To Get Her is a lively and clearly very personal comic by Bernie Mireault, a cartoonist whose work I have admired for almost twenty-five years. It's also, narratively, a ringing disappointment.

I learned about To Get Her from Tom Spurgeon's May 6 interview with Mireault. I understood from that interview that the book's current incarnation, its only public incarnation thus far, is that of an extremely limited edition, partly Xeric-funded (though Mireault hopes to republish it for a wider readership). So I was startled to find a copy locally.

To Get Her has reportedly been in the works since 2003. My own knowledge of Mireault dates to his collaboration with Matt Wagner and Joe Matt on Comico's Grendel, way back in 1987 (an arc later collected as The Devil Inside). That collaboration put Mireault on my radar, and so I dug into his quirky, low-rent superhero pastiche The Jam, a generally lighthearted riff on the genre but laced with semi-autobiographical, underground-flavored elements. The Jam began as a backup serial in the Canadian series New Triumph back in the early mid-80s, then began to find its own way after 1987 (Comico published a one-shot after the Grendel run that I glommed onto very happily). By the mid-90s I thought of The Jam as a humorous but soulful alternative to superheroes-as-usual, a project that, despite its fitfulness and its caroming between publishers, promised what Mike Allred's Madman also seemed to promise at the time: life, energy, and homespun storytelling within the straits of that oh-so-familiar genre. I dug it the way I dug Allred's work, and Mike Gilbert's work on Mr. Monster, and the way I still dig Paul Grist's myriad superhero comics.

Over the years I've tried to follow Mireault's comics work and have sometimes failed, as the several iterations of The Jam (Matrix, Comico, Slave Labor, Tundra, Dark Horse, Caliber) confused me or gave way to shorter efforts that, for me, didn't quite jell—for example the Dr. Robot comics that appeared in the back pages of the Dark Horse version of Madman in 1999. Every one of those strips was a buoyant formal workout, showing Mireault's command of cartooning, design, and color, but the concepts seemed over-familiar, shopworn, as if Mireault had abandoned The Jam as a vehicle but hadn't yet arrived at anything else. Of course he was busy living, and doing other things I knew nothing about. To Get Her must have been one of those.

It turns out Mireault hasn't abandoned The Jam, but has transformed its hero, Gordon Kirby, alias The Jammer, into To Get Her's semi-autobiographical protagonist. This version of Gordon Kirby makes clear that Gordie is Mireault's surrogate. He's now very much a down-on-his-luck cartoonist who not only lives the life of the Jammer but also chronicles it on the comics page.

In other words, the central conceit of To Get Her is that The Jam is Gordon Kirby's autobio comic—which is why the book climaxes by bringing us right to the threshold of that first Jam story from New Triumph, back in 1984.

Obviously this Gordie stands in for Mireault. To Get Her goes beyond providing a backstory for The Jam, recounting the disintegration of a long-term relationship in painfully confessional terms that inevitably seem autobiographical. It also experiments with mixed genres, or at least mixed means of expression, fusing comics with pages of ruminative typeset text—and incorporating a number of Mireault's own comics, here imagined as Gordie's. It even includes as a jam page by Mireault and several real-life cartooning buddies—one of many moves that serve to blur the lines of memoir and fiction, making To Get Her a shifty autofiction rather like, say, Seth's It's a Good Life, If You Don't Weaken.

Unfortunately, it doesn't work. I mean, it really doesn't work. I want to like the book desperately, because I'm a longtime Mireault reader primed to like what he does. I'm a fan. But To Get Her tries to salvage too much of The Jam's gnarled continuity, and as it does so it undercuts the power of its ruminations with daft subplots and narrative feints and quick-fixes that clash with its bitter autobiographical insights. Tangled plotlines from past Jam stories—a missing person, a police investigation, and so on—are brought forward just when Mireault seems to be trying to sail past all that. A comically broad subplot puts paid to the book's ostensible focus: the painful disintegration of the relationship between Gordie and his partner Janet.

That relationship, I recall, used to be a sweet selling point of the Jam comics, I suppose in the same way that Frank's relationship with his girlfriend Joe works in Allred's Madman, or, more to the point maybe, the way the bond between Billy and Jane works in Dean Haspiel's semi-autobio but super-wild Billy Dogma comics. Like those other cartoonists, Mireault seemed to be doing a fantasy autobiography rooted in romance. To Get Her questions and undermines all that romance in favor of pained self-examination and, ultimately, loss. The relationship between Janet and Gordie is stripped of its sugar and becomes the book's central problem, one that is set forth in the book's opening salvo of bitter reflection: several pages of loosely edited and highly abstracted prose, thickened by verbal roadblocks like these:

A superfluity of effort coming from both sides would make light work indeed of the unglamorous tasks that are usually passed, hot potato style, to the lowest person on the totem pole. To have the comfort and security of being part of a fairly run and functional team, this is what I want for everyone. Especially for myself and my partner. (6-7)

Some of these lines manage keen insight into what makes relationships work and what makes them difficult. Mostly, though, the prose is gaseous and rather bland.

