Tadao Tsuge debuted as a cartoonist in 1959, a couple of years after he began work at one of the for-profit blood banks in postwar Tokyo. He would keep the blood bank job for most of the 1960s, long after his first appearance in Japanese comics anthologies. In that decade, he also began to create the stories that appear in Trash Market, glimpses of daily life in the city’s impoverished neighborhoods. A modest cult emerged around the comics—“If Tadao’s readers are few by Japanese standards, his supporters are wholly committed,” notes the book’s editor and translator Ryan Holmberg—leading eventually to this English-language collection (and hopefully not the last volume of Tsuge’s work to reach the US and Canada). Throughout the stories, Tokyo residents—students, hustlers, veterans—argue, make plans, and frequently avoid saying everything they have to say. Tsuge’s comics are often dialogue-driven, and usually dialectic too, charged by tension and contradiction on page after page.

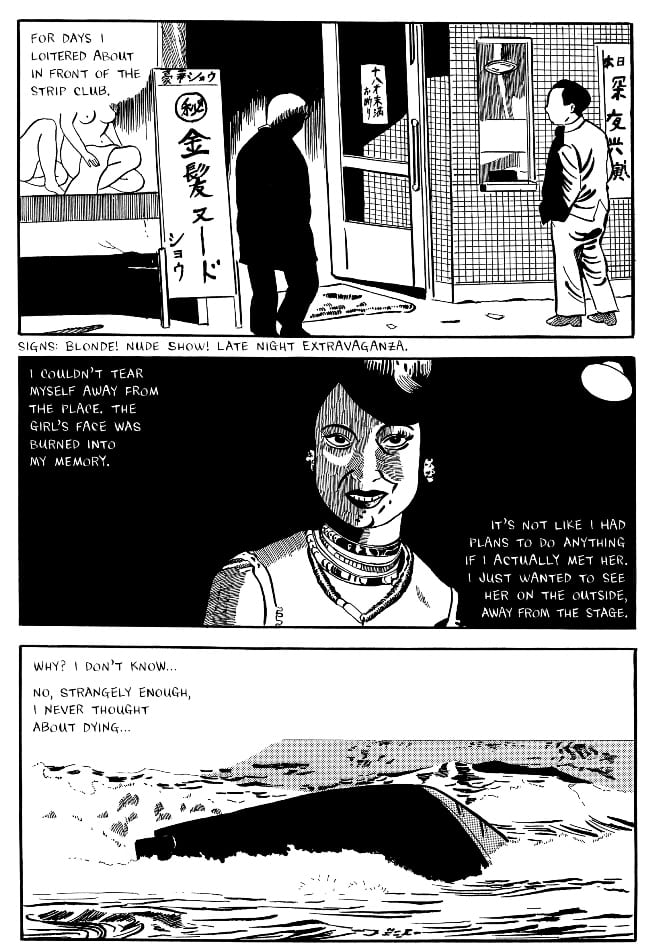

Although Tsuge depicts grim, even squalid conditions throughout Trash Market, a strange buoyancy moves through most comics in the collection. “Manhunt,” for instance, comes on like a dream, opening with spreads that feature silhouettes, cryptic captions, and scenery that’s scattered across different moments in time. The story concerns the wanderings of a middle-aged bureaucrat, disenfranchised and struggling with an unreliable memory. Tsuge’s compositions meet the character on his own terms, presenting figures that are partially obscured or that exist as pure outlines, as well as abstracting familiar landscape elements until they read like visual non-sequiturs. “Manhunt” never loses interest in the plight of its central character—nor does it suggest a hopeful resolution—but Tsuge’s work flows as if liberated by resignation to the status quo.

The collection’s first story, also fairly grim, likewise includes scenes that stand out for their visual airiness. One page, documenting the evening walk of an outsider artist, finds the character almost floating across a series of hills and embankments. On another, the artist recounts the moment in which his object of fascination, Vincent Van Gogh, severed one ear. Tsuge stages the sequence in a disorienting fashion, with Van Gogh drawn as an anatomical knot against blank backgrounds. Whatever the scene is, it’s not a work of simple naturalism—the panels encourage a sense of mystery while the narrator relates a straightforward starving-artist story. In the opener, as with “Manhunt,” a powerful tension emerges between Tsuge’s subject matter and the effects he creates on the page.

Images like those from Trash Market’s Van Gogh sequence suggest both the deliberate intent of a careful storyteller and the efforts of Tsuge to draw within his limitations. They are not the only panels that feature a freewheeling approach to the human form. But elsewhere, as with the Van Gogh sequence, this approach often works in a story’s favor. “A Tale of Absolute and Utter Nonsense” is a pitch-black protest farce. A group of violent student radicals confronts a group of riot police, with many members of both parties killed or maimed in the process. Some of the students achieve a kind of transcendence through brutality—Have you ever felt so great?, one says—and yet the sentiment lands like a punch line. Even if “Utter Nonsense” weren’t in the story’s title, the linework would still invite ambivalence. Tsuge’s line is capable enough to make each stabbing or crack of the baton legible, but loose enough to make the entire affair look ridiculous.

This story, by the way, also highlights another of the collection’s tensions. Before the radicals of “Utter Nonsense” form a united front, Tsuge shares a dialogue between those who have opted out of the political mainstream and those who have dismissed the possibilities of politics entirely. Though “Utter Nonsense” suggests that, in time, they all go SPLAT. Tsuge self-identifies as apolitical and applies the same label to his work, but Trash Market’s stories still benefit from a steady curiosity about students who would draft manifestos or working poor who would attempt to organize.

The book’s back matter, which has short pieces of prose autobiography by Tsuge and an overview of the cartoonist’s work by Ryan Holmberg, further illuminates scenes like the beginning of “Utter Nonsense.” The closing essays note that Tsuge lived among these more politicized workers and students, and the comics themselves are more remarkable for that fact. Tsuge became a comics anthropologist of his peers, even as he continued to slog through jobs on the margins himself. The stories Holmberg has collected for Trash Market are thoroughly unsentimental, and any decent consideration of Tsuge’s comics ought to steer clear of too much sentimental language. But it is no exaggeration to say that the book is a triumph—a moving collection of art made in depressed circumstances, and with irony and ambiguity intact.