The cover of Julie Delporte’s This Woman’s Work features the author fighting a polar bear with her hands. There’s humor there, but its not a happy joke. Late in the book Delporte shares the dream from which the image of the polar bear is taken. In the dream she settles in a house on a rocky shore which becomes assailed by bears, and has to defend herself with a kitchen knife. “I brandish my knife and plunge it into the bear’s heart,” she says, “I kill him to save my life. It makes me so sad.”

That simple exchange lays bare the stakes throughout the book. Killing dangerous wild animals is just “woman’s work,” the kind of thing you do not because you want or even need to but simply because you must as a natural consequence of being alive, and the unavoidably consequences of this kind of violent struggle naturally preclude so much else. If, as the dream has it, “women's work” is fighting dangerous wild animals, well, then she’s going to have to fight dangerous animals.

The question at the crux of Delporte’s narrative, however, is not actually animal combat but children. Although the book begins with her discussing having children, the question isn’t children per se but the kind of life that children bring: a new life of service. It’s not just getting married or finding the fight person with whom to settle down, no - there’s a more basic conflict, between the urge to procreate and the desire for self-expression. Not completely compatible, especially in the context of potentially flakey men. Men for that matter aren’t actually much of a presence throughout, or rather, exist as presences in the same way that women flit on the edge of more conventional male artist’s narratives - objects just out of the frame, people to be discussed in terms of their impact on the artist’s work, factors but not drivers.

As Delporte puts it while introducing her own family, “my sister used to say she wanted children, but not a husband, and I used to say that if I had children, I’d want to be the father, not the mother.” Much of the book illustrates this point by defining parenthood in terms of, as the title has it, “woman’s work”: taking care of children, to say nothing of the obvious birthing of babies, is the province of one specific gender, but it’s not always the most fulfilling or remuneration position. “How old was I when I started feeling cheated simply by being a girl?” Delporte asks by way of introducing a sequence on the subject of school. As soon as she can read and understand grammar lessons, she learns that the masculine form (in her native French) precedes the feminine.

As Delporte puts it while introducing her own family, “my sister used to say she wanted children, but not a husband, and I used to say that if I had children, I’d want to be the father, not the mother.” Much of the book illustrates this point by defining parenthood in terms of, as the title has it, “woman’s work”: taking care of children, to say nothing of the obvious birthing of babies, is the province of one specific gender, but it’s not always the most fulfilling or remuneration position. “How old was I when I started feeling cheated simply by being a girl?” Delporte asks by way of introducing a sequence on the subject of school. As soon as she can read and understand grammar lessons, she learns that the masculine form (in her native French) precedes the feminine.

When Virginia Woolf wrote about “a room of one’s own,” it was a cultural fantasy for a class of people who had never had any cultural weight, and for whom just the fantasy could be a sustaining lifeline. The problem is that A Room of One’s Own was written ninety years ago. So it’s not like we live in a world without Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, but more to the point we live in a world where the simple observation that women don’t often get to devote themselves exclusively to their own creative pursuits wasn’t enough to change the world overnight. The totem for Delporte throughout her narrative is Tove Jansson, cartoonist, painter, writer, and creator of the delightful Moomin clan. She didn’t have children. She took multiple lovers and wrote a lot of books, drew a lot of comic strips.

