Would you like, reader, to have a profound and meaningful conversations about the utility and value of existentialism, the cheerily nihilistic philosophy for which we have to thank postwar French genius Jean-Paul Sartre? Sorry, we don’t do that sort of thing here. Instead, we’re going to ride that ever-reliable hobby horse best embodied by the classic question “Why is this a comic?”

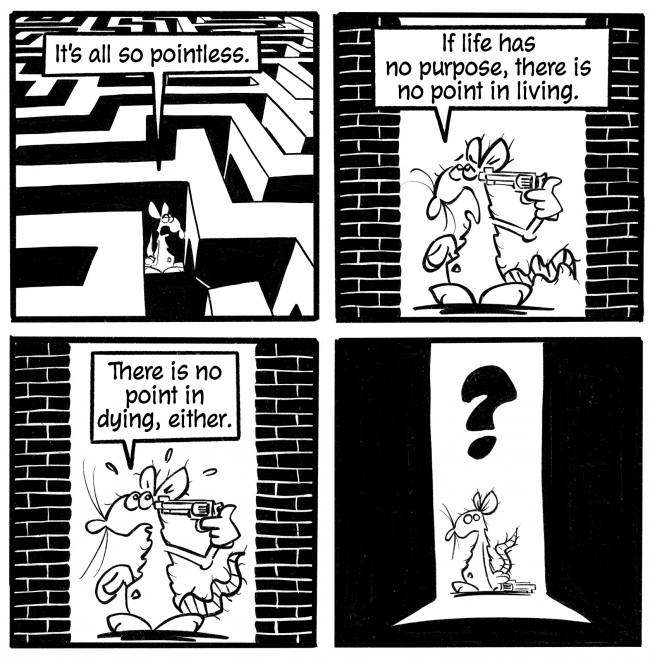

Why indeed. We can commence by talking about the quality of the book itself, which is…well, it’s not outstanding, but it’s too good to dislike. It’s fine, is what it is. The art, by Franco-Dutch cartoonist/capitalist Ben Argon, is actually very likable; he has a nice sensibility that reminds me a bit of Sergio Aragonés and a bit of Bill Amend, though far more hectic than the former and far more kinetic than the latter. Argon’s primary strength here is in his layout and design; using the visual conceit of two rats (one a dyed-in-the-pelt existentialist and the other a hapless normie) trapped in a self-imposed maze of the mind, he comes up with a lot of excellent compositions that bring home the strength of what he’s doing far better than most of the text, which ranges from mildly clever to perfunctory. The Labyrinth lives up to its name visually, if not structurally.

One might argue—and I think the publishers of this book would agree—that this is a good thing. Sartre was a popular philosopher to be sure, but existentialism is a metaphysical approach and can be notoriously thorny to work out, especially as embodied by Sartre in books like Being and Nothingness. Many readers will probably suss out the general contours of it much better when reading a book like The Labyrinth than they would crawling their way through the source material. Argon uses tried-and-true tactics of simplification, dialogue, and visual metaphor to deliver the central message of existentialism without the pitfalls of slogging through Sartre’s sometimes impenetrable prose.

Therein, unfortunately, likes part of the problem with the book. Philosophy, whatever you think of its practical value, is supposed to be difficult. It’s not about learning marketing tricks, or fixing a muffler, or even deciding who to vote for; it’s about the really big questions, like how we know what’s true and what isn’t, what the meaning of life is (if it even has one), or why we make the moral choices we make. A lot of those questions are contained in this very book, and it’s not to say that they’re in any way lessened or blunted by having them come out of the mouth of a cartoon rat; but sometimes you need to hear them from a grim-faced Frenchman who’s forcing you to pay very close attention in order to understand their import. These are, after all, pretty serious questions, and there’s a reason that one is encouraged to work it out for one’s self.

