Climate change, when it’s not visible in a sweeping, violent fashion, can be difficult to perceive, more present for some people as a looming abstraction than a felt, measurable thing. This might be why, during the last two decades, few depictions of climate change in the arts have captured the cultural imagination, despite its planet-wide implications. This absence informed the Kickstarter campaign for Warmer. Editors Andrew White and Madeleine Witt told visitors to the campaign page, “We both spend a lot of time thinking about climate change. [...] And we haven't always found art that reflects that.” An anthology of comics about the climate crisis, Warmer at least fills a void within alternative cartooning, exploring personal experience within a global phenomenon.

Warmer is about as cohesive as anthologies get in terms of tone and sensibility. It includes, for instance, multiple past contributors to the Comics Workbook Tumblr, multiple six-panel grid compositions, and multiple works of colored-pencil cartooning (though without full overlap among these categories). Consider it the hazard of a coherent editorial vision—a sense of monotony might set in if a person reads too many pieces in one sitting. A spirit of contemplation characterizes many of the comics, which often feature soft colors and other formal choices that convey quietness, perhaps at the expense of other sensations (e.g. outright panic). Even so, this is a result of Warmer attempting something challenging.

Warmer is not a book of mourning, at least not exactly. (Witt’s piece with Anya Grenier, for instance, is about the possibility of human resilience.) And that’s appropriate. Living as bystanders to climate change—or marginal, fitfully guilty contributors to climate change—doesn’t mean grieving in the normal sense. And then of course there are the times when a person might not want to think about it at all. This is Warmer’s contribution: its artists work to depict a consciousness of the climate crisis, a feeling without a name, somber, implicating, contradictory, and unique to this massive, fearsome process.

Wenting Li’s piece examines the tensions of living with climate change—staying aware of the latest crisis while also staying present within one’s own immediate environs. It’s a brief, two-spread work with some resonant images: dead fish at a person’s feet, juxtaposed with a panel of the figure’s hair beneath a showerhead; a massive wave sweeping a house away in the distance, while the figure waits for a bus in the foreground. Graeme Shorten Adams provides another four-page piece with striking juxtapositions. In his comic, Adams nods to the temptation of magical thinking with respect to climate change, mixing images of flowers and wet garbage, a sunny island and industrial exhaust. Although his approach is starker than Li’s, it’s another effective study in contradictions.

Kimball Anderson’s contribution is the anthology’s final piece and one of the most outwardly mournful. It’s not the most arresting comic—at first glance, it looks like another wispy pencil piece—but Anderson establishes real powers of pacing and expressiveness. The comic includes halted, helpless narration, a mix of exclamations and broken-off rhetorical questions, atop different scenes of debris. One page is devoted to the body of a crab, panel borders separating the creature’s detached limbs; a later page includes a passer-by’s of shore-side litter. The impression is of resigned confusion, the narrator’s dual awareness of climate change’s effects and the struggle to process it completely.

Kimball Anderson’s contribution is the anthology’s final piece and one of the most outwardly mournful. It’s not the most arresting comic—at first glance, it looks like another wispy pencil piece—but Anderson establishes real powers of pacing and expressiveness. The comic includes halted, helpless narration, a mix of exclamations and broken-off rhetorical questions, atop different scenes of debris. One page is devoted to the body of a crab, panel borders separating the creature’s detached limbs; a later page includes a passer-by’s of shore-side litter. The impression is of resigned confusion, the narrator’s dual awareness of climate change’s effects and the struggle to process it completely.

Caitlin Skaalrud’s comic, which begins the book, is one of the few comics to depict an explicit future setting, and the only one to populate that setting. Skaalrud follows a pair of young hunter-scavenger types, and her free-verse captions refer to “a course for the brave”—a notion of life among devastation as a form of involuntary heroism. But there’s an ambivalence in the work too, no pure positive spin. Skaalrud’s palette is full of dingy, unpleasantly warm tones, and the piece conveys sweat, stink, and discomfort. It’s not an appealing vision, even if Skaalrud recognizes the dignity of her actors.

