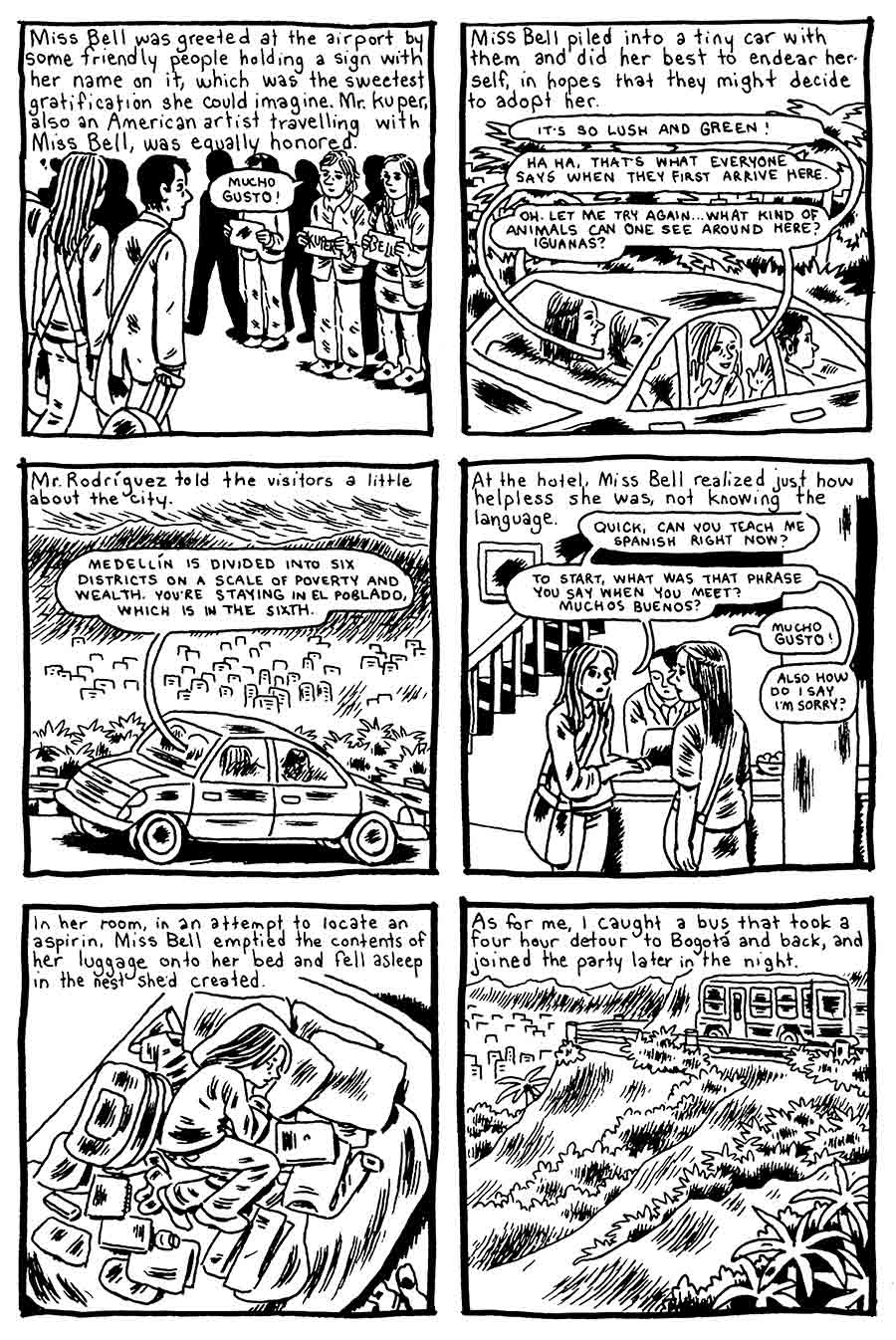

Poor Gabrielle Bell. You’d think a cartoonist’s life would be perfect for her loner tendencies, but she’s constantly having to deal with being flown to comics events around the world and facing expectations to interact with the community that comes with cartooning. She doesn’t always do so well. Turns out it’s very challenging to be a creative person and an introvert, because the most basic reality is that you have to interact with people to have fodder for your diary comics. Also, any given interaction will give you an opportunity to say something awkward.

