Contemporary readers tackling early 20th-century horror and weird fiction for the first time are often struck by the lack of character. Protagonists are typically little more than an excuse for first-person narration, rather than complex participants—an extension, perhaps, of the genre’s heritage in stories told around the fire. Algernon Blackwood’s highly regarded novella The Willows is a prime example of this, with a nameless narrator and a companion identified only by his nationality (“the Swede”). This is the first component writer Nathan Carson and artist Sam Ford address in their adaptation, serialized in two halves by indie publisher Floating World Comics and soon to be collected in one volume.

Where Blackwood, a contemporary of H.P. Lovecraft’s, drops two largely anonymous men into a canoe floating down the Danube, Carson and Ford have substituted Opal and Hala, female companions with clear motivations for bucking societal expectations and setting out on an extended wilderness expedition. (There’s a hint that Opal and Hala are more than just traveling companions, but this path isn’t followed far.) Carson develops each woman just enough to help explain the madness-induced choices made during Blackwood’s original tale, and a newly added “origin story” following the main narrative in this collection suggests that Carson and Ford would like to return to their lady explorers for further adventures.

Aside from Opal and Hala, Carson and Ford stick fairly close to the original Blackwood, with mixed results. Anyone who has ever attempted to read Lovecraft knows that the progenitors of weird fiction loved prose on the purple end of the spectrum, and while Blackwood is a stronger writer than Howard Phillips on a pure craft level, much of the enjoyment of Blackwood’s work still comes from losing yourself in the ornate language. Carson maintains many of Blackwood’s most memorable passages, but this leaves Ford in a bit of a bind: he can either hew close to the literal descriptions of nature in the accompanying text, or he can get playful. He chooses the latter option, and his visualization of Blackwood’s descriptions are inventive—a map that slowly floods into an actual river, a Klimt-like flourish of rushing water, a foreboding serpent that dissolves into musical notes—but this inventiveness is called upon from the very first page, robbing the narrative of a carefully paced ascent into cosmic horror. What Hala and Opal experience on a small islet in the middle of the Danube throws doubt on reality and sanity, yet there’s little to separate moments of existential dread from Ford’s non-terrifying visual metaphors. Imagine if Nightmare on Elm Street, Requiem for a Dream, or It opened with the protagonists having happy hallucinations.

