The G.N.B. Double C, or The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists, is perhaps Seth's strangest book to date. In terms of its spontaneity and sketchbook origin, it resembles Wimbledon Green, but it's also like George Sprott in its resolute Canadianness and lack of plot. It's mostly a work of fantasy as Seth takes the reader on a tour of the Dominion, Ontario branch of the G.N.B.C.C., a cartoonist's organization slash lodge that previously existed only in Seth's mind. Indeed, Dominion itself is another product of Seth's imagination as the setting for several of his comics. Seth apologizes to Dylan Horrocks for inadvertently biting his concept of the Hicksville lighthouse library, containing all of the great comics that were never published. Somewhat like Horrocks, Seth creates his own alternate history (of Canadian cartooning here), but there's an important emotional difference between Hickville and The G.N.B. Double C.

Unlike in Hicksville, where Horrocks uses the lighthouse library as a device representing all of the great comics that could have been (but were never published because of an apathetic industry), the fake cartoonists and comics Seth introduces in The G.N.B. Double C are frequently second-rate, uninspired, populist hacks and hackwork. Even in his own sketchbook fantasy, Seth can't quite commit to Canada as a land of comics milk and honey. Instead, the G.N.B.C.C. houses work and memories that represents a warts-and-all approach to the history of comics. A number of these previously popped up in Wimbledon Green and are emblematic of a certain kind of popular comic, like the Inuit astronaut Kao-Kuk or the gumball machine character Jocko. There's even a Fletcher Hanks-type cartoonist named Sol Gertzman who "drew" a bizarre character named Canada Jack, who was more mouthpiece for civic and philosophical issues than a superhero.

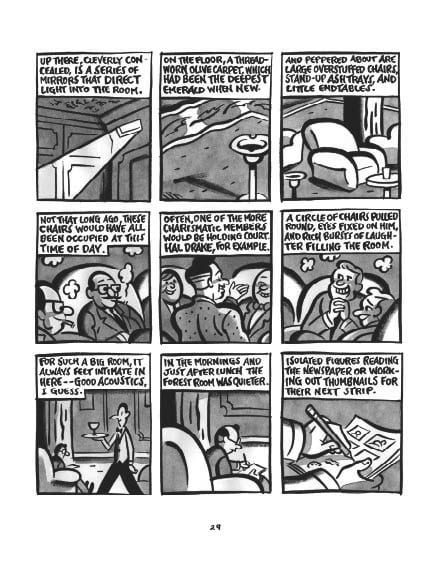

Seth does talk about the work of real cartoonist Doug Wright at length; this was his first such foray into publicizing the legacy of the Canadian cartoonist prior to the huge coffee table book and series of paperback reprints from D&Q. There are a few other Canadian cartoonists he discusses by name, like Jimmie Frise, Arch Dale, and Peter Whalley. The best parts of the book involve the most fanciful and unusual projects, like the icebound G.N.B.C.C. archive containing all sorts of rarities. Unlike the lodge, the archive has all of the good stuff: original art, rare comics (like a fake 18th century comic about a real general, done as a lampoon), and a fantasy setting for any comics researcher. One can imagine the late Bill Blackbeard having taken a trek up there and staying a season or two.

One of the more interesting side plots of this comic concerns the Journeyman award, the club's highest honor. Awarded just once per decade, to the best cartoonist of that period, only nine such honors have been "dealt." Some of the winners are invented, such as Isadore Lameque and a couple of others that I'll discuss in a moment. Others, like Frise, Whalley, Wright, and Chester Brown are real and represent the cream of Canadian cartooning. Intriguingly, Seth never names who won the 2000-2010 award (Dave Sim? David Collier? Julie Doucet? Seth himself?) nor does he name the winner from 1940-1950.

The winners from 1970-1980 and 1980-1990 are Seth's creations and deserve some mention. Henry Pefferlaw, winner in the first period, seems like an alter ego of sorts for Seth: a young, iconoclastic cartoonist who despised the status quo and who drew a strange work called The Great Machine that defies easy explanation. It's a vaguely sci-fi-tinged work of formalism that feels like a momentary exploration of an area of work that Seth perhaps has thought about pursuing. (Indeed, many of the characters and stories in this book feel like spitballed and tossed-off ideas that sound better on a sketchbook page than fully explicated in a major work). The winner from 1980-1990, Sam Middlesex, is Pefferlaw's opposite. He's an older man who came to cartooning late in his life, after a career as a barber, and then churned out volume after volume about the solemn life of a Canadian family. This seems to be a kind of commentary on Seth's own work, Clyde Fans in particular: "Narratively a bit staid. Even melodramatic in spots (though he stayed clear of soap opera )... he was no poet, yet he did manage to capture some sense of the profound."

Toward the end, Seth unravels much of his false narrative. He tells the reader that there really isn't a Mountie at the front of each clubhouse, and that cartoonists weren't really revered by the greater Canadian public. Again, even in his own work of fantasy, Seth throws some cold water on his own dreams. Perhaps this is a reaction to some criticisms of his masterwork, It's A Good Life If You Don't Weaken, which was so emotionally powerful and involved a mystery so engaging that many people thought it was a work of pure autobiography. If so, Seth may want the reader to doubt everything he is saying in this book to shake off a similar critique. In any case, Seth here certainly appears unwilling to glorify mediocrity, even if it has social or cultural significance—even if they're his own mediocre creations! I tend to favor this warts and all approach.

Perhaps the previous Seth work this most closely resembles is his Forty Cartoon Books of Interest, a small book of essays about frequently obscure and not always worthwhile collections of cartoons he'd come across in his lifelong hunt for unusual comics. There's a tension in Seth's work between being fascinated by comic-as-archival piece vs comic-as-art; there's a sense that he feels he must be wary of overvaluing the former when it doesn't measure up as the latter. That battle between nostalgic sentiment and discerning critical eye has always been at the heart of Seth's work, even if he at times doubts he's capable of making such a distinction in an objective manner. The G.N.B. Double C is a distillation of that conflict, and as such it's his most personal work--even if the personally revealing details are oblique.