Sophie Yanow's autobiographical series In Situ reveals an artist whose understanding and experience of art, philosophy, politics and daily life are all inextricably bound together. Her new book, War Of Streets And Houses, is a fascinating study of protest, privilege, self-awareness and political frustration. It's an eyewitness account of being part of the tuition strike at a Montreal university in 2011 as well as a meditation on what it means to protest, both on a personal and global level. It's also a philosophical and historical examination of the history of counter-protest and counter-revolutionary actions on the part of governments. Indeed, the comic's title refers to an infamous pamphlet written by a French officer named Marshal Thomas Bugeaud, whose co-opting of houses in Algiers proved to be a key strategy in defeating separatists in the 1840s.

If there's a single unifying theme in the book, it's that of the ramifications of space. Yanow begins the book by talking about growing up near a forest, which gave her space to collect her thoughts, to reduce anxiety. Indeed, part of that anxiety was linked to being queer and in a small town, feeling the need to move to a bigger space. However, living in those cities didn't give her the same refuge from other kinds of anxiety. One could walk to certain parts of a city in order to try and regain that feeling (like in Paris, it meant going to the river or the wide boulevards), but "it's not the same as in the woods." That last phrase was drawn on a page where Yanow is sitting alone in the upper left hand corner of an otherwise blank page, a clever design solution in a book that's full of thoughtfully-considered design choices.

Space is also a consideration in terms of personal space at a rally, whether or not you will be arrested or beaten or "kettled" (penned in by police and then denied food, water and toileting for hours). The dichotomy between urban and rural is explored at length later in the book, when Yanow and friends leave Montreal to do some work on a farm, cheering them up but also causing Yanow to wryly stop and think "Wait how are we supposed to do the revolution out here." That sense of wanting to escape the conflict while feeling the pull to go back is in full effect here, especially as one friend says "I'm just not sure a bunch of privileged queers on a farm creates systematic change". Yanow doesn't disagree, but also notes that they needed the recharge to reemphasize their bonds.