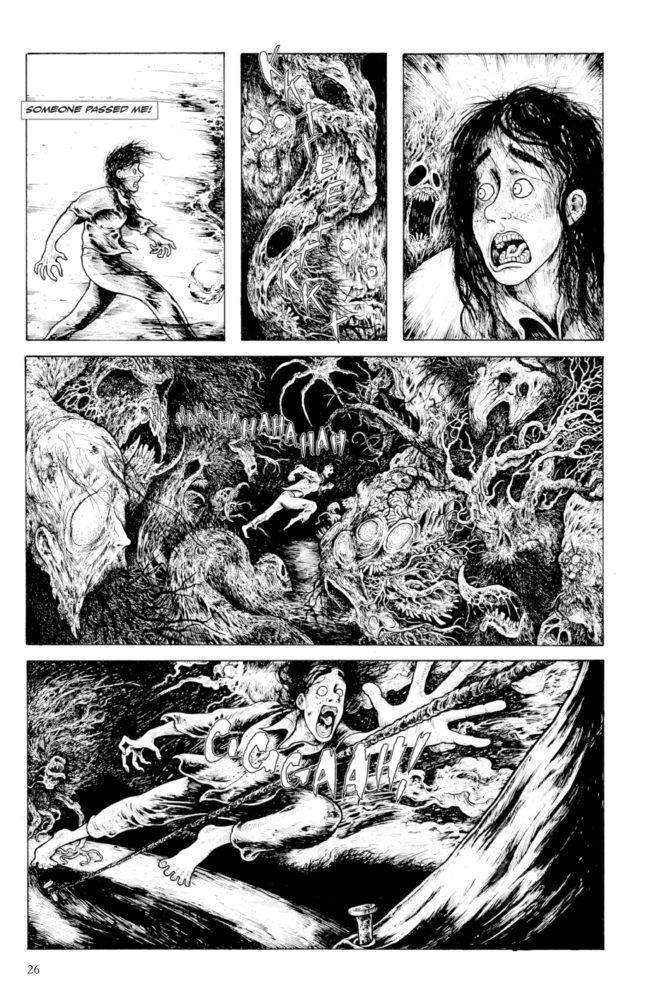

Still, these visual flourishes are where Ford best fits the material, and his monsters from beyond the veil don’t disappoint. Berni Wrightson’s melting mounds of flesh from The Amazing Spider-Man: Hooky are a good point of comparison. Tasked with depicting the indescribable, Ford molds his tentacle-strewn horrors out of campfire smoke, rippling water, sandy riverbanks, and gusts of wind, leaving it up to the reader to decide which visions Opal and Hala are actually witnessing and which they’re only imagining in the shadows of their willow-strewn landing spot. And while the previously mentioned visual metaphors do undercut the surprise of the more frightening imagery, the hazy divide between nature and the terribly unnatural is a perfect distillation of the original novella’s themes.

Still, these visual flourishes are where Ford best fits the material, and his monsters from beyond the veil don’t disappoint. Berni Wrightson’s melting mounds of flesh from The Amazing Spider-Man: Hooky are a good point of comparison. Tasked with depicting the indescribable, Ford molds his tentacle-strewn horrors out of campfire smoke, rippling water, sandy riverbanks, and gusts of wind, leaving it up to the reader to decide which visions Opal and Hala are actually witnessing and which they’re only imagining in the shadows of their willow-strewn landing spot. And while the previously mentioned visual metaphors do undercut the surprise of the more frightening imagery, the hazy divide between nature and the terribly unnatural is a perfect distillation of the original novella’s themes.

