For Germany's leading cartoonist Anna Haifisch the fluorescent honeymoon between To Live and Die in L.A. and Miami Vice is definitely over. Her latest release The Mouse Glass is implementing a further decisive step in her constantly evolving chromatic ideology. Last year's Drifter, also released via Haifisch's publisher Perfectly Acceptable Press (which also works as a kind of an experimental laboratory) marked the turn from melancholy-drenched dramedy to endogenous depression. But for now it's time to fight back the oppressors.

While Drifter took pleasure in mostly recapitulating color schemes already proven in predecessors like Von Spatz or The Artist series, The Mouse Glass focuses on establishing harsh contrasts, for example between the luminously bright fires in yellow resulting from the attacks of marauding street fighters and the environment surrounding them, laid out in large green and orange flats on the cover. In times of war, the light flair of her former works has to step aside for a kick in the eye.

A color code telling a tale itself is being established here, also in ways of a conceptual array bookbinding-wise: Like one of the Hamburg riots in July 2017, with protesters against the G20 summit never able to reach their targeted addressees, who remained safe and snuggled up in their highly guarded comfort zones. Haifisch's protesters either never make in into the book, where a summit between several species of animals is happening, or they remain on the cover, foreclosed for all eternity.

Though the outrage and the combinations of colors depicted on the frontispiece show up again during a congress of the animals, The Mouse Glass makes one think of Erich Kästner's first published book for children after World War 2, Konferenz der Tiere. But this summit's a much more sexed-up and mean-spirited version, because despite of Kästner's animals, who appear to have a greater willingness and capacity for peace compared to humankind, Haifisch's animals are mostly just interested in their own benefits, showing Haifisch's earlier faith in cute innocence – as it was propagated in The Artist and Von Spatz – ain't no longer an option in present times.

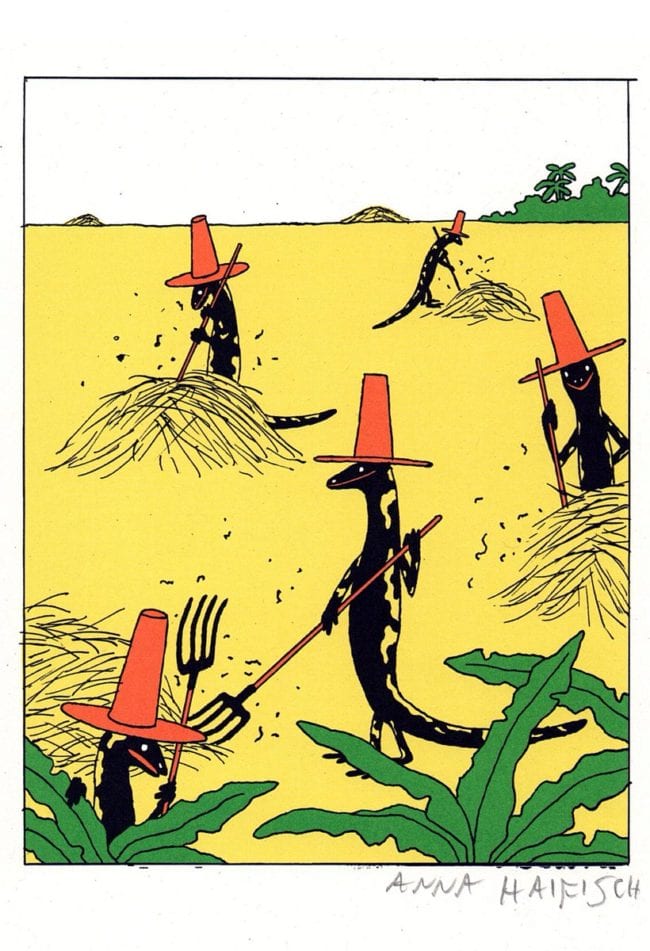

There are also scenes reminiscent of the merely three issues German illustrator Brigitte Smith did in 1972 for the Lurchi series, giveaway books from a children's shoe manufacturer named Salamander, that featured, you guess it, a salamander and his bunch of mainly anthropomorphic friends. The Smith issues turned out to be very psychedelic and pop-arty, lacking the racist tendencies often present in the remainder of the series. Smith is deemed a feminist and peace activist, and furthermore the first and very likely only woman to develop the series, who later was fired for not matching the readership's expectations. So it doesn't seem to be a coincidence that on the most beautiful page of Haifisch's book the salamanders are denounced as being orthodox and ticking time bombs by the summit's participants. But such is the spirit of the age.

There are also scenes reminiscent of the merely three issues German illustrator Brigitte Smith did in 1972 for the Lurchi series, giveaway books from a children's shoe manufacturer named Salamander, that featured, you guess it, a salamander and his bunch of mainly anthropomorphic friends. The Smith issues turned out to be very psychedelic and pop-arty, lacking the racist tendencies often present in the remainder of the series. Smith is deemed a feminist and peace activist, and furthermore the first and very likely only woman to develop the series, who later was fired for not matching the readership's expectations. So it doesn't seem to be a coincidence that on the most beautiful page of Haifisch's book the salamanders are denounced as being orthodox and ticking time bombs by the summit's participants. But such is the spirit of the age.