I've read Mike Dawson's Boy Scout slice-of-life drama Troop 142 in many incarnations: as a webcomic, as a minicomic, and finally as a handsomely-designed paperback released by Secret Acres. This final iteration of the comic is the definitive version and contains some subtle changes that lend the book a greater air of restraint and ambiguity. What I like most about this comic is that Dawson gives every character a layer of complexity that belies one's initial impressions of them. There is no single character the reader is asked to identify with, as even the nastiest of characters show the capacity for empathy and the most milquetoast of characters show the capacity to abuse power. This is a story about the tension between the ideals of being a Boy Scout (Dawson twice portrays the Boy Scout Oath being recited, to emphasize this disconnect) and the Darwinian realities of a group of boys living at a camp for a week. The quasi-military nature of the Scouts, which is dependent on ritual, tradition and hierarchy, only serves to feed the ensuing power struggle as individual boys struggle to maintain and advance their pecking order on the social ladder.

Dawson is a former Scout who has noted that most of his feelings about his experiences in the BSA are positive. The details of this book reflect an insider's experiences, right down to specific activities and unofficial traditions, like the Scout who showers least getting the "grunge sponge" award, and buckets full of dirty water, at the end of the week. What makes the book work is Dawson's remarkable facility for writing dialogue with a painful level of verisimilitude in how it depicts the kind of crude conversations and concerns that teenage boys have. Setting it in the mid-'90s (contemporary to his own experience) removes more modern distractions like cell phones and laptop computers, but also puts front and center an aspect of the culture wars of that era: the controversy regarding gay Scoutmasters. If there's one character in the book about whom the reader is meant to feel little ambiguity, it's the squatly designed Big Bear, the elderly scoutmaster on the lookout for moral turpitude who proclaims to all that as far as he's concerned, gays will never be allowed in the Scouts.

Wisely, Dawson avoids attaching a melodramatic plot or contrived action scenes to the proceedings, even if he makes the occasional feint in that direction. The real drama is in the relationships depicted in the story, accentuated by Dawson's cartoony line that allows for expressionistic flourishes in a naturalistic setting. The emotional core of the story surrounds the trio of Matt, Jason, and Tony as they jovially cut each other down, probing for weaknesses in the way that only close friends can. Tony is the athletic alpha male of the group, dictating their activities, including who gets the LSD he brought on the outing. Dawson is wise to treat their later acid trip in a matter-of-fact way, even playing it for laughs to an extent, rather than make it the dramatic crux of a plot-point. The push-and-pull of their relationship comes to a head when Tony thinks Jason has stolen his extra hit of LSD, leading to an escalation of words that winds up getting physical. Vulnerability, empathy, and kindness are sometimes undervalued or denigrated at that age, but one of the central points that Dawson emphasizes is that this is simply a reflection of typical adult masculine attitudes. Even the father of Jason and his younger brother David, Alan, who seems to be the liberal hero, is later revealed to have no idea how to relate to other men and devolves into using force against one of the boys.