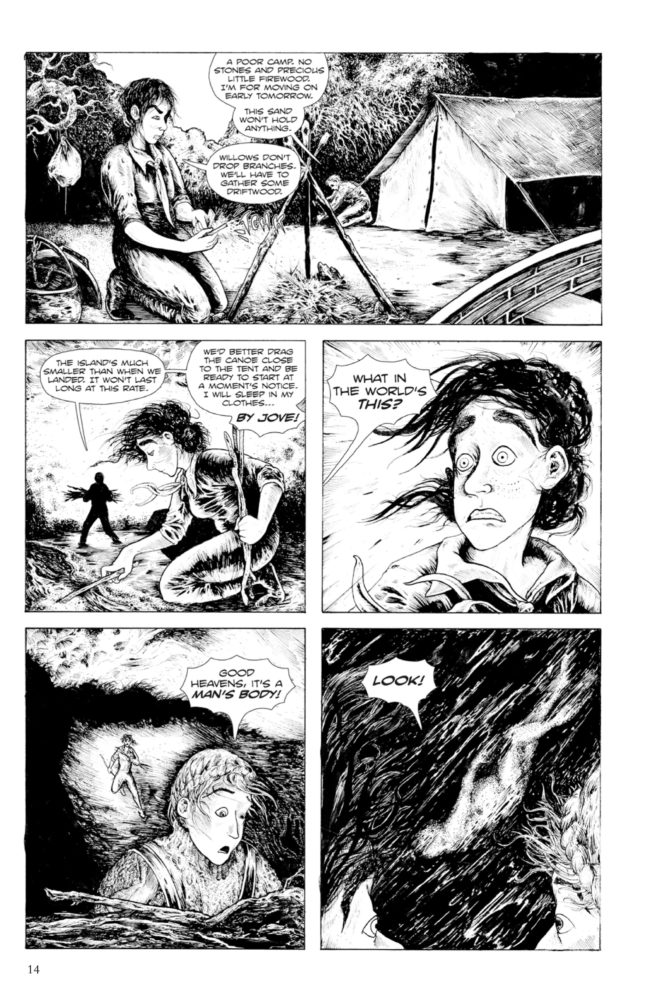

It’s a bit ironic that Carson and Ford’s contribution to The Willows is a pair of defined protagonists; Ford, an experienced illustrator who apprenticed under Concrete creator Paul Chadwick, struggles most when it comes to Opal and Hala. While the flora, fauna, and monstrosities of the Danube receive a level of detail fit for scientific illustration, the faces and anatomy of the human leads are far less consistent. A contrast in cartooning between figure and background can go a long way toward instilling a sense of the uncanny in horror comics: Gou Tanabe’s too-pretty characters in his Lovecraft adaptations, Kengo Hanazawa’s exaggerated acting against photo-realistic backgrounds in I Am a Hero. But in the pages of The Willows, Ford’s facial work simply feels unrefined, and repeated, repetitive depictions of slack-jawed shock fail to convey the enormity of Blackwood’s existential terror.

It’s a bit ironic that Carson and Ford’s contribution to The Willows is a pair of defined protagonists; Ford, an experienced illustrator who apprenticed under Concrete creator Paul Chadwick, struggles most when it comes to Opal and Hala. While the flora, fauna, and monstrosities of the Danube receive a level of detail fit for scientific illustration, the faces and anatomy of the human leads are far less consistent. A contrast in cartooning between figure and background can go a long way toward instilling a sense of the uncanny in horror comics: Gou Tanabe’s too-pretty characters in his Lovecraft adaptations, Kengo Hanazawa’s exaggerated acting against photo-realistic backgrounds in I Am a Hero. But in the pages of The Willows, Ford’s facial work simply feels unrefined, and repeated, repetitive depictions of slack-jawed shock fail to convey the enormity of Blackwood’s existential terror.

Carson, a metal drummer and weird-fiction author, does a solid job of picking up enough of Blackwood’s original text to maintain authenticity without crowding Ford’s artwork, but the pacing of events isn’t always ideal. Opal and Hala’s first big brushes with the ominous and the unknown, pulled straight from the novella, speed along in just two back-to-back pages. Ford makes the first, a shape in the water that may be either a dead body or an otter, work well in the allotted space. The second, a ghostly boatman glimpsed against the light of the setting sun, is more rushed, seeming to be a continuation of the otter incident until expository dialogue clarifies otherwise. In the afterword, Carson points out that the novella’s original ending is anticlimactic, and that he and Ford sought to tweak it into a more “appropriately weird and mysterious ending” that has been “appreciated by every reviewer to date.” Not to invalidate that statement, but this reviewer found Carson and Ford’s ending just as abrupt as Blackwood’s original, to the extent that readers may keep flipping pages in search of a more definitive conclusion.

Carson, a metal drummer and weird-fiction author, does a solid job of picking up enough of Blackwood’s original text to maintain authenticity without crowding Ford’s artwork, but the pacing of events isn’t always ideal. Opal and Hala’s first big brushes with the ominous and the unknown, pulled straight from the novella, speed along in just two back-to-back pages. Ford makes the first, a shape in the water that may be either a dead body or an otter, work well in the allotted space. The second, a ghostly boatman glimpsed against the light of the setting sun, is more rushed, seeming to be a continuation of the otter incident until expository dialogue clarifies otherwise. In the afterword, Carson points out that the novella’s original ending is anticlimactic, and that he and Ford sought to tweak it into a more “appropriately weird and mysterious ending” that has been “appreciated by every reviewer to date.” Not to invalidate that statement, but this reviewer found Carson and Ford’s ending just as abrupt as Blackwood’s original, to the extent that readers may keep flipping pages in search of a more definitive conclusion.

It must be said again that weird fiction and classic horror are hard to adapt. Lovecraft inspires far more derivative drivel and Cthulhu-obsessed sci-fi/action than he does faithful realizations of his anxious themes. Successful adaptations like I. N. J. Culbard’s and Tanabe’s are the exceptions that prove the rule. Carson and Ford’s take on Algernon Blackwood’s The Willows gives the story characters, plural, but it's the original text that still has more character.