The opening issue of the five-issue miniseries Thumbs, by Sean Lewis and artist Hayden Sherman, mainly focuses on a sister taking her wounded brother to the hospital for medical care. The press release for the book mentions Charlier Brooker and Annabelle Jones' Black Mirror, our current moment’s most relevant science-fiction concern. Brooker has always in his writing shown a true distrust of human selfishness, working in the territory scratched out by Rod Serling and George Romero--it's a world view where people poison their own well, where we are the monsters. It's a place where it doesn’t matter what the hook is, because you have to be more worried about your neighbor with the gun than any monster that is breaking down the door.

Thumbs seems to come from a different school, one which the creators may not even be aware of, the post-cyberpunk of the '90s, things like Bruce Sterling’s Holy Fire and Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age, what you could call pre-9/11 tech anxiety books. In them, there are the kids who have been left behind by a technologically advanced society, the omnipresent tech du jour (a character is very clearly meant to be Elon Musk), adults that are often bad or missing, and a half-useful slang that’s only there to patch over uninteresting character motivations. Thumb's creators don’t need to have read those books as there's a type of science fiction that seems self-generating. The kind where it’s too clever by half, and could come from video games or YA novels or anime. The kind where the world falls apart if you tug at the ideas just a little. A book like Jennifer Egan’s Welcome to the Goon Squad can exist where it hits dozens of cliches and you feel like it’s not on purpose, but because the author literally has never read or watched any science fiction.

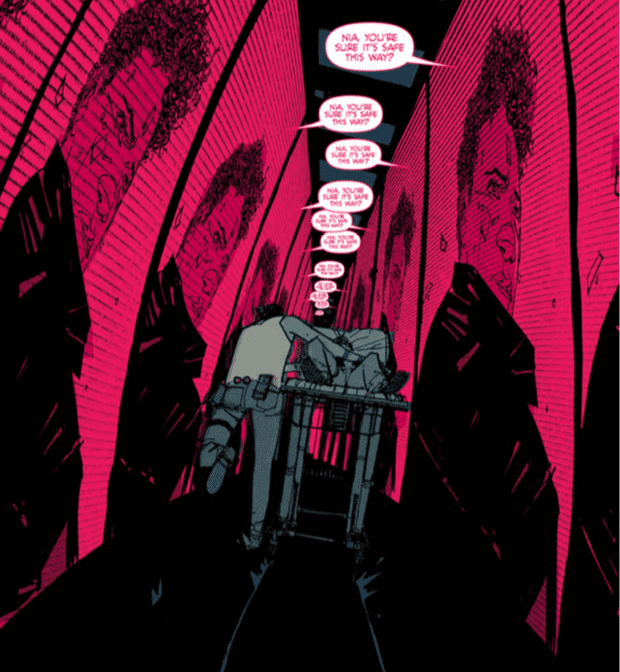

Thumbs is the version of these things where children are raised by a free omnipresent tech and volunteer for some unspecified army in order to gain prominence in a society that’s abandoned them. The dialog is heavily expository. The art is mostly here to convey motion to a dialog driven piece (the press release also tells us that the writer is a playwright so… that explains it). The coloring is monochromatic, hitting a certain tone of pink against grays to show the intrusion of this technology on the poor and mostly unprepared world it’s blindsided. “Glass time” is mentioned a lot, which reminded me of the bad parts of Egan’s novel.

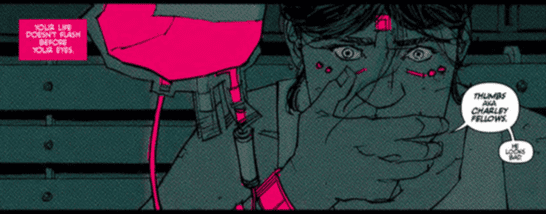

We learn about our characters’ childhoods -- they grew up brother and sister in a trailer park in the woods, tres chic -- and then the issue ends on the traditional “unconscious male wakes up abandoned after massacre” scene. The female lead is missing, obviously setting up the shifting perspectives of these two characters over the course of the series. The kids weren’t raised by their parents, who work ("POOR PEOPLE HAVE TO WORK" — two pages are dedicated to discussing this as if it were some cyberpunk August Wilson), so they were raised by a computer program. They frequently play violent, first-person-shooter-esque games that they are then rewarded for in their real lives. This is meant to highlight how we socialize the children of the poor, how video games long ago shifted from entertainment to task-based training tools. It is also a thirty-year-old idea, with so much shine taken off… you can’t call this chrome anymore. You can’t call this speculative. It’s just dressed up. I don’t know what the conflict is… or more honestly, I don’t care about what conflicts are presented. That cheap/free tech may be as oppressive and damaging as the kind that boxes the poor out and makes them pay three dollars to print their resume at the library. The big reveal is that a young person wakes up as an old, I assume to further explore the dislocation millennials feel now that there is a world in which they can never fully find good footing.

We learn about our characters’ childhoods -- they grew up brother and sister in a trailer park in the woods, tres chic -- and then the issue ends on the traditional “unconscious male wakes up abandoned after massacre” scene. The female lead is missing, obviously setting up the shifting perspectives of these two characters over the course of the series. The kids weren’t raised by their parents, who work ("POOR PEOPLE HAVE TO WORK" — two pages are dedicated to discussing this as if it were some cyberpunk August Wilson), so they were raised by a computer program. They frequently play violent, first-person-shooter-esque games that they are then rewarded for in their real lives. This is meant to highlight how we socialize the children of the poor, how video games long ago shifted from entertainment to task-based training tools. It is also a thirty-year-old idea, with so much shine taken off… you can’t call this chrome anymore. You can’t call this speculative. It’s just dressed up. I don’t know what the conflict is… or more honestly, I don’t care about what conflicts are presented. That cheap/free tech may be as oppressive and damaging as the kind that boxes the poor out and makes them pay three dollars to print their resume at the library. The big reveal is that a young person wakes up as an old, I assume to further explore the dislocation millennials feel now that there is a world in which they can never fully find good footing.

It’s trite.

It’s why people don’t like plays. Watch the Rhine didn’t exactly age well, and Lillian Hellman had (and HAS) a whole lot to say about the roots of fascism growing in the states as the nazis take power in Germany. But art ages because what was once subtle is now shouting. There’s a lot of symbolism and extrapolation here. There is very little imagination or insight.

It’s why people don’t like plays. Watch the Rhine didn’t exactly age well, and Lillian Hellman had (and HAS) a whole lot to say about the roots of fascism growing in the states as the nazis take power in Germany. But art ages because what was once subtle is now shouting. There’s a lot of symbolism and extrapolation here. There is very little imagination or insight.