Editor and artist Tom Humberstone has made each new volume of his anthology Solipsistic Pop ever more complex, beautiful, and formally interesting. It is a formalist's funhouse in the vein of a Chris Ware, Jordan Crane, or Richard McGuire. To be sure, there's plenty of narrative and emotional content to be found here as well (as there also is in the work of Ware, Crane, and McGuire, of course), but the artists in this anthology run with this issue's theme ("Maps") and take it all the way. Funded by an Indiegogo campaign, Humberstone spared no expense in making the whole package look just right.

I say "package" quite literally, because there are any number of intricate parts that make up this anthology. SP4 comes in a blue folder with comics on the front, back, and inside, depicting the prologue, key, and epilogue to John Miers' story, "It Is Always Too Late To Save Krypton". This story primarily uses symbols to depict its dialogue (except in one sequence designed to mimic a Golden Age comic) that tells the story of Superman (here called The Visitor) as a sort of recursive loop where no planet is ever saved. Inside the folder's flap are three postcards designed to be taken outside and on trips: a game of "Walking Bingo" by Oliver East (in which we look for things like "a wolf tree," "a massage parlor in an industrial estate," and "a gate or fence that looks like a painting"), a glow-in-the-dark comic by Takayo Akiyama, and a card by Jenny Robins that's designed to be planted (her statement in the comic that "ideas take root" is a tad on the nose). The book's dust jacket is one huge drawing by Katie Green called "Maelstrom I", a series of swirling patterns of small, repeating objects emanating from her drawing hand in the center of the page, with the admonition to "draw every day." The strip is recapitulated in the final page of the book, as the reader is drawn back and we see the artist at work, her Bristol board serving as a map of all that she sees.

All of this is before we even crack the book. The cover, by Stephen Collins, is itself a clever strip that uses a subway map's stops as a series of individual thoughts by different riders, with the Red and Blue lines sizing each other up and finding the other pathetic, among many other funny observations. Collins's wit is also on display in the first story of the book, "The A to Z of Mrs. P", which is about Phyllis Pearsall, the creator of London A to Z, a famous London mapmaking company. Done in a 6x8-panel grid, Collins silently takes us through her life's difficulties by way of a guiding green line that is occasionally interrupted by times of tragedy and injury until she found her calling. This opening story introduces the reader to the way the book will unfold: there's a single spot color used (a greenish-yellow) and every story will hew fairly closely to the book's theme.

Given that comics and maps already have a bit in common (image and text mixed to transmit information and give the reader a guide to a territory), it's no surprise that this theme seems to suit its artists snugly. The strongest stories in the book are those where the artists are able to use geographic tropes as part of a narrative. The weakest stories are those that touch vaguely on the subject as a jumping-off point. As an example of the latter, Marc Ellerby's "Belgish", Joe List's ""Bovis the Rabid Island", and Ste Hitchens's "Gulls" only connect to the theme in the loosest of senses. Though these stories are nicely drawn, they fade quickly from memory.

