In the first volume of Mardou's slice-of-life Sky In Stereo, teenager Iris struggles with her step-father, her mother's new religiosity, various boys at work, and most of all, her future. When she decides to drop acid by herself, that's the start of an extended sequence that starts off beautifully for her but eventually turns nightmarish when she can't get to sleep for three days, misses work, and then runs off. At the end of that volume, her fling/self-imagined savior Glen has called the police after her obvious breakdown, and Iris is forced to go to the station with her mother.

The second and final volume is about Iris' time spent in a mental institution following her post-psychedelic breakdown. Mardou has a way of recording the tiniest of meaningful details that contribute to the powerful sense of verisimilitude present in her work. While psychedelic experiences are personal and different for each individual, Mardou nonetheless got across the thought process of tripping with greater accuracy than any account I've ever read. It's a way of removing the sensory filters that we maintain for survival reasons, which can make it difficult for someone on acid to process consensus reality. Through Iris' soliloquy during her trip, the reader is taken into her understanding of the world and experiences it slowly falling apart in fits of confusion and spiraling paranoia.

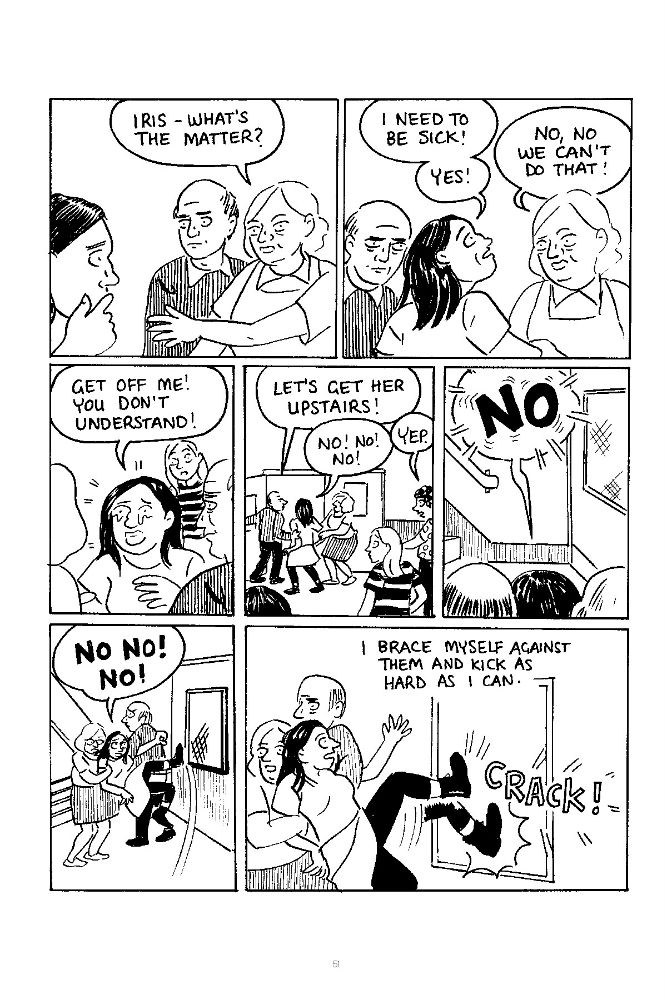

Similarly, Mardou captures the sheer, oppressive dreariness of institutional living. At the same time, Iris is utterly gripped by paranoia and conspiracy theories, imagining that the people in the hospital were supposed to be doubles of people she knew, even wearing some of their clothing. From the very beginning of the book, Mardou's delicate figure-work tells a large part of the story through subtle facial expressions and body language. Despair, hope, anger, and ennui are particularly accented in Mardou's work regarding drawing faces, and eyes in particular. When she doesn't comply with taking her medication, there is the horrible sensation of being held down against her will and drugged into unconsciousness. Mardou skillfully accents both the horror of being kept against one's will and the clear need she has for treatment.

Much of the rest of the book is Iris' slow journey into accepting institutional living, befriending fellow patients, and slowly healing from her experience as she started taking her medicine. There are no short cuts and no easy ways to obtain wisdom or get better. Time, effort, therapy, and medication slowly put her in a place where she is willing to get better. The daily drudgery and routine help stabilize Iris, even if paranoid thoughts about the devil still pop up. Mardou also gets across another essential truth about being institutionalized: one's fellow inmates can become an incredibly important part of your life. For Iris, it was meeting Miki, another young woman who also had a horrible reaction to LSD, that brought her out of her shell. The ability to relate and connect to others is a crucial part of mental health, and while those relationships are often inadvertent ones on behalf of the institution, it doesn't make them any less important or meaningful.

