There are different kinds of silence. There is peaceful quiet and there’s eerie stillness, and while the former is conducive to reading, the latter could mean listening too intently for what might soon intrude to pay attention to what’s before one’s eyes. A comic generally gets called “silent” when reading it entails following images alone, without any dialogue or narration providing guideposts of written language. While there are extended passages of The Cult of the Ibis where the story is told purely visually, there’s enough words in it that anyone translating it into another language would still have their work cut out for them. I see a different silence in it. It’s a signifier, referring to the earliest years of cinema, similar to the films of Guy Maddin that approximate a fever dream of forgotten history more than they attempt recreation or adaptation.

The plot contains a mixture of genres at home in early film: After a bank robbery goes wrong, the getaway driver is in possession of the stolen loot. Other criminals want this money back. However, before considering this possibility, the getaway driver, interested in the occult, sends away for a build-your-own-homunculus kit, after seeing an ad in a magazine The Modern Alchemist Monthly. In silent or early sound films, both crime stories and occult skulduggery would be a a likely premise for a fable of moral reckoning, but that’s not what happens here. Daria Tessler understands that the reason movies were made about these subjects as soon as movies existed is because magic and bank robbery are cool and interesting to think about, and there is no better way to meditate on a concept than the time-consuming process of making narrative images about it.

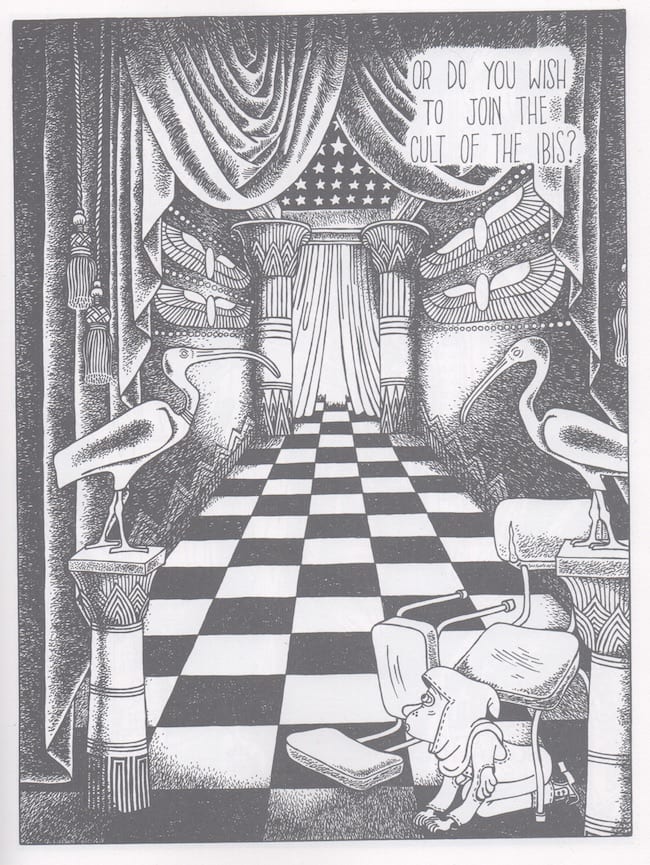

In The Cult of the Ibis, those images frequently take over entire pages, an approach reminiscent of children’s books, creating a parallel between an early reader’s developing consciousness and the development of recording technologies for the book to occupy a space between. Tessler is a prolific printmaker, and when working in that medium, she regularly features multiple layers of colors intersecting to astounding textural effect, creating otherworldly landscapes of soft psychedelia similar to the Eastern European children’s book illustrations viewable at 50 Watts. Here she works in black and white, and when her pages do have multiple panels, they are often in odd compositions that you take in as a whole, rather than read strictly sequentially.

Tessler’s drawings are funny, but also moody and maybe even terrifying, depending on a reader’s sensitivity. Her shapes suggest one thing and her textures another. I can’t say this stuff isn’t cute, but it’s more wooly than fuzzy. It’s not soft to the touch; running fingers through it would find many clumps of matted fur. The composition of pages ask you to inspect the images for detail, and after your eye circles the center repeatedly and follows lines through it, it then stops to look again at the whole, as if the brain has caught it in the act of drawing mystic symbols, guided along by discreetly hidden methods. Details add an expressionist character to the background of each page and imbue the building of its world with a peculiarly shambling sense of architecture. I love the little detail that what looks like a TV in the main character’s home is actually a fish tank. This is the sort of visual gag of a design choice that suggests the larger fictional world is built around preferences that carry ideological connotations. While we recognize the shape of this world, there’s still a suggestion that television does not exist in it, though this is later undercut when working televisions appear.

