I have to admit that the reason this book initially intrigued me is most likely a coincidence. Last year, the record label Light In The Attic reissued Sachiko Kanenobu’s Misora (“Beautiful Sky”), an album of Japanese folk music from 1972. In the sense of a singer-songwriter performing their own material on acoustic instruments, rather than traditional songs, Kanenobu was apparently the first woman to do this in Japan, making her a trailblazer of sorts. The Sky Is Blue With A Single Cloud has a title similar enough to highlight the parallels in the provenance of its contents. Kuniko Tsurita’s manga began appearing in Garo magazine in the late sixties, when she was eighteen, making her similarly a pioneer for being the first woman making experimental manga, disinterested in the commercial potential that might await one making work explicitly targeting an audience of young girls.

I have no way of knowing if either of these women would’ve been aware of or interested in the work the other was doing; characters in Tsurita’s manga listen to American jazz drummer Max Roach. It is simply a byproduct of a current American vogue for archival work from certain places, time periods, and feminine or feminist viewpoints that led to them entering the marketplace and my consciousness in such proximity to one another. For all the interest the broad strokes of her biography can generate as a marketing hook to a North American audience, considering the peculiarities of Tsurita’s stories finds them strange and compelling. Coincidentally, they’re also also abstract enough they often move more like music in how they develop and digress, rather than seeming to follow a plot and a three-act structure. Compiled here, they play off each other like songs an an album, or suites in a symphony.

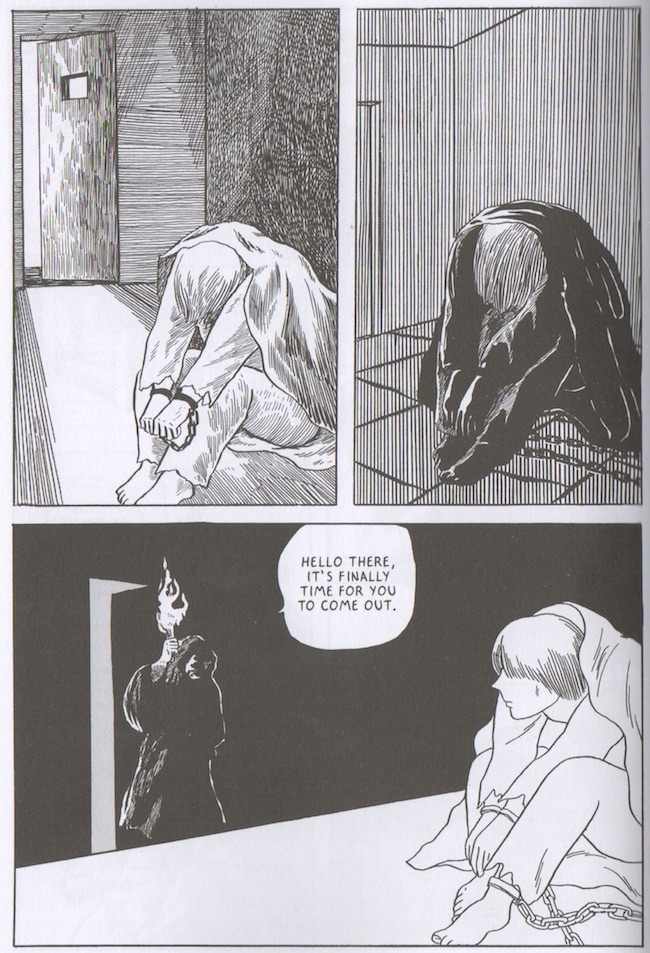

It begins with a piece that’s relatively accessible. Its story, of someone who goes around killing bad people, and is then sentenced to hell himself, and then proceeds to kill the souls in hell, only to be returned to the Earth again, is basically dumb enough to be Spawn. It’s also the work of a literal teenager, and shot through with inventiveness in its visual storytelling and paneling. One great page, depicting a prisoner being walked away from the jail to the gallows, increases the number of bars visible in the foreground as the figures move further away, precedes another great one, where the silhouette is distorted in two different ways, in an abstracted depiction of a soul’s descent into hell. The pageturn between them increases the impact of both the slow measured march towards the inevitable of the first and the new sensation of impossible pain of the second.

