My quietness has a man in it, he is transparent and he carries me quietly, like a gondola, through the streets. -- “In Memory of My Feelings”, Frank O’Hara

The cartoonist Gabrielle Bell is what might have happened if Emily Dickinson had ever gotten out of the house. In her graphic memoir The Voyeurs, Bell—a recluse even in a crowd—studies different kinds of loneliness with the sort of singular interest that most people reserve for more pleasant tasks, like sampling wedding cakes. Grounded by a self-deprecating sense of humor, she has a gift for exploring the fullness of silence that shares its DNA with Dickinson’s dashes. There’s a coy sort of melancholy in its restraint, but it’s buoyed by the great faith it must require to trust the reader to fill in those pauses just so.

In Bell’s hands, comics are poetry’s cool little cousin, all slippery meanings, feats of peculiar punctuation, and the unfortunate tendency to namedrop the likes of Bertolt Brecht. She avoids the threat of pretension that’s implicit in all of those things with well-timed flashes of humor and a vague distaste for anything she can’t do on the Internet. She’s never mean or insincere or trying too hard; she just is in a way that’s both refreshing and a little autistic.

Above all, The Voyeurs is a master class in pacing. Bell’s use of panels in particular gives even her most straightforward stories an additional register of beats and pauses that words and images on their own can’t achieve. Her slightly wobbly grids offer a soothing sort of sameness that occasionally ends on a long silent beat, leaving both Bell and the reader to mediate on the landscape.

The trick is she’s thoughtful without being moody. Bell’s work has a transcendent quality that stands out in the chaotic milieu that is autobiographical comics, achieving a clarity of tone that is deceptive in its simplicity. Is that what life feels like when you do a lot of yoga? I myself am into zumba, which is telling.

Like Frank O’Hara, Bell’s home is New York City, and a lot of her stories take place while she’s walking around. She ignores the more flashy aspects of the weirdness of that place in favor of its subtle surreal qualities, which she teases out expertly from otherwise banal afternoons. While her stories are almost entirely autobiographical, there’s a certain fluidity between fantasy and reality that marks the way she takes in the world. It’s a defense mechanism, perhaps, but it’s totally charming.

Like Frank O’Hara, Bell’s home is New York City, and a lot of her stories take place while she’s walking around. She ignores the more flashy aspects of the weirdness of that place in favor of its subtle surreal qualities, which she teases out expertly from otherwise banal afternoons. While her stories are almost entirely autobiographical, there’s a certain fluidity between fantasy and reality that marks the way she takes in the world. It’s a defense mechanism, perhaps, but it’s totally charming.

Appropriately, Bell’s reality seems most tenuous when she’s traveling abroad with her (now ex-) boyfriend, the director Michel Gondry. Away from home, she keeps to herself, asleep for long stretches like a lady in a fairytale. In Tokyo, she withdraws from a media whirlwind by fixating on a bowl of pretty candies. In France, Gondry jokes that he couldn’t tolerate her if she weren’t so talented—which is also, as it happens, his blurb for the book. Life that imitates art that imitates life? In a word: whoa.

Appropriately, Bell’s reality seems most tenuous when she’s traveling abroad with her (now ex-) boyfriend, the director Michel Gondry. Away from home, she keeps to herself, asleep for long stretches like a lady in a fairytale. In Tokyo, she withdraws from a media whirlwind by fixating on a bowl of pretty candies. In France, Gondry jokes that he couldn’t tolerate her if she weren’t so talented—which is also, as it happens, his blurb for the book. Life that imitates art that imitates life? In a word: whoa.

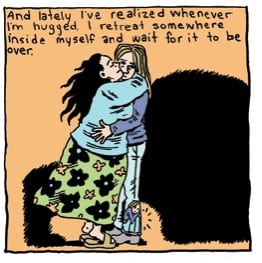

The Voyeurs is a heavily edited version of Bell’s web comic, Lucky, the Internet diary that she’s maintained for many years. The demands of that format inform the book’s meta thread, wherein the cartoonist reflects on the ways in which her art intersects with her life. (One gets the sense that Bell might never leave her apartment again if she ever decides to traffic in fiction.) These episodes, as well as her niggling sadness, sometimes make her seem like a ghost who’s haunting her own life. The self as a voyeur—someone who likes to watch—is a take on postmodern detachment (and more narrowly, what it means to be a writer) that strikes me as thoroughly correct; in any case, it’s one way to articulate the increasingly palpable strangeness of contemporary life, where even flesh and blood can feel like an avatar. As Bell’s body moves around in the world, her spirit is at home, drawing comics.

The Voyeurs is a heavily edited version of Bell’s web comic, Lucky, the Internet diary that she’s maintained for many years. The demands of that format inform the book’s meta thread, wherein the cartoonist reflects on the ways in which her art intersects with her life. (One gets the sense that Bell might never leave her apartment again if she ever decides to traffic in fiction.) These episodes, as well as her niggling sadness, sometimes make her seem like a ghost who’s haunting her own life. The self as a voyeur—someone who likes to watch—is a take on postmodern detachment (and more narrowly, what it means to be a writer) that strikes me as thoroughly correct; in any case, it’s one way to articulate the increasingly palpable strangeness of contemporary life, where even flesh and blood can feel like an avatar. As Bell’s body moves around in the world, her spirit is at home, drawing comics.

It’s fitting, I think, that the introduction to The Voyeurs was written by the punk icon Aaron Cometbus. As a kid, his zine helped me see that there was a wide world beyond the confines of my own Tennessee cowtown in a way that made me feel hopeful about my life. Now, as an adult with mobility, I see the real difficulty is in pushing past the limits of a more interior landscape. In that task, I’m glad to have Bell as a guide. You could say The Voyeurs is the work of a writer’s writer, but it’s actually something more cool, more exotic, more punk: a rare glimpse of the fiercely mysterious human heart, observed in its natural habitat.