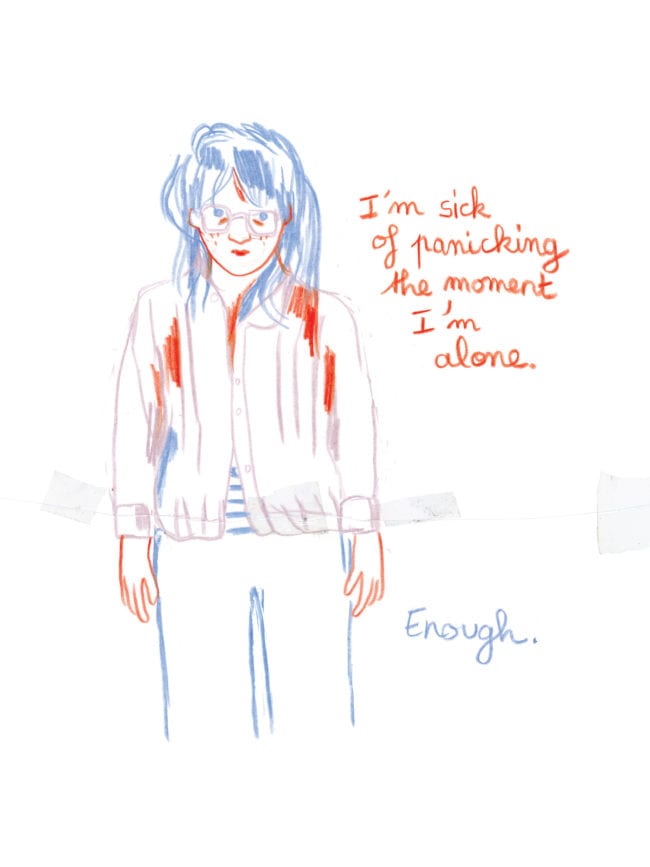

This Woman’s Work, translated into English by Aleshia Jensen and Helge Dascher, takes the form of a first-person personal essay. It’s not a dense narrative. Eschewing panel borders entirely, the story unfolds as a series of still images and collages drawn freely from across multiple periods of her life as well as Jannson’s. Many passages appear directly photocopied from Delporte’s notebooks. Her medium throughout is colored pencils, and it’s such a wonderfully tactile material: you can see the grain of the paper in the artist’s notebooks in a way you can’t with most other mediums, especially in the digital age. It’s difficult to lose track of the fact that these images were handmade.

This Woman’s Work, translated into English by Aleshia Jensen and Helge Dascher, takes the form of a first-person personal essay. It’s not a dense narrative. Eschewing panel borders entirely, the story unfolds as a series of still images and collages drawn freely from across multiple periods of her life as well as Jannson’s. Many passages appear directly photocopied from Delporte’s notebooks. Her medium throughout is colored pencils, and it’s such a wonderfully tactile material: you can see the grain of the paper in the artist’s notebooks in a way you can’t with most other mediums, especially in the digital age. It’s difficult to lose track of the fact that these images were handmade.

I’ve always loved books assembled from artist’s sketchbooks: there’s no more exciting version of comics to me than something small and intricate made by hand and reproduced in such a way as to not merely preserve but to lionize the format’s material limitations. It’s hard to forget that we are supposed to be reading someone’s personal narrative when the story comes in the form of a personal scrapbook or illustrated notebook. A few years back I noticed that more and more books I was receiving from women artists seemed to be going for a raw and studiously rough presentation in terms of medium and execution - specifically, directly reproduced colored pencils seemed to be multiplying. Eventually I came to see the move - a widespread gesture with clear roots in Lynda Berry’s nonfiction comics, among many others - as a studied turn away from the hyperfocus and discipline of the masculine-coded industrial precision of turn-of-the-millennium comics auteurs, to say nothing of the pervasive slickness of most computer-based commercial art in 2019. There’s room to breathe here. Negative space isn’t bound by tight panel grids. She mentions Louise Bourgeois at a couple points throughout the narrative, and you can actually see the influence, with swaths of minimal, almost primary color set as stark central design motifs at various points.

There’s a giant swatch of soft pink floating in an empty paper sky, Commissioner Gordon just set off the Louise Bourgeois signal!

About halfway through This Woman’s Work is a full-page self-portrait by Delporte, perhaps the only such portrait in the book with neither her face nor figure obscured. Jansson shows up throughout the book drawn without a face, as if incomplete or tentative. But on one page, with three colors of pencil - burnt umber, a lavender, and navy blue - she draws a picture of herself full-on, glasses and freckles and cardigan. “I’m sick of panicking the moment I'm alone,” she says in burn umber directly to the reader, before answering “Enough” in a calming and assertive blue. She isn’t as strong and independent as the men she falls in love with, and that seems to hurt almost as much as being attracted to men in the first place.

This Woman’s Work is a monologue about life and love that never once stoops to cliche, or presumes to solve its central dilemma through any kind of pat resolution. There is none. There is instead a gradual sensation of coalescing maturity, as Delporte sifts through her own insecurities and fears in search of some way to square the circle of wanting to be an independent artistic woman who also experiences love and lust. The problem here isn’t so much that Deloporte doesn’t find An Answer, so much as there is no one-size-fits-all solution for any creative person trying to balance life and work, especially in the shadow of children and family. She doesn’t want to be alone but she also doesn’t want to die without expression. Something will probably have to give.

This Woman’s Work is a monologue about life and love that never once stoops to cliche, or presumes to solve its central dilemma through any kind of pat resolution. There is none. There is instead a gradual sensation of coalescing maturity, as Delporte sifts through her own insecurities and fears in search of some way to square the circle of wanting to be an independent artistic woman who also experiences love and lust. The problem here isn’t so much that Deloporte doesn’t find An Answer, so much as there is no one-size-fits-all solution for any creative person trying to balance life and work, especially in the shadow of children and family. She doesn’t want to be alone but she also doesn’t want to die without expression. Something will probably have to give.

Although she doesn't say precisely, the final passages of the book do present a way forward. “What man would be able to live with a feminist?” she asks the reader with her back turned. It’s a question steeped in doubt and regret and even incredulity, but asking it doesn't stop her from decamping to a remote Greek island to draw. She points out that Jansson, despite having partnered with women, also took male lovers at various points. Although she doesn’t actually come out and say, “things sure must be easier without men having to be involved,” she does settle on the fact that even Tove Jansson was able to find a man or two worth the effort. I mean, there have to be at least a couple. Right?