In 2011, Fantagraphics published editor Matthias Wievel’s Kolor Klimax, a very good anthology that introduced American audiences to Nordic comics artists. In that same vein, the company now offers up Spanish Fever, a Whitman’s Sampler of (you guessed it) Spanish comics edited by Santiago Garcia, with an introduction by Eddie Campbell.

The talent roster in Spanish Fever ranges from well-known pros like Miguel Gallardo and Max, to newer artists like Ana Galvañ and Clara-Tanit Arqué. There’s a wide variety of narrative and visual styles, ranging from traditional underground comix to the ubiquitous European “big nose" style to work that would look at home in an American minicomic. In subject matter, the stories range from autobiographical, political, and quotidian to surreal and just flat-out weird. It’s an eclectic stew that comes together agreeably, making a good case for the vibrancy of the Spanish comics scene, though a few weaknesses keep it from being a truly top-notch compendium.

In his introduction, Eddie Campbell notes that the new Spanish comics all share the importance of authorial voice, i.e., that they feature characters that are pure expressions of the authors, beholden to no meddling publishers or corporations. Garcia’s forward to the collection extrapolates on this theme, offering a mini-history of Spain’s comics leading to its current artistic renaissance amid the country’s current economic crisis.

Spanish Fever kicks off with Juano Sáez’s two-page “Adult Comics: The Graphic Novel”, which acts as the book’s manifesto. In this simply drawn prelude, Sáez speaks collectively of the artists featured, declaring, “We’ve read comics forever. We grew up and didn’t leave them behind […] And now we make the comics we want to read. Adult comics because we’re adults.” Apropos of that, we then segue into a collaboration between writer Antonio Altarriba and artist Kim called “The House of the Rising Sun”, a lushly illustrated, mildly erotic story of an innocent nubile who runs afoul of a love ‘em and leave ‘em cad, and ends up pregnant. In contrast to much of the rest of the book’s kaleidoscopic range of visuals, Kim’s artwork for this piece is rather traditional and realistic.

Some of the best pieces left me wanting more. Rayco Pulido’s “Great Grandparents” delivers a scant seven pages of what is apparently a series “dedicated to the imaginary Fundador family,” but Pulido’s scintillatingly geometric patterns and angular characters are a delight to the eye, and I would most definitely like to see more from this artist. A comic rendered with a similar sense of rhythmic, exacting linework is José Domingos’ “Number 2 Has Been Murdered”—also one of the funniest stories in the book. In it, a businessman reveals to his partners—comically, through charades—how another partner has met his demise. Domingo’s line is full of energy and I’m betting he had a lot of fun drawing this little confection.

Meanwhile, on the political side of the spectrum, the best entry is Paco Roca’s “Chronicle of a Crisis Foretold”, which dissects the disastrous results of unregulated capitalist greed upon the economies of Spain and the EU. Like Darryl Cunningham’s fact-based 2014 graphic nonfiction book, The Age of Selfishness (Abrams, 2015), Roca’s piece successfully conveys outrage and issues a plea (likely futile) for the sensible management of future financial markets.

In the “weird” storytelling vein there’s “Melted” by Álvaro Ortiz, which sets up an intriguing Twilight Zone-style scenario of a man who steals the wallet of another man who has mysteriously met his demise by literally melting away in public “like a fucking pistachio ice cream cone!” The story boasts a mounting sense of unease: we wonder when or if, due to his thievery, the protagonist will meet the same fate as his inadvertent benefactor. But the narrative veers from its initial origins into a realm that seems to have little to do with what came before. Ortiz may have been trying to establish a metaphor about disintegration and regeneration, but the two halves of the story didn’t quite connect satisfyingly.

There are some good autobiographical pieces. They range from the charmingly Feifferesque line scrawlings of Fermín Solís, starring his “Little Martín” alter ego, to Miguel Gallardo’s “Christmas at Home,” a brief but moving meditation on family ties that endure despite the inevitable conflicts and tragedies of life. Meanwhile, in “Writers Never Score”, Ramón Boldú relates an amusing tale of trying to make time with a gorgeous model who posed for photographers at a “nudie mag” where he worked in the '70s—the title telegraphs the reward for his efforts.

