Well, it’s that time of year again. The time when a witchy wind starts blowing and the darkness comes earlier each day, and it’s a little easier than usual to believe in magic.

Ron Regé, Jr. certainly seems to believe that magic is real, anyway — the good kind, at least. What is it called? White magic.

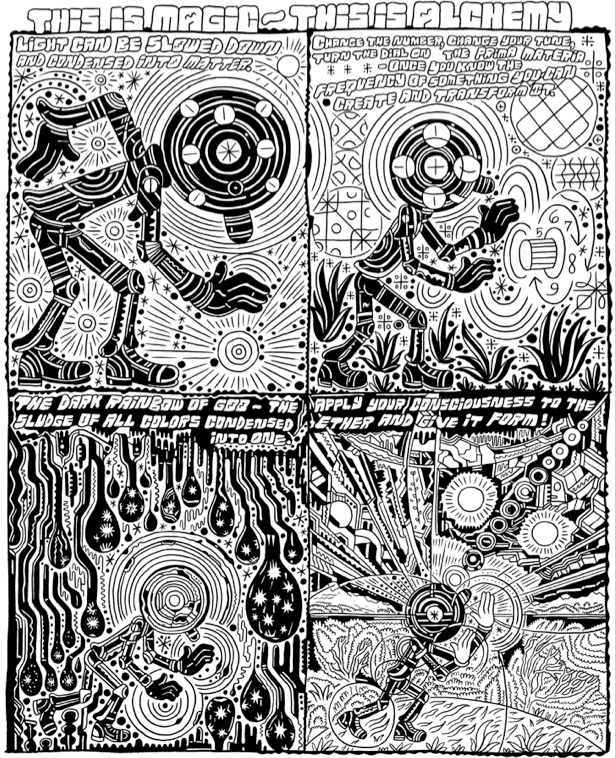

The comics in his new, almost literally dizzying book, The Cartoon Utopia, are packed with visual detail and collect his thoughts on magic in some of its many incarnations: astrology, the occult, sex magic, the “alchemy” of love relationships and other hermetic principles, and communion with animals. It opens with a short introduction by Maja D’Aoust, the self-described White Witch of L.A. who had Regé as a student in her “Magic School” lectures. In it, she describes the otherworldly sense of coincidence that swirled around the group of artists and musicians that took her class during this time.

“So, as you read the concepts contained within the passages of this tremendous work of art, take care, for the utterance of the magic words and their penetration into your eyeballs shall bring the magic to your life as well, and surround your heart — above, below and always,” D’Aoust writes. So right off the bat you know what you’re getting into.

Utopia loosely depicts a race of humanlike creatures of a future world who are as cute yet no-nonsense as Megan Kelso’s Artichoke folks. They go about their business, being gentle and wide-eyed, and occasionally reflect on “the time before people believed in peace” (i.e., now). But rather than following any narrative, the book depicts one psychedelic philosophy after another, breaking the ideas down and explaining them, sort of. Some of these seem to be Regé’s own, some have been pulled directly from his apparently limitless reading, and they’re all brought to life by his disarmingly simple and hippie-ish figures, all almond eyes and flowing hair.

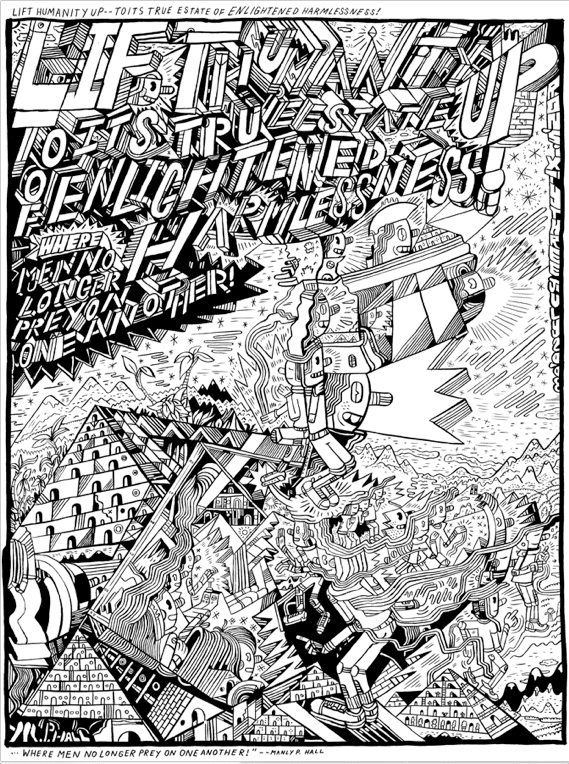

Anyone familiar with Regé’s previous comics will likely see this as a move toward something ... more difficult. Packed even tighter with detail and captioned in hard-to-decipher block letters, the visuals are squirrelly but orderly, almost obsessively so. In fact, in its alarming density the work has a needs-must quality that I find so intriguing, as if the drawings were made by a fringe artist in a fever to get his ideas out there but with limited access to materials. Almost impossible to categorize, the work in Cartoon Utopia is both fully realized in a formal sense and wonderfully idiosyncratic. Like, it’s really out there.