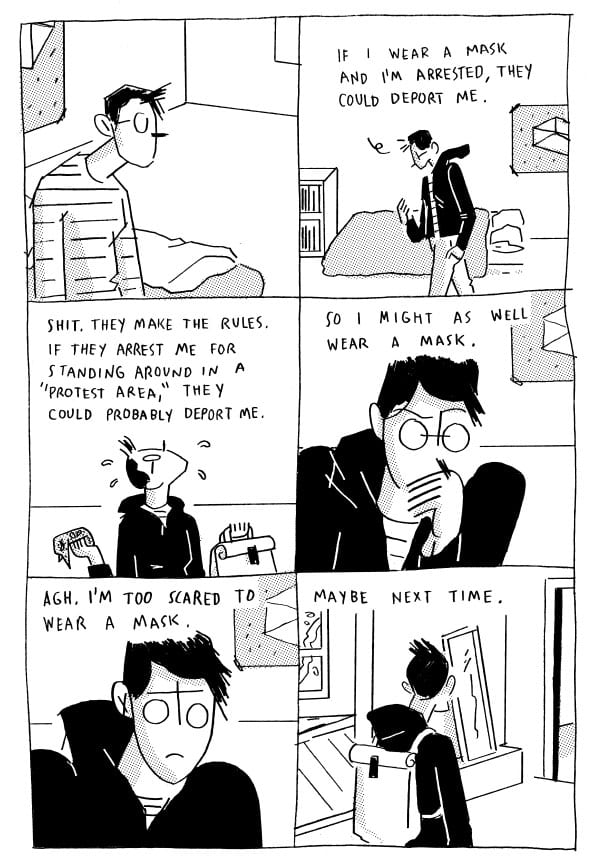

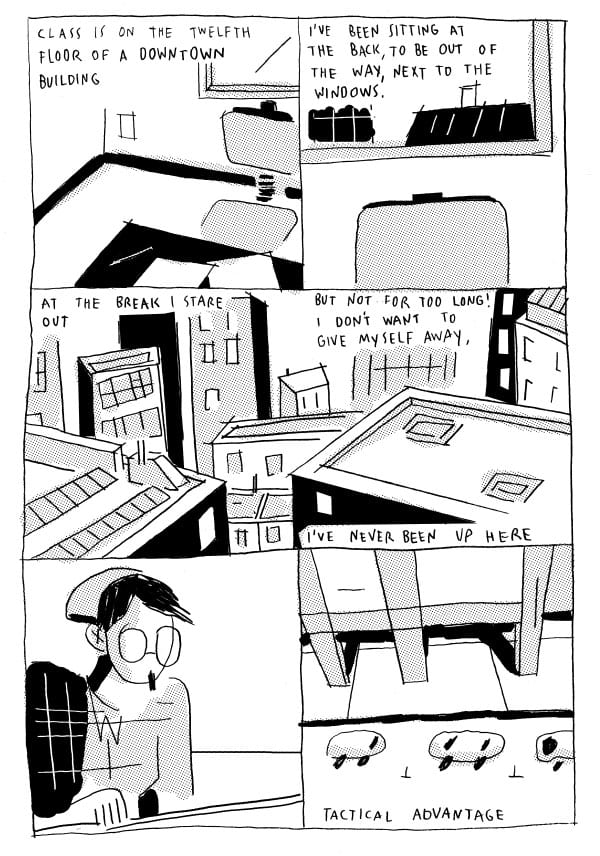

That sense of being an individual worrying about being arrested and the need to be part of something bigger than herself is a constant battle in this book. Even with that level of anxiety, Yanow realizes that she's lucky that she's white, as a friend of color notes that they worry about being arrested every day even when there's no protest on. She worries about being deported back to the US but doesn't let this stop her from joining the protests and even getting "kettled" by the police. This is all related somewhat dispassionately, as Yanow's emphasis isn't so much on her actions but on the bigger picture. She looks back on the protests and her small role in them as another historical event to be considered and studied, another small movement in resistance.

Of course, the most important examination of space goes back once again to the title and refers to public spaces. Algiers was such a difficult city to conquer because its layout didn't make much sense, the buildings were jammed tightly together and the streets were narrow. Much of this is covered in a fantastic two-page spread where Yanow quotes from Bugeaud, where a series of thin, horizontal panels contained the hints and outlines of buildings rendered in minimalist fashion, with some given texture by zip-a-tone effects. She really gets at the dizzying and disorienting nature of those streets and how Bugeaud saw them as something to demolish, and then later relates these theories to architectural planners who were hired to widen streets in Paris in order to prevent this kind of native resistance. This kind of urban planning that involves "widening the scale", making it easier to keep people apart.

Yanow's investigation into all of this is both personal and philosophical, because it gets at the essential question of "Who owns space (and spaces)?" Is it the state, private property owners, the individual, the collective or something else? Her critique here and in In Situ suggests that the state becomes uncomfortable when people start to use public spaces as a means of protest and strike. On the one hand, the fear of retribution, arrest and violence are enough to make one ask (to paraphrase the Rolling Stones) "What can a poor girl do?" For Yanow, the only thing she can do is try to continue and act according to her conscience politically while continuing to nourish herself personally with friends and other artists. As an artist and thinker, all she can do is document this as best she can.

Her rendering choices are a big key as to why the comic succeeds. She has the ability to flip from near-abstraction to a more naturalistic style, depending on the setting. Her figure drawings are exquisite: circles, lines and angles all whirling together and cohering on a panel-to-panel and page-to-page basis. The way she positions her head to indicate a sort of perpetually slumped-shoulder posture is one way she gets at gesture and body language with so much skill; despite the sketchiness of her line, one never feels cheated in terms of visual impact. Indeed, the abstractness of her line combined with the artificial solidity of the zip-a-tone gives the protest scenes a strange quality that would be difficult to capture in a more naturalistic style. It's as though the adrenaline and fear she experienced rendered the experience no more than a set of rushing lines. It's sort of a flip-side to Joe Sacco's slightly cartoony naturalism in capturing an environment; indeed, with her pupils blotted out by the white circles of her glasses much like Sacco, they are not dissimilar both in terms of intent and execution. The difference is that Yanow is not a temporary visitor, but someone who chose to live and work in Montreal. The stakes are different and certainly higher, and she gives the reader a carefully nuanced account of these stakes in a manner the eschews fiery polemic and instead embraces personal relationships and philosophical study.