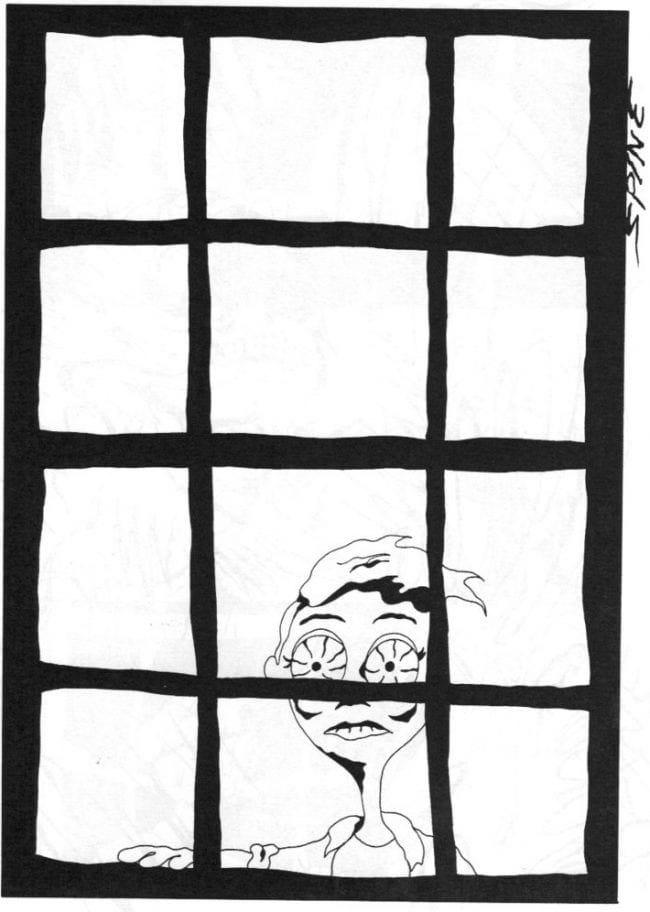

The Band-Aid, that gross and flimsy thing, serves its own symbolic purpose. It is the cheapest, most readily available form of health care available, and this is what the comic is all about: The complete absence of health care, a source of pain both physical and mental. Reading the comic, we are introduced to a character who is covered in bandages, Band-Aid over his nose, dripping snot.

It is very similar to a one-panel comic Frank Miller drew for the benefit of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, showing a child whose eyes are x'ed out by overlapping Band-Aids, tears dripping out from under them, her ears and nostrils covered in a similar fashion. A final Band-Aid is about to be applied to her mouth by a largely off-panel authority figure, saying "Good girl. Just one more -- and you'll be safe." It is a disturbing and powerful image. In the light of Frank Miller becoming increasingly right-wing in the years since he drew that image, and the right wing's present appeal to free-speech arguments to defend hate speech against the marginalized, it's an interesting détournement to contextualize a Band-Aid-swaddled figure in terms of the necessity of health care for all.

Before founding Weird Magazine, Freibert made a series of horror comics that existed in an obvious lineage that led from EC Comics through undergrounds and work in Warren magazines created by the likes of Richard Corben. These had a "host" character, and depicted transgressive acts. It was easy to see Weird as intended to follow in this tradition, with its title's similarity to Warren magazine publications like Creepy or Eerie. However, pretty quickly, within the context of the more obvious horror stories made by his fellow Weird contributors, the work Noel was making himself attempted a more Beckett-influenced sort of blankness. Now, with those other contributors absent, the horror has moved away from anything approaching genre tropes. Once a mood used to discuss the inevitability of death in semi-humorous fashion, now it is more of a Mark Beyer-styled wail of terror, an ambience necessary for discussing life in America. The humor present, evident in his even older zines, is this sort of slack-jawed vacant-eyed caveman Beavis and Butt-head, taking-acid-and-watching-Faces of Death thing. The imagery interpretable as "heavy metal" that I found so gauche can then be understood as related to this, as an attempt to signal that his sympathies lie with this sort of figure. They exist in a timelessly vulnerable position, that being the kid in a tribal society who eats the unfamiliar berries to find out whether or not they're poisonous. The politics are essentially an outgrowth from that vulnerability, the result of an artfulness that attempts to achieve a state of thoughtlessness, somewhere adjacent to zen but reflecting absolute brutality and decimation.