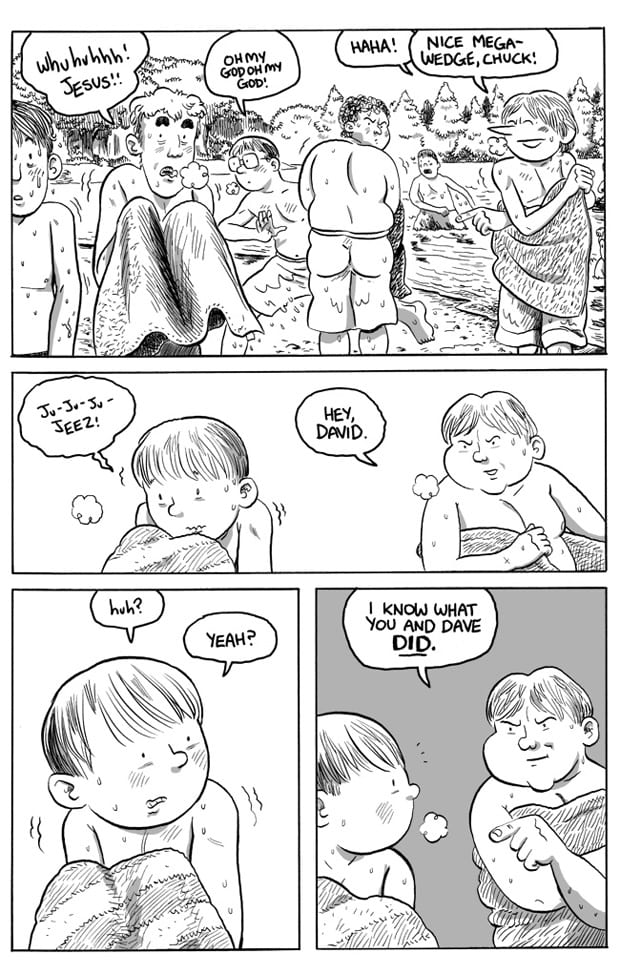

The flipside of that experience is that of the burgeoning attraction between David and another boy named David. Without explicitly revealing what's happening between the two of them (and what is very common for teenage boys, especially in that setting), Dawson makes it clear that they are experimenting with each other sexually, setting up the experience by talking about girls giving blowjobs and receiving oral sex from someone you're not necessarily attracted to. More interesting is the way they avoid identifying this as something gay (one David is quite unnerved when someone refers to the other David as his "boyfriend"). One of the Davids sabotages the tent of the camp scapegoat Chuck so that it reads "fag" when it rains, soaking his stuff. He gets tossed out of the camp, but the other David engages Chuck in a fight later in the book, once again tossing homophobic slurs at the least-liked boy in the camp as a way of deflecting identification with something that is openly mocked not just by his age group, but openly condemned by authority figures.

Chuck is the sort of quiet loner who gets chosen as a target for abuse for no good reason, as even one of his tormentors admits. When asked why he hates someone in his own troop so much, Jason cheerfully says, "I don't know. We just do!" Chuck is defensive and fractious, with no sense of humor about himself. That may well be because of his status as the son of a conservative, hard-ass scoutmaster named Bill who embodies the potential for hypocrisy, since he’s a bully who uses his status as an authority figure to push around the kids. It’s clear that Bill has no idea how to communicate with his son, as the scene where he intentionally scares him (with a truly creepily-drawn mask) indicates. He hasn’t moved much beyond the ways in which a teenager might try to indicate closeness: through insults and pranks. Even Bill emerges as a complex figure when he genuinely sympathizes with Jason, who has failed a grueling merit badge test, but it's still obvious that he has no idea how to reach his own son.

Dawson's cartoony flourishes, such as a nose so pointy on one kid that it looks like a long letter "v" protruding from his face, are a visual highlight of the book. Some kids have a certain lumpiness to them, while others have pronounced facial features, such as impossibly bushy eyebrows. “Blue collar” Bill has a big forehead (with a slight, Cro-Magnon bulge) and a Dan DeCarlo-esque nose. The cartoony nature of Dawson’s line is what allows him to quickly differentiate the large cast of characters: a looped chin here, an exaggerated set of eyebrows there, and lots of unkempt hair. Dawson uses a thin line and a minimum of shading, hatching, and extensively spotted blacks. Visually, the key to this comic’s success is his ability to convey body language, gesture and character interaction, especially since subtext is such an important part of what’s occurring in the narrative.

Dawson edited out some of the more overt political discussion from the earlier webcomics, stuff that made a debate about Scouts not allowing atheists and Bill condemning Bill Clinton seem artificial, stilted, and didactic. Creating greater ambiguity in his characters while putting the focus on character interaction was a smart way to go, rather than work out a culture-wars debate that may have been in the author's head by way of his characters. The result is a comic that's not about the monstrous nature of adolescence or even the less pleasant truths about masculinity in particular, but rather one that focuses on the fragility of ego, the demands of social and cultural mores, and the ways in which we all fear humiliation and vulnerability.