Dave Stevens’ The Rocketeer was many things: iconic, lushly drawn, technically astonishing, pulpy, movie-mad. It reinvigorated the culture of pinup drawing, revitalized Bettie Page’s career, kickstarted the retro revolution, and made superheroes safe for the nascent creator-owned 1980s.

But now that there’s been three times more Rocketeer comics created after Stevens’s death than actually drawn by Stevens, it’s time to face facts: The newbies do it better. Stevens’s Rocketeer recovered much of 1930s and 1940s popular culture—its slang, its movie posters and Hollywood PR campaigns, its fashions, its underground burlesque, its plucky “can-do” spirit. Recovery without reinvention, though, only goes so far, and The Rocketeer largely coasted on its premise and charisma. It was many things but what it mostly wasn’t was a good comic.

Looking back at The Rocketeer: The Complete Adventures, it’s easy to see why. Stevens’s sources were still illustrations—pinups, “good girl” art and photography, technical specs of airplanes and automobiles, archival photos of period architecture and machinery. He loved illustration and in some ways he’s the greatest Ellery Queen cover artist that never was. But illustration ain’t comics, and Stevens’ Rocketeer often seems uninterested in its own form.

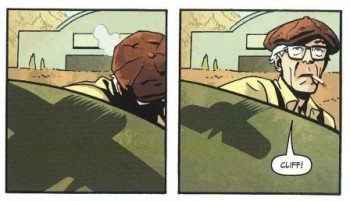

Indeed, Stevens reminds me less of other cartoonists than of filmmaker Michael Bay. Take page 38 of IDW’s Complete Adventures:

Panel by panel, Stevens creates gorgeous images, just as Bay’s individual compositions are often breathtaking. Taken together, though, those panels and frames add up to confusing messes. Perspectives don’t match from panel to panel. The layouts are unnecessarily messy. The cram of information, as well as radical shifts from panel to panel, makes for a difficult reading experience. Each panel electrifies but each page is a muddle.

Stevens loved the patois of old cinema—circular panels that resemble iris shots; split panels broken by zigzags instead of straight lines; dramatic angles above and below characters, and from between their legs. But he used them indiscriminately, like a self-conscious teenager eager to show off his technical facility.

That facility was amazing, and that’s part of the problem. No one in mainstream comics could draw a curvy woman as lusciously as Stevens could. Few captured the minor details of a plane or a car as rigorously as he could. That illustrative knack, though, made for a near-photorealism that creeps up to the uncanny valley. (The IDW version’s computer-shaded coloring doesn’t help matters.) Stevens’s art distances us for identifying with his characters.

Not that there’s much characterization to begin with. After 140 pages of The Rocketeer, we don’t know much more about Cliff Secord and his world than we do on page one. That world looks pretty, and Stevens’s research ensures that it’s populated with the right slang, tailored cuts, and auto models and makes. Its people, however, are mere icons, not characters.

Betty, Cliff’s on/off girlfriend, symbolizes the problem. Again, we see echoes of Michael Bay, who also uses women as pinups rather than as lived-in people, who also is more interested in how a girl is lit than in how she thinks. It’s telling that the two most iconic (and Googled) images of The Rocketeer are of Betty, not its titular hero:

Both are especially static images, perfect for a magazine cover. Stevens’s covers are often more arresting than the comics inside them. They reveal plenty of Betty’s voluptuousness but little of her mind. Of course, it’s unfair to extrapolate Stevens’s intent from two pages but these slices of cheesecake are all of a piece. Page 97 seems especially representative, and thus gratuitous. Her body stands in a pinup pose, completely with partially parted lips, overlaps panels of Cliff and Goose discussing her. We know from their conversation that Betty is on Cliff’s mind, so we don’t need the splash of her gams to get that. Her expression reveals nothing of what she’s thinking of Cliff. So why is the page’s left side so occupied with her? Because it’s cool-looking, and it’s sexy. The boldness of the layout hides its lack of necessity.

What we need to know—about Cliff, Betty, Peevy, and even the rocketpack itself—is usually what Stevens doesn’t offer. The cartoonist gave Cliff’s lengthy backstory as text—reproduced as jacket flap for the IDW edition—in a 1985 limited edition. But we don’t get it in the comics themselves. What makes Cliff tick? How do he and his mechanic (Peevy) know each other? Why are they friends? Why do Cliff and Betty love each other? Where, exactly, does that rocketpack come from? Who made it? All are unanswered in the comics. The result is a superhero comic with a dull cipher at the core. Even his mask is inexpressive and gestureless.

The cipher’s not even all that heroic. Cliff’s exploits serve entirely selfish purposes—he rarely serves anyone that’s not directly related to his life. The rocketpack is his ticket to fame, not a device to help others. Cliff doesn’t even have a code of honor extending beyond himself—his first impulse is to punch first, and run like a coward later. The comic’s entire run consists of adventures that serve no larger goal, and have no larger ramification, than Cliff’s satisfaction. Compare this to Superman saving the world, Batman and Spider-Man fighting crime in the streets, and the Green Lantern exploring the cosmos, and you see how small-scale and self-serving the Rocketeer is. In that sense, Cliff reflects his creator’s style: He’s a demo reel of his own gifts, eager to show off his talents for commercial gain. Like Michael Bay, who started out doing TV commercials, Stevens is a huckster at heart.