The "Spine" these comics are named after is the the town where they take place. It is "the backbone of suburban America." The water is poisoned. At the time of this writing, water that is unsafe to drink is an affliction that has not hit suburbia. It is obvious, common even, to make work about "suburbia" as this dangerous, soulless place, that is spiritually dead. Freibert's work takes spiritual deadness as a given, a prerequisite. He can also presume that the audience reads suburban settings with an expectation of satire. By putting the issues that people living in cities have to deal with into this setting, he is working as a satirist, but also effectively prognosticating.

Still, in the third chapter, a character emerges from a curbside garbage bag to say that nothing is wrong. This voice insists that "Spine is a fake comic," and that the residents are happy. This denial both reads as a further satirical point, but it is also obliquely recognizable as a horror technique. It's true that people watching the news are as likely to be freaked out by the Trump administration's repeated denial of obvious facts as they are by the facts themselves. In Blake Butler's experimental novel 300,000,000, a horror narrative premised on everyone in America murdering each other, contradictory accounts and frameworks are given continually. A form that insists on its own reality, without breaking the fourth wall, is easier to parse and understand than what happens here. The chaos that emerges when an author allows a work to contradict itself places the reader in an unstable position. Rather than allow the reader a supposedly objective foothold by which to view the narrative, the fiction dissolves into its authors originating impulses of unresolved dread. The effect is similar to the moment in Rosemary's Baby when Mia Farrow exclaims, "This is no dream, this is really happening." Only by refusing to make distinctions between reality and nightmare, the reader, entangled with the subject of the story, is refused the reprieve of the peacefulness of sleep.

All of the formal strategies Freibert employs in "Spine" come from horror. For all the cartoony proportions, the inky forms used to delineate their shape captures them in an unnatural light. The globs have the sheen of blood in a giallo film. When the panels are at their barest, figures existing in largely blank space, dripping lines slash across the page, suggesting a score: Either the dissonant upper-register strings Bernard Herrmann would compose for a Hitchcock film, or the shrieking industrial noise of the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre. This effect is compounded by the sludgy, dreary pace the comic suggests, across pages where nothing happens, a drawn-out approach influenced by manga's approach to conveying feeling. Here that means a two-page spread where the outside of a clothed body in contrasted with a vision of the interior as a thing of ribcage and nerve endings. There is an aggressive willingness to be unpleasant.

If one is viewing this "art comic" in the tradition of fine art, the work looked to would be not just Mike Kelley, but also the performance work of Chris Burden. Luckily, while it might have been thematically appropriate for this issue of Weird to be crowdfunded online, in the same way people pay for life-saving medical procedure, the printing of the issue of Weird is paid for by Koyama Press, in advance of their printing Freibert's graphic novel Old Ground this Fall. This issue of Weird, completed after that book was finished, I believe, has presumably been in the making since before Trump's inauguration. While I see plenty of talk by artists wondering how to make work in the age of Trump, if you've been engaged in the world, aware of societal undercurrents, and making work about your anxieties before, your approach does not necessarily need to change. Trump's winning the electoral college may have surprised you, but things have been apocalyptic for a while now. Many of the people whose lives are most endangered by a Trump administration have been feeling under attack for a while, and so saw the possibility of his victory as more likely than others who would perhaps be more insulated from the effects of his victory. Freibert has been making politically-engaged work at least since Ferguson. A one-page strip in a previous issue had a teenager declaring "we live in a fucking police state."

This more political approach emerged at the same time as Freibert was playing up the elements in his work that were less based on genre, and more textural and conceptual. While working on writing this piece, an idea of an object occurred to me that relates to Freibert's work more than all the other comics or horror work I have mentioned previously. It is the idea of a washcloth, having fallen onto the bottom of the tub after washing oneself in the shower. If you, not noticing it is there, pee on it accidentally, the symbolic weight of it would be similar to what is present in "Spine". Its texture is loaded down with different kinds of wet and film. The feeling of something intimately acquainted with you becoming gross when you had your back turned and were not paying attention, is how America feels right now to its residents, and the texture of filth and grime this issue of Weird captures points to why.