“Just…just get away from me! I don’t do that stuff anymore. I … I can’t. Leave me alone!” So says a prodigiously bearded, broken Allan Quatermain to his former partner in heroism, the gender-shifting Orlando, before running away. And later, to his ex-lover Mina Murray: “That’s all shit! All the adventuring … Th-that’s what’s fucked us all up, isn’t it?”

The promise inherent in all Moore’s work is also its peril. The meticulous, ostentatious authored-ness of his writing—a clockwork of references, symmetries, analogs and analogies—invites you do dig in and decipher, since there’s so obviously something to be dug into and deciphered. But only up to a point: Once you feel you’ve unearthed the “secret” of a particular Moore book, you might well stop digging. And by god, the exchanges above sure do feel like the point where you hit metal instead of dirt and say, “Guys, I think we’ve got something here,” as you toss your shovel aside. Though Quatermain has one more “L” and way less beard than the magus of Northampton, the resemblance is striking nonetheless, and the attitude toward the general field and specific genre in which he made his name unmistakable. And you know, if that’s all there is to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century: 2009 (I am going to miss writing out these titles, I tell you) — if it’s just Moore casting a harried, horrified look back over his shoulder at the world of comics and superheroes he revolutionized, then rejected, then was rejected by — that wouldn’t be so bad. It would, in fact, be fitting.

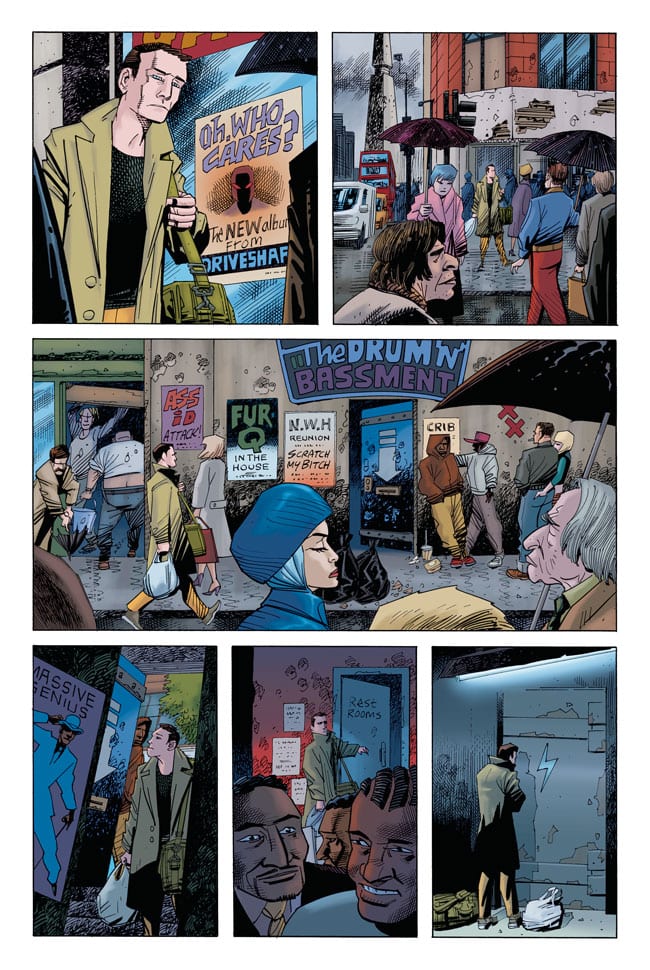

Moore’s oft-expressed, arguably oxymoronic, simultaneously held ignorance and contempt of contemporary entertainment leaves his stab at a post-millennial literary mash-up a much less comprehensive, more idiosyncratic venture than past installments of this long-running series. The events of the issue are dominated almost entirely by pastiches of the James Bond and Harry Potter franchises, both of which he reduces basically to bad jokes: The various movie Bonds are a series of replacement agents who’ve all aged in real time, up to and including a wheelchair-bound nonagenarian version kept alive by M (who’s also Emma Peel) as punishment for being a dick; Harry is the Antichrist, which discovery he celebrates by massacring everyone at Hogwarts before transforming into a giant with hundreds of eyeballs all over his body who shoots lightning out of his dick. Nods to the two TV shows Moore has admitted to watching over the past decade are almost disproportionately prominent: The fathers of half the cast of The Wire are the protagonists of the prose backup story, while the fellow who curses creatively in all those YouTube supercuts assembled from Armando Iannucci’s various enterprises does so here for two full pages. There’s a half-hearted stab at satire, maybe, in the form of a few shots at the fundamental conservatism and lack of ambition at the heart of J.K. Rowling’s fantasy franchise, but nothing Rowling ever wrote was half as dire, daft, or, Glycon help us, reactionary as “People were desperately poor in 1910, but at least they felt things had a purpose. How did culture fall apart in barely a hundred years?” This is something Moore makes Mina say, as though being assaulted by Dracula, the Invisible Man, and Lord Voldemort weren’t punishment enough. Aaron Sorkin, call your lawyer.

But despite its flabby, fallow bits … no, wait, that’s not the right way to put it. Its flabby, fallow bits are kind of the point. If any living comics creator has earned the right to end his epic with an “Uh, so the giant evil Harrychrist kills Allan Quatermain with electric piss, but then, I dunno, Mary Poppins shows up and kills the giant evil Harrychrist with her magic umbrella powers, something like that. Also she’s the Biblical God. Alright, see you later,” it’s Alan Moore. I like that League, potentially his final work in comics, ends with a shaggy-dog deus ex machina even woollier than Watchmen’s. I like that the final boss has all the menace of the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man (whom I’m a bit surprised has never made an appearance, actually). I like that the archvillain goes down with the same lackadaisical ease with which he defeated our heroes in the previous installment. I like that Moore’s primary response to a culture he finds baffling and dispiriting is to make corny jokes at the expense of the few bits he’s processed despite himself. I like that he uses that baffling, dispiriting tone to have Kevin O’Neill draw a visual symphony of wrinkly paunchy sad-eyed hatchet-faced people—it’s like having Ditko draw a comic about hand models who communicate using sign language. I like that they embody it by spending about as much time over the course of the issue depicting Orlando and later Mina futzing around her apartment doing various vulnerable things — showering, menstruating, pigging out on the couch while watching TV, having sex, snuggling, brushing the knots out of Mina’s scraggly hair — as they do showing the climactic battle. After the Wold Newton-style world-literature world-building of Black Dossier, the bloodbath of 1910, and the emotional catastrophe of 1969, it feels like creators and characters have earned their exhaustion.

It hounds Allan (spoiler alert!) right into the grave, poor chap, said grave being the final splash-page image of the book. On the verge of killing himself, the old adventurer finds he can’t pull the trigger, and decides to turn his wit and weapon against evil once again, and dies saving the people he loves. Mina’s words to her dying beloved are way too touching just to be a lampoon of what Jason Aaron once cried into his pillow: “Oh, Allan, Allan. Please don’t die. Y-you’re … you’re my … my hero.” There’s a whole world of grief and loss and self-discovery in that line, since after all it was Mina and Allan’s attempt to be in love without acknowledging that love means you lose your independence, that you need another person as badly as oxygen, that ultimately drove them apart, and mad, after decades of life together. But it does no good for Allan, just as one suspects the love and the need that comics has for Alan and vice versa will do no good for him either. We’ve looked down and shouted, “Save us!” and he’s looked up and whispered, “No.”