Originally published as a series of short minicomics through his own Oily Comics micropublishing concern, Chuck Forsman's The End Of The Fucking World (TEOTFW) is an incredibly assured full-length debut from an artist who's been making huge strides since graduating from the Center for Cartoon Studies. Given how many excellent minicomics he's made (especially in his Snake Oil series), I hesitate to call this book a "debut", yet for many it will be their first exposure to Forsman's work. Forsman's main storytelling interests revolve around the aimless, most especially teenagers as they react to their parents. He has a knack for giving voice to a certain sense of ennui and desperation for connection and meaning, yet manages to do so in a way that avoids navel-gazing and static storytelling. In some of his books, this involves adding a magical realist or fantasy element to create a different layer of storytelling. The heart of his stories remains the same, as Forsman is interested in examining the relationship between parents and children, especially when things have gone horribly wrong. When a child isn't loved or nurtured, how do they negotiate the world? What choices do they make? When they are on the cusp of adulthood, how do they react to their newfound sense of agency and power? These are the questions that form the backbone of TEOTFW.

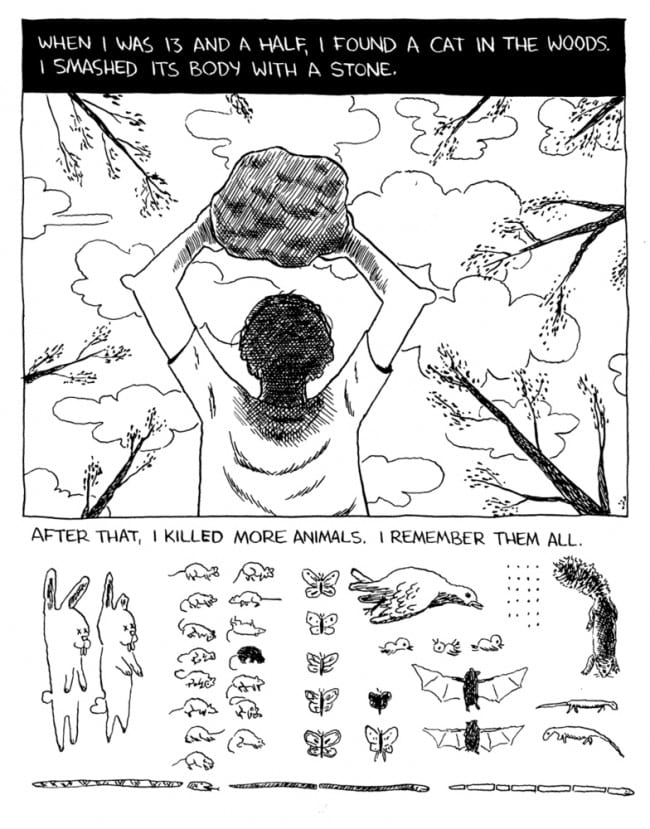

In TEOTFW, Forsman turns teen angst into a road trip that winds up having very real stakes. We are introduced to James and his girlfriend Alyssa, and the characters alternate narrating each chapter. It's a simple but effective decision that never lets the reader linger too long on a particular point of view and one that reminds them that there's no simple perspective on what's happening in this story. James is a young sociopath who kills animals and hurts himself simply in an effort to feel something, anything. Alyssa is drawn to him precisely because he's a huge void of emotion, a quiet presence that she mistakes for strength and security. In some ways, his narrative reminds me a little of Travis Bickle's in Martin Scorsese's film Taxi Driver. Bickle is an aimless, alienated sociopath looking for an appropriate target to vent his uncontrollable rage after being rejected by the girl of his dreams. James is an introverted and younger version of Bickle, but both wind up channeling their willingness and interest in killing into something that approaches the heroic. The difference is a matter of agency, though in both cases there are moments where a simple whim decides their course.

