It’s a tricky thing, modernizing or adapting a time-honored fable : everybody (presumably, at any rate) already knows the outcome, to be certain, as well as most of the steps it will take to arrive there, so any value you can add comes not by way of innovation, but solely by way of re-interpretation --- in other words, you’d better have something damn interesting to say, or have discovered any entirely new angle from which to view the story, otherwise you may as well just leave things as they are and either try your hand at something wholly original, or report to the day job.

British cartoonist Liam Cobb, then (best known to American readers --- to the extent that he’s “known” here at all --- for doing some fill-in work on the Image Comics series Spread, a rather clever and grotesque, but certainly unspectacular, post-apocalyptic hybrid of Lone Wolf And Cub and John Carpenter’s The Thing) has set out a rather daunting task for himself with his new Retrofit/Big Planet release, The Prince, in that it’s not just an updating of any old fable, but perhaps the best-known fairy tale of all, “The Frog Prince.” At first glance, I’ll admit, the cynic in me was tempted to just shrug and say “yeah, good luck with that,” but when I opened the stylish cover, I discovered something rather unlike what I had been expecting.

The just-referenced cover sets the tone for the interior contents quite nicely, as Cobb employs a vaguely Mad Men-esque sensibility that could possibly best be described as “retro-futurism” to convey a briskly-told, emotionally-distant, decidedly vengeful version of an ostensibly simple yarn. His conceit of making the frog a mysterious, and possibly duplicitous, sudden arrival into the life of May, a neglected, financially well-to-do wife trapped in a loveless marriage with a typically philandering scoundrel of a husband adding a frisson of tension and unease to one of the most shop-worn plot skeletons you’d care to mention. It’s an intriguing enough wrinkle to keep you turning the pages, to be sure, but is it actually innovative?

The just-referenced cover sets the tone for the interior contents quite nicely, as Cobb employs a vaguely Mad Men-esque sensibility that could possibly best be described as “retro-futurism” to convey a briskly-told, emotionally-distant, decidedly vengeful version of an ostensibly simple yarn. His conceit of making the frog a mysterious, and possibly duplicitous, sudden arrival into the life of May, a neglected, financially well-to-do wife trapped in a loveless marriage with a typically philandering scoundrel of a husband adding a frisson of tension and unease to one of the most shop-worn plot skeletons you’d care to mention. It’s an intriguing enough wrinkle to keep you turning the pages, to be sure, but is it actually innovative?

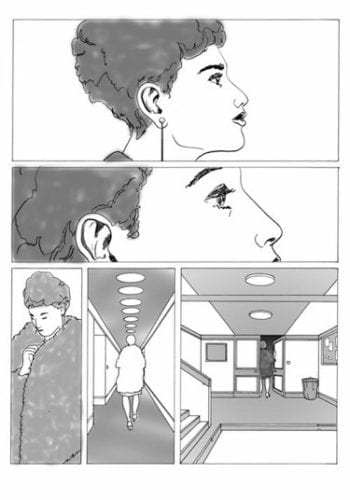

Well, yes and no --- “yes” in that transposing the tale’s setting to the world of fashionable, high-rent-district apartments and dressed-to-the-nines cocktail lounges feels like a natural enough move thanks to Cobb’s sparse, economic dialogue and sleek illustration that frequently renders “important” figures in stark relief in the foreground while consigning others to the fate of shapes and outlines, ultimately of less significance than their detailed surroundings and environments, making it clear who and what matters and who is mere “background noise” in this competition of competing polarities rooted in self-interest. The book has a holistic visual approach that Cobb sticks with, to his credit, doggedly, living or dying (metaphorically speaking) by his initial --- and pretty damn strong --- vision and conceptualization. So where does the “no” come in, then?

I certainly give Cobb points for trying, especially since there are so many instances in the narrative where a bit of comic relief, if done right, could make for a successful contradistinction with the cold-hearted machinations of two deeply flawed people navigating for a “win” in a quietly crumbling marriage, but when you’re trying to set your frog up as a Serpent of Eden-type figure, complete with dangerously alluring eroticism, falling back on slight-but-obtrusive flashes of old-school “funny animal” humor is simply too jarring when delivered within a framework of otherwise-relentless emotional austerity.

I certainly give Cobb points for trying, especially since there are so many instances in the narrative where a bit of comic relief, if done right, could make for a successful contradistinction with the cold-hearted machinations of two deeply flawed people navigating for a “win” in a quietly crumbling marriage, but when you’re trying to set your frog up as a Serpent of Eden-type figure, complete with dangerously alluring eroticism, falling back on slight-but-obtrusive flashes of old-school “funny animal” humor is simply too jarring when delivered within a framework of otherwise-relentless emotional austerity.

All things considered, though, Cobb gets more right here than he does wrong, and despite a uniform overall tone and presentation, most of the characters, particularly May, come across as genuine individuals, and motivations for everyone are as clear and concise as the book’s linework and page layouts --- apart from the frog, of course, whose rationale and ultimate aims are left deliberately oblique for as long as possible. The Prince, then, is probably best viewed as an intriguing experiment that flirts with essential reading status only to occasionally undercut itself by punching outside its weight class. At least it offers a novel, if less than wholly necessary, take on a concept that’s been done to death.