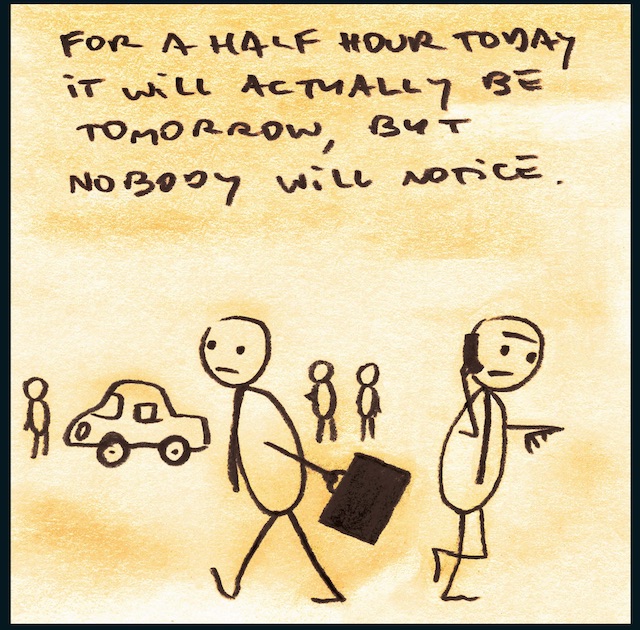

Six years after its initial publication by Antibookclub in 2013, Penguin Random House has re-released Don Hertzfeldt’s first graphic novel The End of the World. For those unfamiliar with the acclaimed animator’s only comic, The End of the World consists of a series of disconnected full-page panels depicting Hertzfeldt’s topsy turvy spin on the apocalypse. From a human clone on display in a museum to rock-stacking cannibals to some disembodied voice screaming “Mildred,” Hertzfeldt’s stick-figure drawings blend deadpan and dark humour to produce a vision of Armageddon fit to be the brainchild of Gary Larson and Friedrich Nietzsche. In this sense, graphic novel may be an inappropriate terminological choice by the book’s marketers given novel implies some form of narrative with a problem and resolution. In Hertzfeldt’s apocalypse, however, there is no problem or overarching plot, only wry suffering in a surreal and nihilistic world. For Hertzfeldt, that singular event marking the end of all stories is itself a non-story.

As is often the case, the “end of the world” here refers not to the destruction of planet Earth, but rather the end of human life on it. Thus, the “end of the world” actually signifies the end of any human perception of the world, and so, any narrative meant to interpret and understand the world. By opting out of any larger connective plot between individuals and events other than the broad idea of Armageddon, The End of the World portrays the apocalypse and human activity therein from a narratively non-anthropocentric viewpoint. Although Hertzfeldt’s new publisher describes the book as transcending “its unusual nature and tap[ping] into the deeply human, universal themes of mortality, identity, memory, loss, and parenthood,” The End of the World rather depicts a more non-human vision of the Anthropocene’s end, a narrative lens mirrored in the comic’s drawing style.

Hertzfeldt relates his deadpan apocalypse via stick figures drawn on Post-It notes, producing a backdrop-less, barebones aesthetic that advances the non-anthropocentrism implicit in his comic’s plotlessness. Through this stick figure style, the human actors of Hertzfeldt’s comic are alienated from the reader, defamiliarizing the reader with their own status as a human agent in the world and thereby aiding readers in viewing the world as it is apart from their human perspective. The encompassing vacuity of Hertzfeldt’s images stand as a palpable absence on the page leaving readers with that haunting suspicion that a similarly substantive emptiness surrounds their own existence. Here, in the contrast between the stick figure’s frail emulation of a human and the substantive nothingness of the surrounding page, readers glimpse the co-existence of being and non-being, thought and unthought, presence and absence, that constitutes the comics medium.