The difference between the two is that James reveals a sense of awareness that there's something very wrong with the way he is. He wants to be able to feel, and a series of plot twists give him a set of choices that wind up making him a hero, albeit one who is largely vilified by others. However, the key sequence in the book comes early, when he thinks about strangling Alyssa: "Instead, I took a breath and tried once more to let her in." This one sequence lets the reader know that something happened to traumatize James, but that there is still some vestigial humanity left inside of him. Forsman reveals that trauma in James's matter-of-fact, affect-free manner later in the book, and it serves to further allow the reader to sympathize with James even as it's difficult to fully embrace him.

Indeed, making half of the book take place from Alyssa's point of view heightens that very difficulty, as the reader is constantly on edge regarding this couple. She's a typical rebellious teen who at least has a home, even if it's far from ideal, as her father left years earlier. The quest to find him that makes up much of the book's plot really serves as a way for her to fully reject what her mother represents to her: boredom, indifference, oppression. James acts as a kind of blank slate for her to mold and even push around after he punches his abusive father and steals his car. Very quickly, the reader understands that her aggressive attitude masks fear, but both teens have the feeling that they've crossed a line and can only keep going as far as they can at this point.

When the couple finds an empty house owned by a rich man on vacation, it represents their utopian vision of what their lives could be like together. Despite the fact that both have feral qualities (cleverly depicted by Forsman in the way he draws them as generally shaggy, unkempt, and animalistic when they raid the kitchen of the house), living in the house is a way of living out their dreams of being together. James notably says that it gives him a feeling of being in control for the first time, and there's no doubt that that lack of control drives his sociopathic tendencies. This is where Forsman introduces the plot contrivance of the owner of the house being a satanist who ritually murders young women, and James hits upon the plan of murdering him.

While the twist is a bit on the ridiculous side, it's really a kind of mcguffin that launches James into acting rather than reacting. It also gives the book a needed jolt and propels the back half of the book, as we see the man's police-officer wife track James across the country. Of course, she quickly reveals that she's not what she seems either. Indeed, their ritualized violence and double-lives make them a kind of mirror version of James and Alyssa, and one gets the sense that James seeks bloody and righteous justice, more as a way to punish them for their deception (and the deceit of all adults) than for their actual crimes. They are brutal killers who are rich (the man) and powerful (the woman, who literally embodies the law), and in some sense they are a teenage fantasy of adult hypocrisy writ large. Not every adult in this book is a hypocrite or liar (Alyssa gets some help from a sympathetic security guard), but every meaningful authority figure in the book is a liar, hypocrite, or killer. Forsman leaves open the question as to whether James is willing to sacrifice himself because he thinks so little of his own life or because he values Alyssa's so much, but the evidence tips toward a combination of the two. James has pinned Alyssa as his only hope to be human, to feel something for someone else, and that's just what happens. The sequence where Alyssa briefly leaves him points to this, as he's beaten up by some thugs; James understands that Alyssa is really his "protector" in that she's the only thing that gives structure and meaning to his life.

Forsman's drawing style is simple, gritty, and basic. His character designs, always strongly influenced by comic strips, remind me a lot of Dik Browne's Hi and Lois, of all things. There are dots for eyes, hair obscuring faces, simple noses, and lots of shots of characters in profile. Even the drawings of dead animals have little x's over their eyes, giving the whole book a weird quality of a kid's story gone horribly awry. The approach also allows the reader to project and relate to the characters more readily than a naturalistic style might have while not reducing the shock of the book's more violent scenes. This is Forsman's longest sustained narrative, and it never flags. Originally releasing each minicomic in short bursts added to that sense of punch in each chapter, as Forsman no doubt felt compelled to make each individual issue of interest. The spareness of the drawings allows Forsman to really concentrate on the relationship between James and Alyssa, and it's a tribute to his skill that he's able to tell so much of the story through their body language and how they relate to each other in space. The slumping shoulders, rolled eyes, and physical comfort they feel in each other's presence are rendered simply and gracefully by Forsman; there are simply no extraneous lines to be found in this comic. That's a mark of a confident artist hitting his stride, and TEOTFW feels like Forsman's comics PhD project.