That’s not to make fun of Bell, not at all. For an industry with so many introverts, Bell’s personal experience is probably recognizable to many contemporaries as similar to their own. In capturing the day-to-day incidents of her existence, the diaries present a constant personal struggle against interacting with humans, versus fantasies that focus on leaving community behind and embracing isolation. You have to wonder if Bell is as socially awkward in real life as she presents herself in the comics or if her cartoon monologues play up an aspect of herself for comedic effect.

In her introduction, Bell discusses the implications that presenting personal writing in public have on your life. Your daily experience can begin to include a meta dimension that folds in an invisible audience. At the same time, an introvert like Bell can explain her introversion in a outgoing way that she could probably not achieve in her real life. What you end up with is a conundrum of experience that may or not be what actually happened, but is how Bell, on the inside, experienced them, a kind of running dialogue in her head, portions of which may make it to the sketchbook.

Life is the clutter that we edit down in retrospect, trying to create a cohesion that is representative of the self that is much harder to make publicly plain in real time.

Bell’s encounter with Dominique Goblet at Fumetto-Internationales Comix Festival in Switzerland gives insight to what Bell sees beneath the surface of her autobiographical work. Through lectures and conversations, Goblet unveils an autobiographical goal for Bell, an understanding that “there is no trueness,” in Goblet’s words, “just facts and the links that connect the facts.”

It gets to the heart of what Bell has done naturally in her autobiographical work before and strives to do more purposefully as she continues. Why does she challenge herself to these diaries when she also often mentions how dissatisfied she is by the prospect of doing them? What is she trying to attain by sharing these works that could easily function as private, daily exercises in cartooning of no interest to anyone else but the cartoonist? Is this part of Bell’s pursuit of a phantom called objective truth? Or is it her acknowledgement that we fashion our own truth, and her way of doing so is within panels on paper?

It’s the eventual appearance of boyfriend Steve that suggests autobiography is no more pure in its expression of reality than fiction. Steve’s monologue points directly to the idea that it’s all the result of editing, and what isn’t included in the narrative is as telling as what is there plainly in front of you. In this case, it’s Bell’s presentation of herself as unattached. Not that she ever says she is unattached, but she fails to mention a boyfriend, and that completely changes the reality she presents, until she chooses to capture a conversation that has Steve questioning her presentation.

It’s the eventual appearance of boyfriend Steve that suggests autobiography is no more pure in its expression of reality than fiction. Steve’s monologue points directly to the idea that it’s all the result of editing, and what isn’t included in the narrative is as telling as what is there plainly in front of you. In this case, it’s Bell’s presentation of herself as unattached. Not that she ever says she is unattached, but she fails to mention a boyfriend, and that completely changes the reality she presents, until she chooses to capture a conversation that has Steve questioning her presentation.

Bell plays with the line between fiction and autobiography by injecting moments of total fantasy that may well comment on reality better than any actual real moments. These mostly involve encounters with bears and zombie apocalypses, as well as one hilarious segment where she speculates recovering lost memories as revelations to other lives, and fold in psychological truths that might never appear in the work otherwise. The diary ends with an entire section written by a third person, a fictional secretary that Bell has hired to deal with her diary for her. With this, Bell completely crosses over to full fictional character, both herself and her own biographer, bringing so many of her concerns full circle and in a format that transforms her self-deprecation into the insulting perception of someone else, who may or may not be Gabrielle Bell.

Bell plays with the line between fiction and autobiography by injecting moments of total fantasy that may well comment on reality better than any actual real moments. These mostly involve encounters with bears and zombie apocalypses, as well as one hilarious segment where she speculates recovering lost memories as revelations to other lives, and fold in psychological truths that might never appear in the work otherwise. The diary ends with an entire section written by a third person, a fictional secretary that Bell has hired to deal with her diary for her. With this, Bell completely crosses over to full fictional character, both herself and her own biographer, bringing so many of her concerns full circle and in a format that transforms her self-deprecation into the insulting perception of someone else, who may or may not be Gabrielle Bell.

All this might come off as very theoretical and vague in some hands, but Bell never drags out the point and sticks instead to just being amusing and injecting some of these ideas as she goes along. As a collection of slices from a cartoonist’s life - including cameos by virtually anyone who is anyone in indie comics - Bell is personable and funny and there is no requirement to go further in order to enjoy her work. But the pleasure of Bell is that there’s so much that lies further if you want to delve beyond the amusing awkward conversations.