While Skaalrud’s piece allows for a measure of heroism, Oliver East focuses on complicity. His piece, “Hold Fast That Which Is Good,” layers hazy brick and copper tones underneath various scenes of industry—trucks, silos, construction equipment—and includes first-person rhyming verse atop the compositions. Warmer’s Kickstarter positioned the book as a collection of poetry comics; in practice, not all the pieces fit that definition. That’s neither good nor bad necessarily, but it’s bracing when East commits. He uses a fixed six-panel grid to complement his verse, conveying a worker’s despair about the larger system and his small role.

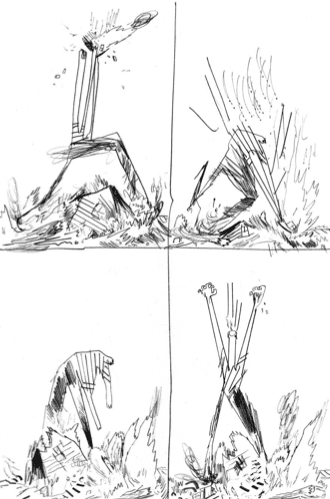

Missing in all of this is an expression of outright anger, so it’s a relief when Warren Craghead shows up. He begins with a figure shouting at a house aflame, the figure drawn in rough black scratches and dwarfing the house with its size. The figure proceeds to smash the house against the ground, and then smash what looks like a tree, before collapsing into a heap of debris. It’s a violent, self-defeating tantrum, rendered with terrific physicality. Warmer’s lack of other pieces like this is not strictly a deficiency—the anthology’s attention to more complex feelings is of course worthwhile—but the rage of Craghead’s is still essential.

Missing in all of this is an expression of outright anger, so it’s a relief when Warren Craghead shows up. He begins with a figure shouting at a house aflame, the figure drawn in rough black scratches and dwarfing the house with its size. The figure proceeds to smash the house against the ground, and then smash what looks like a tree, before collapsing into a heap of debris. It’s a violent, self-defeating tantrum, rendered with terrific physicality. Warmer’s lack of other pieces like this is not strictly a deficiency—the anthology’s attention to more complex feelings is of course worthwhile—but the rage of Craghead’s is still essential.

Other pieces in Warmer take still a different route. Two comics by separate pairings, Maggie Umber/Raighne Hogan and Alyssa Berg/Catalina Jaramillo, both work to aestheticize—and impart readers with—some ecological information. “pollination,” the Umber/Hogan comic, is an impressionistic watercolor look at the pollination process. It concludes with a page noting how global warming has disrupted this progress, a somewhat abrupt ending to an otherwise engaging piece. The Berg/Jaramillo comic, a piece of graphic journalism set in Chilean Patagonia, reads as too abrupt on the whole. The artists focus on a local scientist who has followed warming’s impact on the habitats and migration patterns of humpback whales. Their comic is not fully realized as either a piece of science reportage or as a character piece—interesting but perhaps a mismatch for the anthology’s format.

A comic by L Nichols midway through the volume sits between the more ecologically-minded pieces and the pieces about internal experiences. With a distinct gray-green palette and a loose, textured line, Nichols contrasts the lifespan of trees and the lifespan of humans, with trees drawn knotted and bent, totems of a world in disrepair. The piece struggles somewhat under Nichols’s lettering—present in such a childlike scrawl that it nearly infantilizes the piece—but the prose itself is moving. In lines like “Is the world changing too fast for them?”, Nichols combines a youthful personification of trees with a more adult awareness of the damages humans have caused them.

A comic by L Nichols midway through the volume sits between the more ecologically-minded pieces and the pieces about internal experiences. With a distinct gray-green palette and a loose, textured line, Nichols contrasts the lifespan of trees and the lifespan of humans, with trees drawn knotted and bent, totems of a world in disrepair. The piece struggles somewhat under Nichols’s lettering—present in such a childlike scrawl that it nearly infantilizes the piece—but the prose itself is moving. In lines like “Is the world changing too fast for them?”, Nichols combines a youthful personification of trees with a more adult awareness of the damages humans have caused them.

To some, the creation of hushed, poetic comics about climate change might seem a little decadent as long as the world is burning. But Warmer speaks for itself and makes a good case. The book reads like a product of conviction, particularly when its contributors succeed in putting a consciousness of climate change down on the page. The more people can recognize their internal experience of climate change in others, the less people will confront the future in confusion and isolation. Comics like these are a part of that process, small steps toward a more livable version of whatever comes next.