Ulli Lust’s North American debut, Today Is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life, was a harrowing, heartbreaking and incredibly powerful work. Her 2013 graphic novel, Voices in the Dark, released recently in the U.S. by New York Review Comics, strives to be just as ambitious and emotionally wrenching. It unfortunately isn’t, but it's not for lack of trying, and it does prove that Lust is more than a flash-in-the-pan cartoonist.

An adaptation of a novel by German author Marcel Beyer, Voices in the Dark tells the story of two people during the second world war: Helga Goebbels, the eldest daughter of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, and Hermann Karnau, a fictional sound engineer who ends up working for the Nazis and finds himself in the Führerbunker, alongside Helga and her siblings, during the final days of the Third Reich.

One of the biggest problems with Voices lies in the character of Karnau. I have no problem with an unsympathetic or unlikeable protagonist, but Karnau is: a) clearly designed to be a surrogate for the reader; b) really boring.

Obsessed with recording, cataloging, and describing virtually every human utterance, non-verbal or otherwise, to the point of tedium, Karnau expounds upon his passion for pages without sufficiently transferring said passion to the reader. When at one point Karnau comes to grips with the fact that there are sounds that will forever be beyond the reach of his ears, my reaction was not “how sad for him” but “who cares?” (Insert your own comment about the “banality of evil” here.)

The opposite problem lies with Helga and the rest of the Goebbels children. Helga is presented as an intelligent, compassionate child -- clever enough to tell that things aren’t going well and that the adults around her are lying. And there are hints that, if she were to truly know what her father and his beloved Führer have done, she would recoil in horror. In one visually stunning sequence, Helga gets severe claustrophobia listening to her father rant to a packed theater, the rush of faces, bodies, hands and shouting swirling together into abstract shapes.

Helga’s sense of distrust and unease, combined with her love for her siblings (along with her general innocence) makes her an extremely sympathetic victim, given her eventual fate. But there are times when she seems too idealized and reading the book, I couldn’t help but wonder: What if she had loved her father’s speech? What if one of her siblings (who are mostly devoid of personality) was ardently pro-Nazi? The only time we see any negative behavior from Helga and the kids is when they play a nasty game titled “brownshirts and undesirable elements," and even then Helga is shocked into shame by her behavior. I felt as though there needed to be someone to push against her naiveté, and Kranau is too removed a figure to do so.

The relationship between Helga and Karnau is obviously a key facet of the story, but Voices depicts very few interactions between the two. It isn’t until the final third of the book that they are together in the bunker. Up till that time they are mostly living separate lives, with only occasional brief encounters. Thus, it’s hard to understand Karnau’s eventual affinity for the children, especially given how someone so antiseptic and indifferent he is to the world around him. When sent to the battlefield, he appears to have little regard for the fate of his fellow soldiers. And later on he takes part in barbaric experiments and surgical procedures to remove or alter the larynx of various "undesirables." How someone so indifferent to others’ suffering can express warmth towards the Goebbels children is not something Lust ever examines closely.

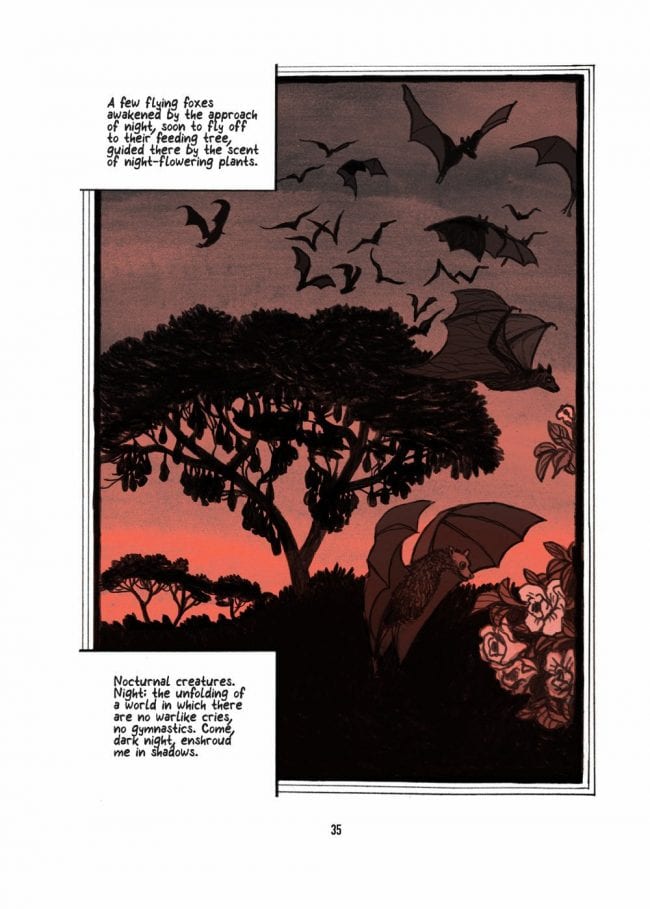

Despite these problems, Voices in the Dark is still worth reading if for no other reason than to appreciate Lust’s considerable artistic talents. Whereas Today Is the Last Day proffered a stripped-down, sketchbook approach, Voices is suffused with expressionist montages and color – washed-out browns, blues and pinks. When Lust verges into more abstract or surreal imagery, the book really takes off. At one point in the afore-mentioned sequence of the kids playing “brownshirts,” Helga and her one sister become huge, monstrous mouths screaming orders. A late sequence at a farewell party of sorts devolves into cacophony, which Lust delineates as lightning strikes, onomatopoeia and swaths of black, slashing lines.

But these sequences, stellar or not, never add up to a whole, in large part due to the flawed portrayal of Karnau and the idealized portrait of Helga. Voices in the Dark is daring in concept and execution, and proves that Lust is an artist to be reckoned with, but feels cold and distant and fails to engage the reader as fully as her previous book did. I still look forward to her next book.