"Art loves a constraint", says Strumpet editors Jeremy Day and Ellen Lindner, explaining why their anthology is open only to women. They also note more practical reasons: "We're keen to support women artists, to provide a social network, and a place to experiment and tell their stories." It should be noted that The Strumpet has its roots in an anthology called Whores of MENSA edited by roughly the same crew (plus Sacha Mardou). The title was a clever reference to an old Woody Allen short story; unfortunately, the sticks-in-the-mud over at MENSA chose to issue a cease-and-desist order. This may well be all to the better, considering that The Strumpet is the product of many years' experience assembling anthologies.

The collection is yet another sign that British cartoonists are not only establishing themselves as a force to be reckoned with in the alt-comics world, they're interfacing directly with American artists as well. Indeed, the comic notes its "transatlantic" nature on its cover, and the mix of European and American artists is a seamless one. Back when it was still Whores of MENSA, one declared reason it included only women was to give female British cartoonists a place and space to publish on their own terms. If British alt-cartoonists were a rare breed a decade ago, then women in that category were even more scarce, and so the anthology had a practical consideration as well as an aesthetic one. Every issue was themed, and the first issue of The Strumpet doesn't break that trend; it's "the dress-up" issue, a concept the editors tie to transformation. Like some past publications that Lindner released, there's some more zine-like content as well, including reviews and an interview with and prose piece by zinester (and TCJ.com contributor) Katie Haegele.

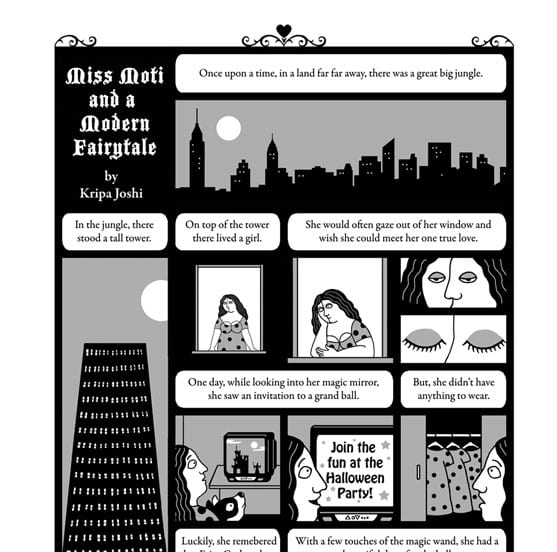

The comics content is quite strong, emphasizing a variety of visual and narrative approaches to the idea of dressing up. The first piece, by Kripa Joshi, is an attention-grabber because of the strong way that she spots blacks in her modern fairytale update. Patrice Aggs' piece is its total opposite, with a fine line, naturalistic approach and a loud, bawdy tone in a story about a highly unconventional model at a photo shoot. Lisa Rosalie Eisenberg's story takes yet another different turn, with a cartoony line and use of greyscale in a story about a man who dresses up like a cat in order to hang out with his own pets and literally go catting about town. Eisenberg stretches what would seem to be a thin premise as far as it will go but never lets it wear out its welcome. This is a nice one-two-three punch to open up an anthology, though the best stories are yet to come.

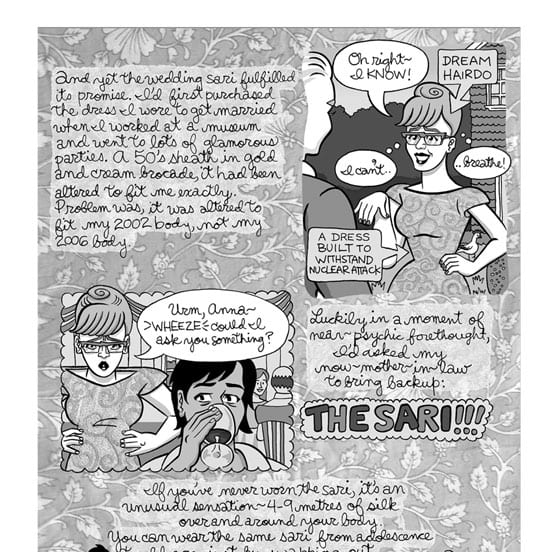

The entry that made me laugh out loud was Mardou's "Mint Condition", a story about a female cartoonist at a comics convention who swoons over smelly fanboys and secretly craves their attention like a romance comic heroine (and even notes that her outfit was inspired by a 1972 Gene Colan romance story). After she relishes a fanboy glancing at her cleavage, she laments, "Sheesh, I know I'm no Scarlet Witch, but do you have to look so unimpressed?" Lindner's "Me and My Sari" is one of her delightful autobio stories that details how a sari (a traditional Indian garment) was made for her by one of her future relatives, and how wearing it at her wedding reception allowed her to actually dance and move freely. The story, told in Lindner's breezy style and and with an eye toward her art's more decorative qualities, touches on the ways that breaking out of her very white upbringing have opened up her life.

After Lindner's story, which contains almost no negative space because of its decorative focus, Maartje Schalkx's story about a Dutch nun who enclosed herself in a small room for devotional purposes is almost entirely negative space. The use of panels to demarcate time and action winds up being some of the dominant linework on each page until Schalkx gives a single close-up of the nun before she finally dies in her room, 57 years later. It's a very clever exploration of line, space, and figure that is totally unlike anything else in the book. It's followed by Jeremy Day's ramshackle, casual and scribbly line that gives solidity to its figures with various patterns on clothes. It's a fantasy story involving the creation of paper dolls for a group of poorly-dressed faeries who demand new outfits or else the protagonist will not be left alone to sleep. The narrative and figures lurch across the page with expressive, spontaneous lines that eventually resolve into an elegant solution.

The other noteworthy piece is Megan Kelso's "The Good Witch", a full-color comic on the back cover that covers familiar ground for her. Once again, Kelso elegantly uses text and image to tell two slightly different stories, as the text is from the point of view of two young girls and the images (of a mother dropping off her two young children at their grandmother's house) tell a slightly different story. I loved Kelso characterizing the older woman as "timeless, like a fairy tale" and "a different species." She captures that certain magic that children, if they are lucky, can feel with grandparents and other older relatives, a sense that an adult is actually in cahoots with them to have adventures. In many ways, it's a sweeter take on childhood than I've seen in some of her past work, but there's no question that she's got the rhythms down pat.

Kelso's and Schalkx's stories are the best overall, but there are no weak links in this issue, even if a couple of the stories tread on similar story ideas. The story by Haegele is enormously evocative, the reviews are crisply written and everything about the design and format of this anthology is attractive and eye-catching. This is a great example of how Kickstarter can energize and improve a project in allowing higher production values and an increased page count. I hope that Lindner and Day can keep it going.