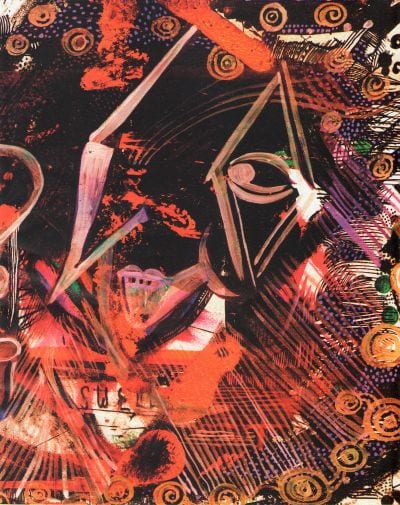

It can be a bit daunting to engage with these sorts of comics; they demand that you accept them on their own terms or not at all. They can be difficult to adjust to as a reader. But once a reader has locked into this style, the stories become impossible to put down. It doesn't hurt that Juliacks has excellent compositional chops as a cartoonist, seamlessly assembling a number of complicated images on each page. Her figure drawing is simple and usually displays a somewhat primitivist technique, but it's not unusual to see her go a bit more abstract in her character representations. Juliacks stuffs every one of her pages with powerful imagery, drowning the reader in drawings intended both as information and decoration (and frequently designed to do both). Trying to process that much information on a page (especially when the eye is not led to value one image over another) can be draining as a reader, and Juliacks often goes over the top in jamming her pages to the brim. Still, one can sense the raw energy and excitement present in her comics, and the level of detail certainly rewards repeated readings.

While Juliacks' comics are certainly self-contained entities, it's interesting to note that she's very much a multimedia artist. In fact, she often adapts her comics into performance art, or perhaps it is more accurate to say that both comics and performance art are different outlets and manifestations for the expression of her ideas. The themes are all the same, but the experience of the pieces themselves couldn't be any more different. Her live performances are built on a series of explosive moments instead of the more static experience of the page. If Juliacks' comics are the equivalent of being submerged in her ideas, her performance pieces are like having those themes splashed in one's face. It's fascinating to see a cartoonist reaching out to a live audience in such a way, achieving a sort of immediacy of reaction that is lacking in comics. These performances can be viewed on her website, but I'm guessing those clips fail to capture the visceral qualities of an actual live performance seen in person. What is obvious is the way Juliacks is able to completely rework her ideas into something that takes advantage of a live performance. The clips of her are kinetic, even frenzied, emphasizing body and movement on the stage as a complement to the way she exaggerates emotion on the page with her figure drawing and decorative flourishes.

Invisible Forces is both a comic and a film, and both are a bit colder and more removed than her other, more emotionally distant comics. This only makes sense, given that the story is about a young woman named Rody Plane whose life consists of one alienating, traumatic moment after another whose mind snaps in and out of contact with reality thanks to the assault of those titular "invisible forces." Juliacks likes working big, and the 12x7 pages on heavy paper stock contribute to the powerful visual impact of each page, especially given the bright and powerful color choices. That color and the extensive use of negative space is unusual for one of her comics and speaks to the hallucinatory nature of this comic, as Rody goes from staying with her father to working in an insane asylum to living in a hut. The galvanizing conflict for her is the feeling of paralysis in the face of the infinite. Simply comparing herself to the infinite is enough to freeze her in her tracks, much less the the experience of being in an asylum or living in the dark woods. In the end, she only survives by experiencing total disassociation.

Swell is a comic that has been adapted into a play/performance art piece and art installation. It's about a woman in her first year of college who is forced to attempt to cope with the sudden death of her older sister. Juliacks works big here, working at about 10 x 10". What's most striking about these comics is how advanced Juliacks' sense of composition is. There's a page where the story's protagonist, Emmeline, recalls an instance where her older sister, Lucy, smashed a bunch of eggs that Emmeline and her friends had decorated. There are decorative touches framing the page in the form of little eggs, and the panels are framed so as to form an egg. Juliacks changes her approach to a page at a frequently breakneck pace--going from a number of tiny panels in a row to huge splash pages.

The second chapter introduces us to Emmeline's parents, who are equally at a loss to process Lucy's death. Juliacks drops hints that Lucy had some kind of mental affliction or processing disorder, judging by the awkwardness she felt in social situations and her general neuroses. This first part of this chapter finds the grieving family trying to sleep and struggling to do so. They all wind up "dreaming awake." Juliacks introduces each segment with a huge splash page depicting one of the individual characters with a decorated egg-shape in his or her mouth that indicates she is dreaming awake. The next page is jam-packed with panels detailing each character's fears, hallucinations and neuroses, switching between an omniscient narrator and first-person stream-of-consciousness narration. It's occasionally a bumpy ride in a narrative sense, but Juliacks has a firm hand and never loses control of the page. When a sleepless Emmeline runs away, that throws her parents even further into panic and paralysis, even as Emmeline feels like she's moving toward some kind of resolution.

The second half of the book finds Emmeline wandering around the cemetery near her family's home, her lack of sleep creating a hallucinatory state of mind that in part fuels the grief ritual that she creates on the fly. Above all else, Swell is about the ways in which grief is a powerful emotion that can never be denied--only delayed. And that delay only leads to either madness or an inability to feel anything. Juliacks' captures that madness in Emmeline, as the rituals she concocts to remember and connect with her frequently difficult sister eventually allow her to journey back to sanity, but only after a harrowing journey. In the meantime, her parents simply clamp up, as they worry that they may well have lost two daughters. There's a great sequence where the father drives around the driveway in a looping pattern to make himself feel better, even as he relives a childhood trauma.

The back half of the comic is murky and dense, and the cheap newsprint doesn't do the heavy use of blacks any favors. I found myself wishing for a fancy hardback version with thicker, glossier paper that really showed off Juliacks' mastery over every aspect of the page. Still, her cartoony and sometimes abstracted character design, her use of decorative drawings to reinforce other images and ideas on the page, and the way she modulates emotion by varying panel and letter size lend this comic a tremendous amount of impact. She's part of a group of artists that moves with relative ease between the world of comics and the fine art world, helping to redefine how we think about both.