The absence of the internet remains implied. The world of the book reflects a nostalgia for a 1990s landscape of zines and mail-order catalogs. This was a method of communication that allowed for the esoteric and occult to be hidden from view, away from the prying eyes of mass media and hyperlinks. While the idea of a magazine about alchemy might scan as a gag, from a 2019 perspective both interest and medium feel similarly musty. Focusing on these things reinforces this atmosphere, which feels like a relic of the early twentieth century, and then recasts it in its image. Black-and-white is the shared visual language of cheap xeroxes and the luxurious production of a Fritz Lang epic, and Tessler’s alchemy reconciles these opposites into a single thing. When we see pages of the Modern Alchemist Monthly, they appear like intertitles, albeit with far more text, for the pace of a book allows them to be dwelled on and returned to where a film would only want to limit the amount of reading a viewer would do at any one moment to keep the pace brisk. Eight consecutive pages are inserted into the book around the time a reader might expect a climax to be approaching. This is frustrating, but the allocation of space to pages of text in a comic that’s mostly wordless places a premium on the old-fashioned value of reading, in contrast to a fast-moving and superficial culture.

By that point we have already begun to move away from structured, plot-oriented storytelling in pursuit of something more dreamlike. About halfway through the book, our main character finds a key inside a banana. This development might not feel like a natural progression from the beginning of the book, but it is in keeping with how you’ve read it. Most pages don't so much read from left to right as they emanate and revolve around their centers organically. If each image feels like a sweet fruit you peel the skin back from and sense a hidden compositional principle, then the discovery of such a key is seemingly presaged. Still, that moment marks a turning point, where the narrative’s logic begins to devolve into something less beholden to the rules you might expect it to play by. The money has already been spent mail-ordering the build-your-own-golem kit, and later one appears in a motel vending machine. These things move the narrative along, in a way: The residence where she ordered the kit had to be abandoned as pursuers knew where she was, but there is also a feeling that the narrative as we understood it might be dissolving into mist.

Enough mystery and tension is built up in the unfolding of the first hundred pages that the question of “when are they gonna join the cult of the Ibis?” lurking in the back of the mind suggests something revelatory when the meaning of the title arrives. The title does figure into the story, though what it means is unclear. The book is in keeping with a lot of art comics whose initial pages develop a plot based around aesthetic interests that the author is then not particularly interested in resolving. Chris Cilla’s graphic novel The Heavy Hand is maybe my go-to example of a book that initially seems deserving of a wide audience but ends in a way where I would recommend it to the initiated only. However, for something so invested in magic hidden from mainstream society, “only for the initiated” is far from a diss.

The title is perhaps understood less as a plot point to await than as a state of mind to enter the book with: The ibis is a bird capable of flight that spends most of its time wading in water. It’s not evolutionarily backwards, it’s adept at hunting for fish. The opening of the book would be an ibis in flight, effortless-seeming forward movement, though the bulk of the book is dedicated to wading in something murkier and more reflective. Cult members appreciate this decision. They’re not as simple-minded as the sun-worshippers, for instance, who demand demonstrations of power with clockwork reliability to earn their continued praise.

You might already be a member of the cult; you may have been indoctrinated with its teachings at a young age. There is much in the book that reminds me of more accessible work. There’s a clockwork band reminiscent of the inflatable band in the Vincent Price movie The Abominable Dr. Phibes, backed by an off-stage phonograph reminiscent of the Cafe Silencio scene in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. There’s similarities in subject matter to the comics of Richard Sala and a design sensibility comparable to Theo Ellsworth. Much of the book’s gestalt is shared with a reference point so popular it has maybe by this point gained so many negative associations it’s not worth mentioning: Tim Burton. If your tastes could be summarized as “weird stuff” by your peers since before adolescence, it should be easy to take the parts of the book that are confusing or unsatisfying in stride. The ending may be anticlimactic, but readers of a certain age will already be familiar with the form of silence that might in the end be the book’s most appropriate point of comparison, from CDs in the '90s, when minutes would pass after the last listed song, suggesting a conclusive ending had been reached, before a jarring leap into audio with the anticlimax of an additional song, the secret hidden track.