Therein, unfortunately, likes part of the problem with the book. Philosophy, whatever you think of its practical value, is supposed to be difficult. It’s not about learning marketing tricks, or fixing a muffler, or even deciding who to vote for; it’s about the really big questions, like how we know what’s true and what isn’t, what the meaning of life is (if it even has one), or why we make the moral choices we make. A lot of those questions are contained in this very book, and it’s not to say that they’re in any way lessened or blunted by having them come out of the mouth of a cartoon rat; but sometimes you need to hear them from a grim-faced Frenchman who’s forcing you to pay very close attention in order to understand their import. These are, after all, pretty serious questions, and there’s a reason that one is encouraged to work it out for one’s self.

This doesn’t always work; an anthropomorphic rodent may not be the ideal delivery vector for a lecture on existentialism, but try, for example, to read Kant and figure out what he’s trying to say beyond “I am Kant and I think highly of my own arguments”. It’s just that, well, this shit has stakes, is what I’m getting at. Does life have meaning? Does it make any difference what choices we make—and are we even really making choices? Does it matter if we just kill ourselves? These are not questions to be taken lightly; even Albert Camus knew that getting the wrong message about existentialism could lead to, for example, murdering an unnamed Arab man on a beach. And there’s nothing wrong with visual metaphors, either! It’s just that, by choosing an inherently frivolous form to deliver these ideas, Argon risks sacrificing import for accessibility—an ongoing risk in this subgenre of what are, in essence, educational aids. Again, not that there’s anything wrong with that! It’s just a very delicate balancing act, and the book—especially in the dialogue, which veers between poles of explicatory and pedantic, stopping a little too frequently to make a joke work—doesn’t always maintain that balance.

For all its inventiveness and engaging style, The Labyrinth is a variation on the huge spate of books that came out in the 2000s of the “[Pop Culture Phenomenon] and Philosophy” genre, wherein attempts were made to introduce casual readers to highbrow philosophical concepts through the lens of this or that currently popular movie or TV show. The problem with these books—and it’s a bit of a problem here as well—is that they put the cart before the horse, letting familiarity with the property or the medium drive the discussion rather than the other way around. This is somewhat of an unfair comparison, but the genius of Maus wasn’t that Spiegelman took the edge off of his Holocaust tale by using funny animals to tell it; it’s that he used the funny animals to draw the reader in and then emphasize and reinforce the savage inhumanity of it all. Argon takes the opposite approach here, and while it is and is meant to be more entertaining, it also loses a lot of the impact of Sartre’s ideas by extracting and diluting them.

For all its inventiveness and engaging style, The Labyrinth is a variation on the huge spate of books that came out in the 2000s of the “[Pop Culture Phenomenon] and Philosophy” genre, wherein attempts were made to introduce casual readers to highbrow philosophical concepts through the lens of this or that currently popular movie or TV show. The problem with these books—and it’s a bit of a problem here as well—is that they put the cart before the horse, letting familiarity with the property or the medium drive the discussion rather than the other way around. This is somewhat of an unfair comparison, but the genius of Maus wasn’t that Spiegelman took the edge off of his Holocaust tale by using funny animals to tell it; it’s that he used the funny animals to draw the reader in and then emphasize and reinforce the savage inhumanity of it all. Argon takes the opposite approach here, and while it is and is meant to be more entertaining, it also loses a lot of the impact of Sartre’s ideas by extracting and diluting them.

In writing this review, I worry I’ve been too unfair to The Labyrinth. Argus has good intentions, a satisfying concept, and skillful execution. Taken for what it is, and as an amplification for those who have read Sartre, or will be led to do so, it’s perfectly worthwhile. But it is not a standalone work; it is art build around another man’s work, and in this regard, it can seem a bit frivolous and mismatched, and therefore serve as a reduction rather than the interpretation or amplification it is clearly meant to be. Because it sometimes reads like the work of a gifted student, I can see it working like gangbusters as an academic accessory to scholars of Sartre, but as a popularization or a stand-alone work of art, it is more of a curiosity.