Hertzfeldt relates his deadpan apocalypse via stick figures drawn on Post-It notes, producing a backdrop-less, barebones aesthetic that advances the non-anthropocentrism implicit in his comic’s plotlessness. Through this stick figure style, the human actors of Hertzfeldt’s comic are alienated from the reader, defamiliarizing the reader with their own status as a human agent in the world and thereby aiding readers in viewing the world as it is apart from their human perspective. The encompassing vacuity of Hertzfeldt’s images stand as a palpable absence on the page leaving readers with that haunting suspicion that a similarly substantive emptiness surrounds their own existence. Here, in the contrast between the stick figure’s frail emulation of a human and the substantive nothingness of the surrounding page, readers glimpse the co-existence of being and non-being, thought and unthought, presence and absence, that constitutes the comics medium.

This fundamental dialectic to the comics medium approaches its visual peak on one of The End of the World’s last pages. On that page, the Post-It note drawing has been torn, leaving only a third of the image against an unrelenting black void. Here, an abysmal force crowds onto the panel, visually manifesting the actualization of a substantive non-being, and its extinguishment of being, that constitutes the end of the (human) world. For is not the apocalypse, the conclusion of the Anthropocene, the replacement of human-being with non-being? It is not the cessation of thought, but the triumph of unthought. So in this image, the panel-as-presence gives way to the gutter-as-absence as the pictorial boundary between being and non-being retreats from the latter’s rising strength until the image, like humanity, fades beneath a palpable and unfeeling Nothingness.

Of course, this nothingness has always been at the heart of reality, an idea played upon in another page of Hertzfeldt’s comic. Therein, three stick figures with arms raised surround and stared down upon an unknown entity beneath a caption in dialogue quotes that reads, “This is amazing! It explains everything!” But the Post-It note on which the image is drawn has been torn, forging a small abyss where the all-explaining object resides and thereby leaving the stick figures to rejoice over a gap. The Post-It’s tear alongside the characters’ proclamation produces the image of people reveling over the all-explaining power of absence. Nietzsche famously quipped that when one stares into the abyss, the abyss stares back. Here, three faceless figures gape into an abyss and neither wince nor cry aloud, but rejoice with arms raised in elation, for they see in it that which constitutes the heart of their nihilistic, a-logical universe. In this philosophically pessimistic comic, Hertzfeldt’s universe is characterized and permeated by an immanent absence where meaning would be present, so that Nothingness explains everything.

In any blurb or interview related to the End of the World’s previous or current publication, the fact inevitably arises that Hertzfeldt composed this comic from a series of Post-It notes he drew during late hours as notes for other story ideas. Finding that the hodgepodge pile of miscellaneous thoughts could be strung together by a conceptual link of the apocalypse, Hertzfeldt compiled The End of the World. This is precisely how the comic reads, as a series of unfinished and disjointed ideas. Normally, this would be a criticism, but Hertzfeldt has made it work through the matching of (non-)narrative and aesthetic. Personally, I doubt The End of the World will be crowned a classic, though its republication by a major publishing house suggests it resonates with a large demographic on some level, so perhaps time will prove me wrong. Either way, The End of the World is an enjoyable read. And if our world is as purposeless as the one Hertzfeldt imagines, people should cling to joy where they find it.

In any blurb or interview related to the End of the World’s previous or current publication, the fact inevitably arises that Hertzfeldt composed this comic from a series of Post-It notes he drew during late hours as notes for other story ideas. Finding that the hodgepodge pile of miscellaneous thoughts could be strung together by a conceptual link of the apocalypse, Hertzfeldt compiled The End of the World. This is precisely how the comic reads, as a series of unfinished and disjointed ideas. Normally, this would be a criticism, but Hertzfeldt has made it work through the matching of (non-)narrative and aesthetic. Personally, I doubt The End of the World will be crowned a classic, though its republication by a major publishing house suggests it resonates with a large demographic on some level, so perhaps time will prove me wrong. Either way, The End of the World is an enjoyable read. And if our world is as purposeless as the one Hertzfeldt imagines, people should cling to joy where they find it.