To say that To Get Her is at odds with itself is an understatement. It's easy enough to say that Mireault's trademark winsomeness and joy have been sidelined by bitter personal experience: this is his divorce album, so to speak. I would like to say that the book's difficulties make for a thorny but not wholly uninteresting new approach, something worldly-wise, hard-won, tougher, a bit trickier to read perhaps, but intriguing. And all of that is true. But just when I find myself warming to the idea of darkly reflective autobio from Mireault, To Get Her goes off the rails, tucking in more of the old Jam stuff than this sober new approach will let fit, and in the process showing up, by awkward contrast, the slightness of the old comics' charms, that is, revealing just how feather-light, delicate, and evanescent the thrill of those old Jams was. This move doesn't make the old work look good, yet it doesn't liberate Mireault to pursue a genuinely new direction either.

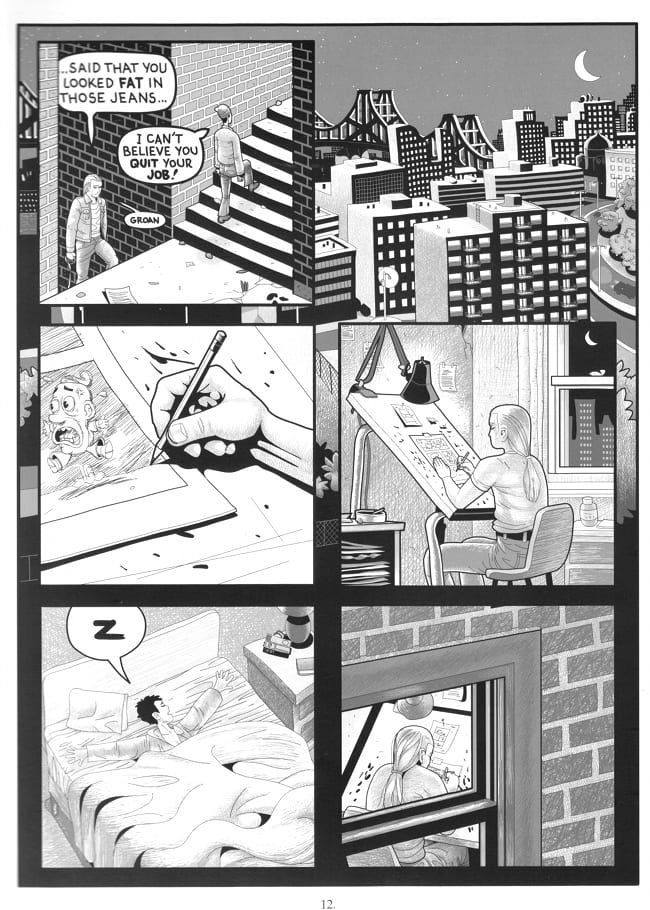

The relative sobriety of the book is enlivened by several wonderful feats of cartooning, and, visually, Mireault's energy persists even in the face of some debilitating moves in the direction of digital aridity. I miss the old, hand-rendered scratch of the early Jams, which here has largely been replaced by a digitized clear-line aesthetic and somber gray tones; however, I do see some wonderful page-building and cartooning here,

and Mireault keeps tossing in different examples of his other work to stir things up. He really is a wonderfully skilled and loving comics artist, clearly enthralled by the medium. He is not, however, a first-rate writer of people, and that hobbles him sorely here.

Mireault clearly sees the book as a meditation on the relationship between love and work, hence its repeated use of two paired icons, the heart and the wrench (first shown on the cover). That relationship feels contested and difficult here, as I suspect he intends. Indeed the book's plot seems to build toward the end of Gordie and Janet's relationship, which imparts a feeling of fatalism and slow inexorability. What I came to expect through my reading was a frank appraisal of how a once-romantic, now half-broken, love must end. However, To Get Her ultimately fudges this by leaning hard on a farcical subplot about one of Janet's suitors, an absurd, posturing clown with a convenient mental problem who kicks the story in a different direction. Broad strokes finish off this plot even as Mireault ushers Janet out of the picture, so to speak, for the final break,

which is delivered over the phone in a Chris Ware-like sequence of flattened affect and dull repetition—the kind of thing that Ware can do brilliantly but that comes off here like a cheat. There's no sense of mutual recognition or emotional culmination in this. Furthermore, a deus ex machina gift of cash to Gordie—a dividend from that wacky subplot—belies the story's truths about the travails of the working-class cartoonist. In short, Mireault's move toward soul-searching semi-autobio gets scotched by plot devices of a tacked-on, unearned, and unpersuasive kind.

Tonally, To Get Her is an unstable concoction. It's a careening, uncertain, disunified mess, a series of nervy bank shots that don't come off. Mireault strikes me as a cartoonist who prefers to work in a bright, positive register, but who, in this case, has something dark he needs to get off his chest, something he needs to process in order to establish a new beachhead for his work. Unfortunately, the result has a forced, unhappy quality. In fact, for such an ambitious, long-simmering project, and such a potentially important one for the author, it seems surprisingly ill-judged and premature. Despite some attempts to humanize Janet—i.e., to do justice to both sides of the story's central relationship—in the end the book seems like an awkward if not spiteful act of self-justification.

I can't bring myself to dislike To Get Her exactly. It boasts some wonderful evocations of place and mood, quite a few pages of nicely elastic cartooning, and several fascinating formalist coups. But, it must be admitted, the book finally fumbles its insights and falls to pieces in a bemusing and disheartening way.

Mireault continues to be an ace cartoonist without a sturdy vehicle. That's too bad. To Get Her seems less like the opening of a new chapter and more like, already, a memento of a hard time.