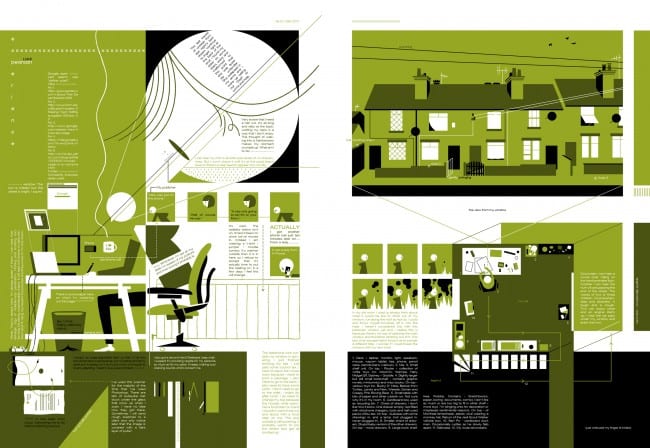

Luke Pearson's "Experience" is my favorite strip in the book. This is a map both of his house as well as his emotions, drawn diagramatically à la Ware. There are a number of great tiny-lettered jokes, including one where his partner makes fun of him for the small number of phone calls that he gets. Pearson also gets great use out of the spot coloring in terms of design, all angles and triangles. Edward Ross's "Maps To Live By" is the most emotional piece in the book, as Ross traces back his lineage to his great-grandparents, one Scottish and one Indian. Their son Andy was sent to Scotland when he turned 18 after a lifetime of being made to feel like he doesn't belong. His most important possession, "one of the few things [his father] ever gives him," is a ticket and a map to people who can help him. Andy's son (Ross's father) also feels adrift and without a real identity, despite having a family. What's wonderful about this story is the metaphor of life as map, where one can only start to understand oneself through one's children, because "at least you can show them where you got lost." The way Ross jumps back and forth in time winds up creating an emotional narrative that links up the fractured chronology, and the way he flips between using smaller and larger panels to emphasize events and faces is equally clever.

A couple of artists used actual maps as background art to ground their narrative. Joe Decie's "Always/Never" is an emotional and chronological account of his super-ego. Streets and buildings on a map are marked in territories called "Always" ("Tell The Truth", "Wash Your Hands") and "Never" ("Throw stones", "Bite"); these evolve from page to page as the boy depicted ages. The punchline is what the boy says: "Sorry mummy" as a young boy, "Sor-ree didn't mean to" as a pre-teen, "Sorry! Jeez can you stop going on about it" as a teen (with anxieties mounting), and "Listen, I really regret the circumstances...blown out of proportion...agree to disagree?" as an adult, with "Say you're sorry" a very distinct entry in the "Never" column. The way that the specifics are organized on the page is quite clever, down to the letters and number keys running around the page. In "You Are Here", Tom Humberstone and Matthew Sheret provide a key to a group of tightly packed spots on a street, where each number takes us up the street but also tells a fractured narrative of negotiating the streets during a riot. It's both harrowing and intimate in equal measures.

There are a couple of stand-out stories that refer back to mapping emotional spaces. Alison Sampson's "Small World" is a home map not unlike Pearson's, but this story is told while she is in the process of losing her job and describes what the things in her flat mean to her: "form follow function" describes a workspace, "an escape and a pleasure" describes a hanging toy, etc. It's a way of recalibrating and comforting herself until she's ready to go out and find a new job. Anna Saunders's "Roots" is less a map than a topographical equivalence between roots and the hands of her mother, showing how her mother's influence turns her from child into adult (and sapling into tree).

At a tight eighty pages, with no story more than four pages, Solipsistic Pop 4 doesn't wear out its welcome. Even the lesser stories still serve as pleasant confections, even if they lack the impact of the better stories. It reminds me a bit of Jordan Crane's old anthology Non in its combination of handmade/DIY flourishes mixed in with the skill of a master designer who takes great pains to create an aesthetic gestalt that goes beyond simple theme. Humberstone's commitment to showcasing a variety of styles, from cool clear-line works to more primitivist and expressive comics, shows that he's serious about providing a format that manages to flatter and feature both ends of the comics aesthetic scale. In turn, the stable of artists that contribute take this opportunity seriously and never turn out less than their best work. Tom Humberstone's commitment to innovation and the confluence of form and content to create something beautiful and moving makes this annual anthology a treasure for the entire comics world.

At a tight eighty pages, with no story more than four pages, Solipsistic Pop 4 doesn't wear out its welcome. Even the lesser stories still serve as pleasant confections, even if they lack the impact of the better stories. It reminds me a bit of Jordan Crane's old anthology Non in its combination of handmade/DIY flourishes mixed in with the skill of a master designer who takes great pains to create an aesthetic gestalt that goes beyond simple theme. Humberstone's commitment to showcasing a variety of styles, from cool clear-line works to more primitivist and expressive comics, shows that he's serious about providing a format that manages to flatter and feature both ends of the comics aesthetic scale. In turn, the stable of artists that contribute take this opportunity seriously and never turn out less than their best work. Tom Humberstone's commitment to innovation and the confluence of form and content to create something beautiful and moving makes this annual anthology a treasure for the entire comics world.