Much of the rest of the book is Iris' slow journey into accepting institutional living, befriending fellow patients, and slowly healing from her experience as she started taking her medicine. There are no short cuts and no easy ways to obtain wisdom or get better. Time, effort, therapy, and medication slowly put her in a place where she is willing to get better. The daily drudgery and routine help stabilize Iris, even if paranoid thoughts about the devil still pop up. Mardou also gets across another essential truth about being institutionalized: one's fellow inmates can become an incredibly important part of your life. For Iris, it was meeting Miki, another young woman who also had a horrible reaction to LSD, that brought her out of her shell. The ability to relate and connect to others is a crucial part of mental health, and while those relationships are often inadvertent ones on behalf of the institution, it doesn't make them any less important or meaningful.

Iris' recovery is not linear. An incident where she eats chicken and then regrets it leads to her being locked up in the equivalent of solitary, and she further declines to take her medications in a fit of defiance. Her struggles are often not her fault or delusional, as one doctor badly misdiagnoses her and gives her too much Haldol, which leads to a physical breakdown. At the same time, when she's on her new medication and starting to feel better, she viscerally starts to miss the "blue mind" she had when she was on acid. As a result, she stops taking her medication in order to go back to that mental space, but the joyful reunion is short-lived when her thoughts turn to images of rot and decay. Even when Iris reluctantly starts to take her meds again, she still sees a number of events in the hospital as being part of a conspiracy, as part of someone else's game.

Iris' recovery is not linear. An incident where she eats chicken and then regrets it leads to her being locked up in the equivalent of solitary, and she further declines to take her medications in a fit of defiance. Her struggles are often not her fault or delusional, as one doctor badly misdiagnoses her and gives her too much Haldol, which leads to a physical breakdown. At the same time, when she's on her new medication and starting to feel better, she viscerally starts to miss the "blue mind" she had when she was on acid. As a result, she stops taking her medication in order to go back to that mental space, but the joyful reunion is short-lived when her thoughts turn to images of rot and decay. Even when Iris reluctantly starts to take her meds again, she still sees a number of events in the hospital as being part of a conspiracy, as part of someone else's game.

Mardou nails the transition Iris feels in seeing events unfolding around her as part of a game and understanding how to play a different kind of game in order to get out. Iris pretends to be a nurse, as she's extra helpful around the ward and even cleans up after a fellow patient when she wets herself. Playing the game to seem "normal" is a common move, but it also points out that the mere ability to "fool" others reflects a level of recovery that is hard to fake. Recovery is not a precise process. It requires a willingness on the part of the patient to change their behavior and mental states, but it also requires a certain fluidity on the part of the medical providers to change tactics while treating their patients with dignity and respect. Actions affect moods just as much as moods affect actions, so Iris building bonds with others and becoming helpful had an impact on her as sure as her medications did.

Mardou nails the transition Iris feels in seeing events unfolding around her as part of a game and understanding how to play a different kind of game in order to get out. Iris pretends to be a nurse, as she's extra helpful around the ward and even cleans up after a fellow patient when she wets herself. Playing the game to seem "normal" is a common move, but it also points out that the mere ability to "fool" others reflects a level of recovery that is hard to fake. Recovery is not a precise process. It requires a willingness on the part of the patient to change their behavior and mental states, but it also requires a certain fluidity on the part of the medical providers to change tactics while treating their patients with dignity and respect. Actions affect moods just as much as moods affect actions, so Iris building bonds with others and becoming helpful had an impact on her as sure as her medications did.

Mental illness is complicated and its causes can be hard to pin down. Brain chemistry, trauma, stress, genetics, negative drug interactions, and many more factors can play into someone having a breakdown, especially during the teen years. Mardou made it clear that for Iris, a feeling of having no future with her stepfather there and her mother drifting apart from her led to her drifting away from mental stability. There's a key scene at the end of the book where Iris has a day out of the hospital with her mom, who reveals that she's split with her husband and wants to move into a smaller place with her daughter. When Iris is happy to hear the news (but equally happy to be eating non-hospital food and in general happy to be out in the world again), there's a look of subtly-depicted joy on her mother's face. It's the face of someone who feels intense relief that something she thought lost forever (her relationship with her daughter--not to mention her daughter as a functioning person) was granted to her once again. It's one of many subtle moves makes as a storyteller as she refuses to pronounce judgment on her characters; instead, she opts to emphasize the choices her characters make, both positive and negative, as they lead to eventual self-actualization.