For all of The Rocketeer’s failures as a comic, it’s perhaps the most successful icon of the 1980s creator-owned boom. There’s so much promise and pizzazz in that chrome mask and jaunty pose that cartoonists return to Steven time and time again. Stevens built his comic on a flair for nostalgia—for a past that never was—which is a heartache that artists and readers have and long to feed. The nostalgia, I think, helps us glide over the comic’s narrative gaps and characterization issues. Those caesuras allow room for others to fill in the iconography with their own visions. The Rocketeer’s incompleteness and flaws become, then, a boon to a talented writer/artist team.

That leads us, finally, to the newbies: Mark Waid and Chris Samnee’s The Rocketeer: Cargo of Doom and Roger Langridge and J. Bone’s The Rocketeer: Hollywood Horror. These Rocketeer graphic novels extend the brand—and what is an icon but a really successful brand, after all?—by improving on the source. These teams have fashioned two remarkably rewarding adventure comics, and honor Stevens’s creation by bettering it.

Cargo of Doom starts with a humdinger airborne rescue, and doesn’t let up for its 100 pages. Its bold lettering, clean layouts, and suspenseful pacing come through on the first page:

Note the attention to process—cause and effect—in these panels. Neither Samnee’s art here nor Bone’s in Hollywood Horror concerns itself overmuch with physical detail, at least not to the extent of Stevens’s obsessiveness. Samnee, though, uses his comics to convey motion and transition, something that Stevens’s static calendar poses rarely conveyed convincingly. (It’s weird that, for all the explosions and uppercuts, Stevens’s art looks so stiff.) That fifth panel, in particular, is a marvel of concision, capturing an enormous sound and dangerous movement all at once, as the panel is itself a literal gigantic whoosh.

Two pages later, Waid and Samnee give us two panels in succession that reveal plenty, just though a shadow passing over a metallic surface:

That sort of pause happens rarely in Stevens’s comics. They’re frenetic. Waid/Samnee and Langridge/Bone go full throttle, too, but there’s a sense of pacing, chances to catch your breath, pauses to reflect.

Cargo of Doom and Hollywood Horror pay homage to the original Rocketeer’s through the golly-gee tone, screwball dialogue, and odd-shaped panels. Despite their aesthetic differences, both books are grounded by Jordie Bellaire’s muted but glorious color schemes, which glows with subtle browns, yellows, reds, and burnt oranges. Even the blue skies look as if seen through a sepia filter, evoking faded movie posters. (In terms of branding the character, Bellaire may be IDW’s best asset.) Cargo is gorier than anything Stevens drew, and Hollywood contains more good slapstick on one page than Stevens pulled off in his entire run. Langridge—creator of the slaphappy Fred the Clown and cartoonist behind the Muppet Show revamp—lets his sly wit fly. Parodies of Laurel and Hardy, The Thin Man, Tintin’s Thompson and Thomson, Clark Gable, Albert Einstein, and more flit through the pages, in a MAD Magazine-like frenzy. Bone keeps pace with Langridge’s ideas, often channeling Jack Kirby:

As artists, Samnee and Bone, though different stylistically, both emphasize the pure fun of a dude being able to fly with a jetpack. That’s something oddly absent in Stevens’s original. We rarely, relatively speaking, see the Rocketeer in action in his pages. Stevens’s Rocketeer is stuffed with incident, but most of it’s cheesecake, dialogue, exposition, flashback sequences, and planes flying. Cargo and Hollywood wisely suffuse their tales with the derring-do and rescues that we paid to see. They’re less wordy than Stevens’s comics, and the words they choose are punchier and stronger. Waid/Samnee and Langridge/Bone introduce a plethora of villains and sidekicks cleanly to Stevens’s universe. The characters’ relationships to Cliff, and their quirks and tics, get revealed through gesture and action.

Again, there’s plenty of action. The “Cargo of Doom” in question is a crate of dinosaurs. Of course, they get set loose on Los Angeles, drawing allusions to everything from King Kong to Mark Schultz’s Xenozoic Tales—incidentally a contemporary of and competitor with The Rocketeer. The explosions and calamities are conveyed with appropriately sized splash pages, sure, but also with minimal fuss and beautiful silences.

In Hollywood Horror, Langridge and Bone skew closer to the zippy line and broad slapstick of Looney Tunes cartoons than Stevens’s photorealism. The faces and physiques could come straight from Dick Tracy. The architecture and scenery, even more so than Cargo of Doom, are minimalist backdrops. Gesture is king, as befits a comic about a dude who flies with a jetpack and a dame with Bettie Page’s curves.

Langridge and Bone allow Betty to be more than a fappable fantasy—something Stevens never achieved (or, let’s be honest, was even interested in achieving). In fact, the desire to participate in her boyfriend’s exploits is one of the graphic novel’s key plot devices.

Drawn here, Betty’s certainly sexy but she’s not static. Even the dynamism of the panel sizes and closeups here, on one page, emphasize that we’re going to see her from more angles—physically and emotionally—than Stevens considered. Shapeliness doesn’t shape her, at least not fully.

Cliff’s a looker, too, though both these cartooning teams make sure he gets punched up a fair bit. Bone in particular makes his jaw so square that it’s a mockery of Superman’s mug, just begging to get clocked. Like Superman, these new incarnations of the Rocketeer want to save the day, not just themselves. In Hollywood Horror, Cliff stops a mad scientist from blowing up the Los Angeles dam and hypnotizing the city. In Cargo of Doom, he keeps dinosaurs from demolishing the town. Sure, he wants his pilot’s disguise and shot at the movies but that rocketpack’s got bigger, and more selfless, plans for him.

IDW, it appears, has bigger plans for The Rocketeer than its creator envisioned. With these two long-form adventures, at least, the character is finally living up to his iconic status, as a hero and—most importantly—as a comic.