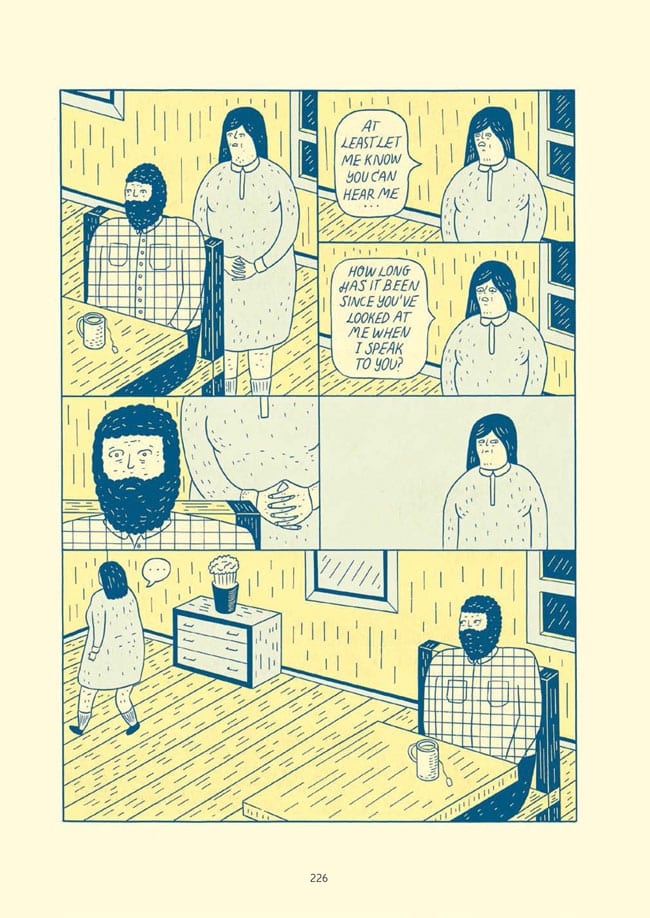

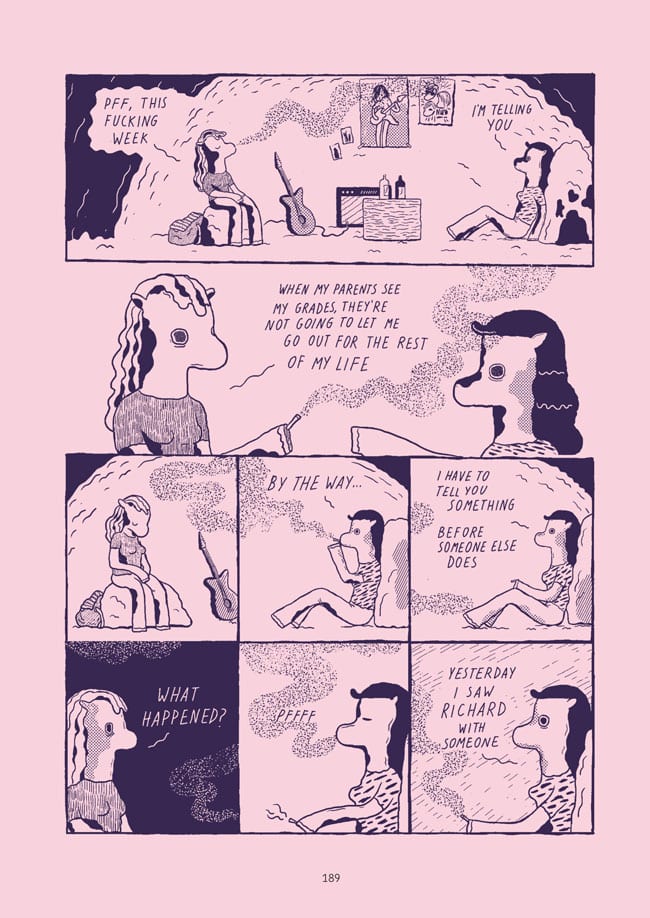

Two other standout entries are “Arrabiata” by Sergi Puyol and “Horse Meat” by Ana Galvañ. Puyol’s faux naive drawings remind me of Lille Carré’s, but Puyol demonstrates a much sparer narrative approach in this pleasingly ambiguous tale of a troubled man who never speaks, much to the consternation of his wife. Ana Galvañ’s story is a sort of existential satire of My Little Pony, featuring teen girl ponies navigating boys, girls, their relationships to one another, as well as drugs and subsequently, alternate realities. It’s a weird, whimsical brew that works. The former is printed in a three-color scheme on yellow paper and the latter features dark blue ink on pink paper; lending each of them the appealing look/feel of high-end risographed minicomics.

Another especially notable piece is “Let’s Move to the Country! You Said to Me” by Clara-Tanit Arqué, in which a young mother goes through her exhausting day caring for home and hearth, her young child, and her bed-ridden mother. The whimsy of Arque’s wonderful drawings is ironically counterbalanced by her protagonist’s underlying sense of desperation.

The book has some shortcomings. Though the quality of art and writing remains generally solid throughout, with no outright stinkers and several excellent stories, Spanish Fever would have benefited from a couple of what critic Rob Clough calls “tentpole pieces”–generally longer, major works around which the rest of the collection is shaped (Kolor Klimax boasted stories such as Johan F. Krarup’s heartbreaking “Nostalgia”, which added some real gravitas to the collection). Most of the stories in Spanish Fever are quite brief and even some of the longer stories are mere trifles (however professionally rendered), giving the book a piecemeal feel (perhaps inevitable in a collection with more of a comprehensive rather than curatorial mission). And if Spanish Fever is meant to showcase the country’s diversity of independent comics creators, rather than having a specific theme, it falls particularly short in one area: with 28 contributors, the fact that only three are women is glaring. That each of these three female-created comics are excellent only accentuates this imbalance. Some outright LGBTQ representation would have been nice as well. For example, Nazario, who is based in Barcelona, has some beautiful work featured in Justin Hall’s No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics (Fantagraphics, 2012), and the artist’s bio in the book notes that he is “generally considered the godfather of Underground Comix.”

Despite these few misgivings, I find Spanish Fever an overall laudable effort to introduce North American readers to another world of comics creators from across the ocean. Given the current, alarming increase in xenophobia, isolation and bigotry here in the USA (and globally), here’s hoping that Fantagraphics continues publishing comics collections such as this–from Spain and other countries–that promote and celebrate comics as a shared, international language.