Andy Warner excels at creating bite-sized pieces of unusual history, as seen in his first book, Brief Histories of Everyday Objects. Those observations weren't neutral, as he was careful to discuss the cultural and political ramifications of familiar objects. Much of his other work is more explicitly political in terms of reportage, but his books couch their political barbs in wit and whimsy. In his new book, This Land Is My Land, Warner teams with Danish artist Sofie Louise Dam to tell the stories of micronations, failed utopias, and other such communities throughout history. Simply relating these stories is important because it helps to establish a continuous legacy of resistance not just to the government, but to the entire cultural status quo.

Dam's art is stripped down and cartoony, and it relies a lot on color to tell each story vividly. I found myself wishing Warner had drawn the book himself because I thought his sharper, more naturalistic style would have been a better fit for a lot of the stories. Dam's art does the job and looks beautiful in a few spots, but some of the stories would have benefited from a denser line.

The most important aspect of the book is Warner's extensive research on the subject of these (mostly) failed micronations and utopian projects. Most of the subjects in the book are relatively recent (within the past fifty years or so), and these tend to be less interesting than some of the more ambitious endeavors of the past.

Besides his research skills, Warner's true talent is his ability to synthesize that information into engaging, small chunks. Most of the entries in the book are just four to six pages, yet Warner is able to convey what made each micronation and the people behind them unique and interesting. He uses a weird framing device (a poetic owl opining at length about the urge toward utopianism) which adds little to his narratives. The concept of micronations and utopias isn't so complicated that it requires such a gimmick, and the result is a great deal of distracting padding. The global map and the categorizations Warner uses in arranging these communities provides plenty of information for the reader to get the gist.

The categories he uses are intentional communities, micronations, failed utopias, visionary environments, and strange dreams. The primary distinction is one of internal organization related to pre-existing countries. Micronations, usually as a form of protest or quasi-humorously, tend to replicate existing societal structures on a tiny scale. The other categories are variations on withdrawing from society at large. The most remarkable story is that of Libertatia, a "democratic, anti-authoritarian, and anti-slavery community populated by pirates and former slaves for 25 years." Its existence comes from a tome on slavery, but there's no other proof that it was there on the coast of Madagascar in the 17th century. It's a story of pirates turned crusaders against slavery, attacking slave ships, and freeing those they found.

On the other hand, Freetown Christiania, founded in the 1970s, still exists. It started as a group of squatters in an abandoned army base that turned into a community dedicated to individual freedom, a devotion to the arts and collective ownership. Warner details their struggles with legalizing drugs and how it brought in organized crime, but they still persist, thanks in part to the Danish government giving it a status of "social experiment."

Some of these communities rose and fell around the force of personality of their leaders, like India's Auroville and its "Mother," the Oyutunji African Village in South Carolina and Oba Adefunmi, and the astounding Temples of Humankind in Italy and its founder Falco. He and his followers secretly started building beautiful, elaborate temples in the Alps and went undiscovered for nearly fifteen years. The Italian authorities reversed their initial resistance when they were shown the temples, which has led to a large community built around them that also acts as a tourist attraction. The level of detail in the temples benefits from Dam's art, especially with regard to color.

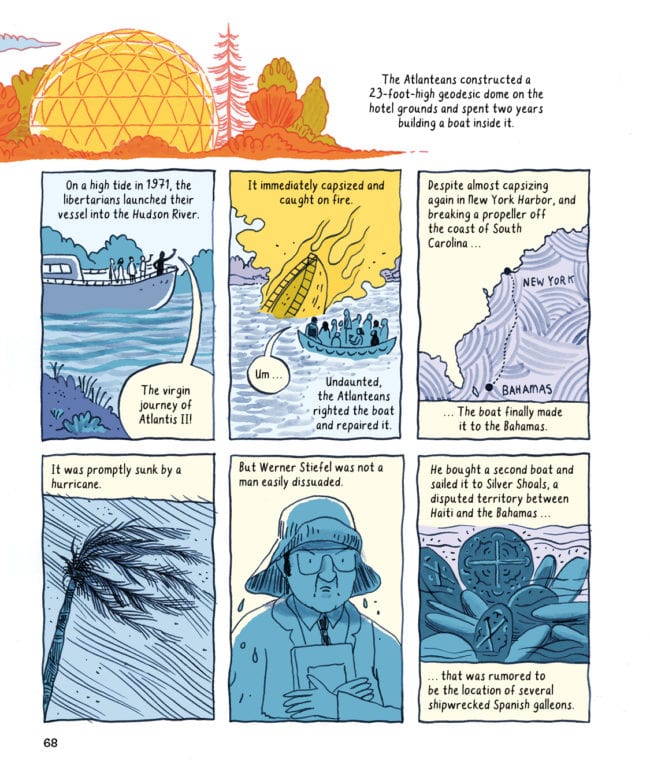

Most of the micronations were started by a single person or a family claiming some kind of off-shore territory or else breaking off a tiny piece of land out of protest. The Principality of Hutt River, for example, began as a protest in Australia against government quotas regarding wheat. The "ruler" dubbed himself a prince "in order to exploit a loophole in a British law from 1495 protecting de facto monarchs," which is the kind of hilarious detail that Warner repeatedly unearths. Unsurprisingly, libertarians triggered some of these micronations, such as Operation Atlantis. In the '70s, one such person put out a notice to build a boat in upstate New York in order to establish a new, free state in the Caribbean. He was worried that America was on its way to becoming a socialist nightmare, but his dreams were literally sunk over and over again by assorted fires, capsizings, and hurricanes. Warner wryly notes that while all this was happening, Richard Nixon was reelected president.

Warner also notes a couple of communities spurred by gay rights, like the Gay and Lesbian Kingdom of the Coral Sea Islands (protesting Australia's ban on gay marriage) and the Van Dykes (a lesbian separatist movement). They range from the whimsical to the life-changing, with members of the latter dropping out of society. A number of utopias were founded on free-love notions, like Oneida in New York. Others, like Fordlandia, were schemes designed to foist the American Way on unwilling subjects. The commonality in their fall usually had to do with increasingly deranged leaders who turned their communities into cults of personality, or else petty concerns getting in the way of ideals.

The "Visionary Environments" section has less to do with the kind of urges for freedom described in the rest of the book and is more about cool art projects. While installations like the Yelang Valley, the Arizona Mystery Castle, and Freedom Cove all have interesting backstories, the urge to make them wasn't quite the same as the other quixotic visionaries in the book. A sameness in some of the stories start to make the book drag, especially since the things that Dam draws start to blur together. A tighter edit of the book would have prevented some of that, especially since some of the anecdotes that Warner relates don't have a lot of narrative meat to them, and the success or failure of each piece depends on him because of the lack of variety on Dam's part. It's a tribute to his overall ability as a writer that so much of the book is so compelling. To be sure, he has a killer hook of an idea, but his painstaking research and wry narrative voice stand out even amid some padding and curious framing decisions.