I read Kat Leyh’s Snapdragon for the first time several months ago with zero context, when it arrived in a box of advance reader’s copies. It wowed the hell out of me. I pitched my editor. I set it aside. In the meantime, my feelings about it faded and dulled. Could this little YA book really be as good as I remembered it being? Welp, I read it again and the answer is yes. Leyh, best known for her work on Lumberjanes, has a real ability to perform a kind of open-heart surgery on her readers. With a few deft gestures, she cracks your ribcage right open, revealing the gooshy stuff inside, and massages and squeezes it all, producing intense emotions and, in the end, a feeling that you’ve been cleaned out, for the better. Snapdragon is a great example of those skills.

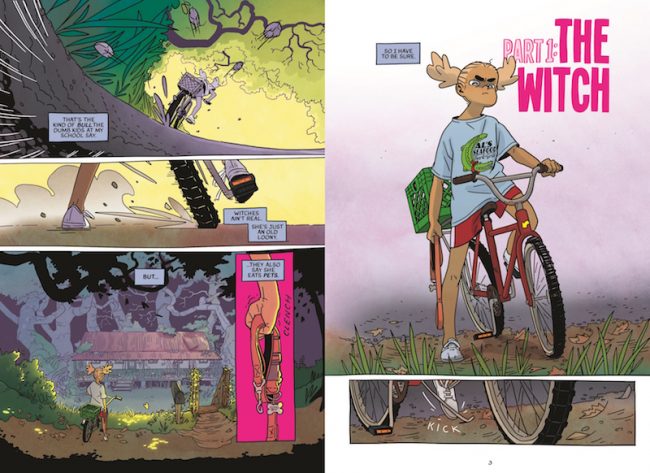

Snapdragon herself, who goes by Snap, is a black tween who likes to gather her hair up in two long bunches that resemble antlers as much as the trumpet-like shapes of the flower she’s named after. She lives with her mom (Jessamine) and her dog (Good Boy) in a trailer, and pretty much takes care of herself. It’s not that her mom is absent--she’s very present when she’s around, but she’s working and going to school, and she needs Snap to pull her weight. Jess’s ex-boyfriend is no longer in the picture, but he clearly brought trouble. Snap is a tomboy and a loner. She doesn’t like most people, just animals, and she behaves like an angry, frightened animal herself plenty of the time. Searching for Good Boy, she bravely wanders into the home of the town witch, who’s rumored to eat roadkill and cast spells with their bones, only to find a tough old woman named Jacks, whose hard exterior contrasts with her soft interior (something Leyh shows when Jacks takes off the wide-brimmed black hat and long black robe she wears outside to reveal Crocs, flowered Bermuda shorts and a t-shirt of a cat in a cowboy hat saying “Meowdy!”). All this might seem spoilery, but it’s within the first 20 pages of the book, and much is to follow.

Jacks turns out to make her living from cleaning up roadkill and putting the animals’ skeletons back together to sell online. She also teaches Snap how to take care of a heap of orphaned baby possums. Another thing Leyh does really well is to suggest something (this person is a witch), then deny it (nah, she’s just a weird old lady), then slowly circle back around to the original theory but with a new feeling behind it (um, maybe she’s a witch after all, but we need a better understanding of what witches are). It’s a technique she uses over and over again. For example, we assume that Snap has trauma because she’s poor and in a single-parent household and she clearly has a lot of anger inside. Then we think, no, she doesn’t; it’s okay for a kid to just be weird and rageful, and maybe we shouldn’t have assumed that she did to begin with. Only then, maybe she does after all. She can be strong and yet still processing pain, and perhaps we need to revisit our thoughts about what trauma looks like. I haven’t even mentioned Lulu, who starts out as Louis and slowly, bravely steps into her true self. Part of what makes the book so worth reading is that everything in it feels hard and scary and painful, but in a way that’s inspiring because the characters manage to stand up to the hard things. They don’t get everything right, and you worry that the world will beat them up in the years to come, but it’s a book about being brave more than anything else, and you can’t be brave unless you’re frightened first. Leyh lays out the stakes, and as a result the feelings she elicits are earned, not cheaply conjured.

Jacks turns out to make her living from cleaning up roadkill and putting the animals’ skeletons back together to sell online. She also teaches Snap how to take care of a heap of orphaned baby possums. Another thing Leyh does really well is to suggest something (this person is a witch), then deny it (nah, she’s just a weird old lady), then slowly circle back around to the original theory but with a new feeling behind it (um, maybe she’s a witch after all, but we need a better understanding of what witches are). It’s a technique she uses over and over again. For example, we assume that Snap has trauma because she’s poor and in a single-parent household and she clearly has a lot of anger inside. Then we think, no, she doesn’t; it’s okay for a kid to just be weird and rageful, and maybe we shouldn’t have assumed that she did to begin with. Only then, maybe she does after all. She can be strong and yet still processing pain, and perhaps we need to revisit our thoughts about what trauma looks like. I haven’t even mentioned Lulu, who starts out as Louis and slowly, bravely steps into her true self. Part of what makes the book so worth reading is that everything in it feels hard and scary and painful, but in a way that’s inspiring because the characters manage to stand up to the hard things. They don’t get everything right, and you worry that the world will beat them up in the years to come, but it’s a book about being brave more than anything else, and you can’t be brave unless you’re frightened first. Leyh lays out the stakes, and as a result the feelings she elicits are earned, not cheaply conjured.

I haven’t even mentioned the art. Leyh’s pages, considered from a distance, shouldn’t really work. She breaks panels constantly, colors (note: I assume she’s her own colorist, as I can’t find one credited in the book) in several palettes within a spread, uses word balloons to serve as panel dividers and generally just throws everything she can at us. By all rights, it should be an ungodly mess, but it turns out to be a divine one. We wouldn’t feel things the same way if we weren’t being hurried along in a mine car down twisty tracks in the dark. Snap’s expressive face (including fuzzy caterpillar-like eyebrows) would do some of the work in showing us how her emotions swing from wild delight to choleric disappointment. Ditto her tightly wound small body, which crouches and exuberates and slouches all over the place. But they don’t do everything. The star of the book is the way Leyh draws her flippin’ heart out to make a story that really doesn’t need words at all. We’d get 90 percent of it from the pictures and the way her people look at each other. And not just the plot. We’d understand how they relate to one another, the kinds of love they feel for one another, and the fundamentally generous impulse that cushions all the hard things the book contains. If we just allow the people we know to be who they are and give them space and understanding, we might just make a better world, it says.

I haven’t even mentioned the art. Leyh’s pages, considered from a distance, shouldn’t really work. She breaks panels constantly, colors (note: I assume she’s her own colorist, as I can’t find one credited in the book) in several palettes within a spread, uses word balloons to serve as panel dividers and generally just throws everything she can at us. By all rights, it should be an ungodly mess, but it turns out to be a divine one. We wouldn’t feel things the same way if we weren’t being hurried along in a mine car down twisty tracks in the dark. Snap’s expressive face (including fuzzy caterpillar-like eyebrows) would do some of the work in showing us how her emotions swing from wild delight to choleric disappointment. Ditto her tightly wound small body, which crouches and exuberates and slouches all over the place. But they don’t do everything. The star of the book is the way Leyh draws her flippin’ heart out to make a story that really doesn’t need words at all. We’d get 90 percent of it from the pictures and the way her people look at each other. And not just the plot. We’d understand how they relate to one another, the kinds of love they feel for one another, and the fundamentally generous impulse that cushions all the hard things the book contains. If we just allow the people we know to be who they are and give them space and understanding, we might just make a better world, it says.