“The old patterns of culture are breaking up!” Regé warns us early on. “The new patterns are being formed!” He depicts the difficult and forward-thinking philosophies he admires; some of the people quoted include Blake, Goethe, Alan Watts, Manly P. Hall — all of them mystics as much as writers, artists and thinkers. He’s interested in the nature of the universe and our interaction with it (i.e., magic): “Light can be slowed down and condensed into matter. Change the number, change your tune, turn the dial on the Prima Materia — once you know the frequency of something you can create and transform it. ... Apply your consciousness to the ether and give it form.” He also deals with the inherent mysticism of animals, and the way we (can, but rarely do) relate to them: “You can share your consciousness with anything because we are all one thing.” Much of the book reads like this, a recitation of beliefs that makes the work feel something like a textbook or even a prayer book.

But to me the work is much stronger when it depicts magic in action, which Regé accomplishes by telling us stories about historical figures and their relationship to the natural world. Unfortunately, there are only a handful of these: There’s the tale of coincidence regarding Jung, a young client of his, and a scarab beetle; the piece about Tesla and the deep connection between his life’s work and a pigeon of his acquaintance; and my favorite, the moving story of Mesmer and his companion canary, who followed him everywhere and died within moments of Mesmer’s own passing. All of these passages accomplish Regé’s apparent goal of teaching us something about magic, and they require much less head-scratching to figure out.

But to me the work is much stronger when it depicts magic in action, which Regé accomplishes by telling us stories about historical figures and their relationship to the natural world. Unfortunately, there are only a handful of these: There’s the tale of coincidence regarding Jung, a young client of his, and a scarab beetle; the piece about Tesla and the deep connection between his life’s work and a pigeon of his acquaintance; and my favorite, the moving story of Mesmer and his companion canary, who followed him everywhere and died within moments of Mesmer’s own passing. All of these passages accomplish Regé’s apparent goal of teaching us something about magic, and they require much less head-scratching to figure out.

It’s also sweet when he gets personal, as he sort of does by telling little anecdotes about Sun Ra and talking about music in general. “All creative art is music!” he proclaims, and whether or not you know he’s a musician — Regé plays drums in the exuberant freak folk act Lavender Diamond — the declaration seems to carry more weight than some of his others.

***

Most of the text in Utopia is interwoven with its drawings, and it’s rendered in a cramped and uniform way that makes it difficult to read or even pick out from the surrounding art. This has the interesting effect of making the experience feel more like deciphering than reading, as if we’ve discovered an ancient holy book or are coaxing forth meaning from patterns in the natural world. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the book itself is like a magical thing, and reading it calls to mind the ideas of divination and conjuring.

Picking my way through the comic’s strange trains of thought, I was put to mind of the work of self-taught artist Justin Duerr, who has been making his quasi-spiritual, apocalyptic art zine Decades of Confusion Feed the Insect — in the old-school, photocopied style — for some fifteen years. His work, too, is crammed with vertiginous detail and prophetic writings, and also has an essentially hopeful message. A longtime, beloved member of the underground art scene in Philadelphia, Duerr has recently achieved wider acclaim for his documentary film Resurrect Dead, which is in turn about the really outsider artist behind the Toynbee Tiles, a street art project that makes oblique references to shamanism, government conspiracies, and life on Jupiter.

Picking my way through the comic’s strange trains of thought, I was put to mind of the work of self-taught artist Justin Duerr, who has been making his quasi-spiritual, apocalyptic art zine Decades of Confusion Feed the Insect — in the old-school, photocopied style — for some fifteen years. His work, too, is crammed with vertiginous detail and prophetic writings, and also has an essentially hopeful message. A longtime, beloved member of the underground art scene in Philadelphia, Duerr has recently achieved wider acclaim for his documentary film Resurrect Dead, which is in turn about the really outsider artist behind the Toynbee Tiles, a street art project that makes oblique references to shamanism, government conspiracies, and life on Jupiter.

All this to say: Some of The Cartoon Utopia reads like the loony but often prescient ravings of a madman-prophet, the kind you’re sometimes treated to on the subway. I guess that sounds insulting, but I don’t mean it that way. Those moments of authenticity and surprise — the joyful and unsettling shake-up of the everyday — are among the things I find most exciting in life, and Regé’s work teems with them, breaking down the expected order of things with the intention of installing a new one. I’m reminded of a quotation from Death By Black Hole by everybody’s favorite astrophysicist, Neil deGrasse Tyson: “One thing is for certain: the more profoundly baffled you have been in your life, the more open your mind becomes to new ideas.” Consider me baffled, but in a good way.

If you’re a mere mortal like me, you may need to read this book in small installments rather than attempting to cram it into your brain in one straight shot. Treat it instead like the religious text that it almost is, and school yourself over time.