Is there a more sadistic cartoonist working today than Nick Maandag?

I’ve been asking myself this question ever since Maandag’s self-published mini-comics first appeared on my radar more than a decade ago. In the years since, the Toronto-based cartoonist has unleashed a tidal wave of comedic misery on his luckless characters.

Whether it’s the embarrassment of public nudity (Streakers), the disgrace of abandoning your personal beliefs for sex (The Libertarian), the indignity of living with a brutish slob (The Oaf), or simply being forced to defecate at prescribed times of day by corporate lunatics (Facility Integrity), Maandag has earned a reputation for fashioning Grade A humor out of humiliation.

To be fair, over the course of his 11 comics he’s explored non-cringe humor, like the relationship tale of Jack and Mandy (2008) and Nick Maandag’s Laff Depot, a 2009 collection of short strips. But these felt like pit-stops for the cartoonist; palate cleansers that allowed him time to refine the merciless resolve that has become his calling card.

Now 12 years into his comics-making career I think it’s time to face facts: Maandag is at his best when his characters are at their worst.

Case in point: The Follies of Richard Wadsworth.

Clocking in at 150 pages, Wadsworth is his longest book to date (and his first for Drawn and Quarterly), and is comprised of three standalone stories, each populated with the kind of pompous stumblebums, demented weirdoes, and hapless dweebs that his readers have come to know, love, and expect. But while the characters are familiar, each tale ends up in a different (and sometimes darker) place. Thanks to this broader palate and more ambitious narratives, Wadsworth will likely satisfy long-time fans while welcoming new readers into the Maandag fold.

The title story stars Richard Wadsworth, a 37-year-old metaphysics instructor who is starting a teaching contract at a new university, the latest stop in his quest for academic tenure and the professional validation he believes he is long due. Wadsworth’s optimistic journey is plagued by mistaken identity, misplaced self-confidence, and a pilfered wheel of cheese.

“Night School” is set in a community college and features a demented fire chief who insinuates himself into a business administration course, where he unleashes mayhem, discipline, and wasps on the students he is presumably there to mentor. Almost Orwellian in design, the story takes many bizarre (and potentially allegorical) turns, before ending badly for all involved.

“Night School” is set in a community college and features a demented fire chief who insinuates himself into a business administration course, where he unleashes mayhem, discipline, and wasps on the students he is presumably there to mentor. Almost Orwellian in design, the story takes many bizarre (and potentially allegorical) turns, before ending badly for all involved.

The last story, “The Disciple,” takes place at a co-ed Buddhist monastery, where the fledgling monks struggle to balance their vows of chastity with their baser instincts. It also features Brother Bananas, a monkey (get it?) who thankfully amounts to more than just a punchline.

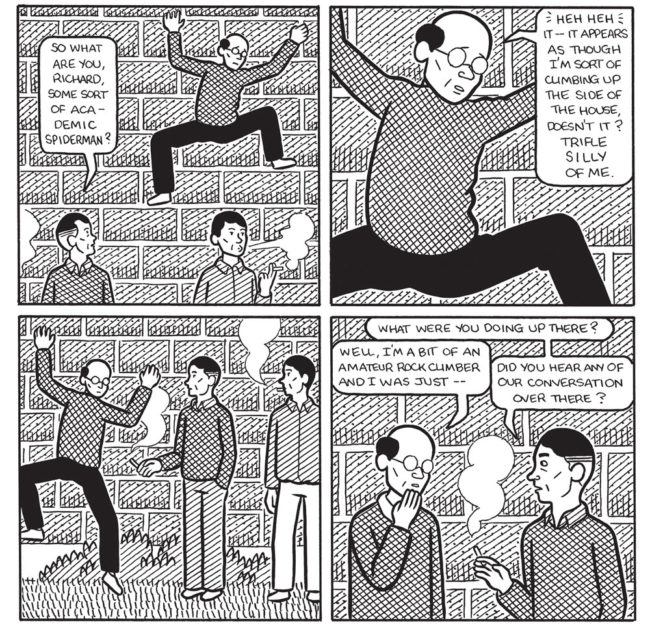

Each of these stories begin in familiar settings, and serve as perfect platforms for Maandag’s ace ability to set up and execute visual gags worthy of Keaton or Chaplin. There are plenty here to choose from, but Wadsworth’s awkward wall-climbing incident and his ill-advised visit to a massage parlor are squeamish standouts. It’s in these moments that Maandag’s cartooning chops really shine.

Though reviews of his work usually gloss over (or offer excuses for) his rigid, geometric style I think his deceptively spare art serves his brand of humor exceptionally well. And while Maandag’s art will always exist to service his writing, I noticed several “show-don’t-tell” moments in Wadsworth where a subtle change in facial expression delivered key plot points.

Though reviews of his work usually gloss over (or offer excuses for) his rigid, geometric style I think his deceptively spare art serves his brand of humor exceptionally well. And while Maandag’s art will always exist to service his writing, I noticed several “show-don’t-tell” moments in Wadsworth where a subtle change in facial expression delivered key plot points.

Unlike his previous works which tend to conclude on somewhat predictable punchlines, these stories end on notes of quiet contemplation, idle horror, and smug self-satisfaction. His characters still flail and fail to hilarious ends, but for some (like the titular Wadsworth) he grants them a refreshing and unexpected stay, and with it the possibility of hope.