It’s an uncomplicated fable about wrongheaded delusions constituting an existential trap that makes one’s fate, and this self-awareness elevates it above the power fantasies of vengeance built around confusing metaphysics it resembles. When this story ends, readers are instructed to go back to the beginning and reread until we understand it, but the meaning is easy enough to grasp that such instruction feels a little condescending. Still, it’s the earliest piece included in the book, and some uncertainty on the author’s part can be excused. (It’s also titled “Nonsense,” which might be a form of self-deprecation.) Later pieces are free from such authorial intrusion, but benefit from immediate rereading to reveal the amount of forethought and construction underpinning their more oblique shapes.

“R,” from 1981, feels similarly cyclical in its construction, with the narrating voice in its first panel taking a retrospective tone regarding the story’s conclusion. The story chronicles the growth of a child, and while initially the child’s appearance is drawn with a Tezuka-like cuteness, much as a child in “Nonsense” also appeared, their growth into adulthood is depicted with a style closer to Guido Crepax, a microcosm for the development in Tsurita’s style more generally. It doesn’t actually feel like Crepax, partly due to the subject matter never approaching the pornographic, and partly because in Tsurita’s hands the inexpressiveness of her lines feels deliberate and not undercutting. Though the level of ornamental detail feels European, Tsurita’s approach to drawing faces feels closer to the masks of Kabuki theater than celebrity models, and the rest of her drawing follows an approach that favors a neutral distance that allows the reader to consider what is being conveyed without feeling the author’s trying to seduce them.

If comics are a combination of literature and visual art, which I think we can all agree they are, the literary effect of Tsurita’s more mature work is served by being able to take in the whole story as viewed as a single composition. First and last pages feel more like focal points to consider than the beginnings and endings of a story which a reader’s imagination can then extend in either direction. The story “Max,” for instance, rhymes these pages by having a very similar composition- two shots of the title character sitting in a chair, the front and from behind, and a close-up of her mouth smoking a cigarette. Reading “Max,” a sense emerges, present also in a story called “Calamity,” that the end of the story - all our stories - is death, and while we can perhaps look back to review our lives and have regrets, the fact of death as an inevitability was always going to be a foregone conclusion. “Calamity” is a story, like “Nonsense,” where a character is condemned to death despite their viewing themselves as innocent; unlike “Nonsense,” we don’t see the protagonist committing crimes, only being introduced after they’re imprisoned.

Death hangs over so much of the work here, but the circularity of so many of these stories means they bypass the classical form of tragedy entirely. One story is called “The Tragedy Of Princess Rokunomiya” but, if I’m reading it correctly, climaxes at a moment of ambiguity as to how the story should even be read. The title character performs anti-social behavior and gets hit on by cool dudes who come on to her by saying she seems enlightened. She says there is only one thing she sees or thinks about, and then, on the last page, when left alone, breaks down weeping, lamenting her narrow eyes. It’s unclear if the “tragedy” of the title is sincere — narrow eyes in the sense of a narrowness of vision, a preoccupation with death that cannot be overcome to feel joy or take responsibility for one’s life choices — or ironically mocking the protagonist as a brat whose preoccupation with her own appearance has made her a miserable person.

Even the book’s title, once the book is read, speaks to both the sense of what is alluring about the beauty of its contents - “The sky is blue” - and the shadow of death over everything. In the story the book takes its name from the cloud in question is a mushroom cloud, but this isn’t so much an allusion to the threat of nuclear war but rather a reminder that, as far as single clouds go, the reality of looming death is a pretty large one! Obviously a single cloud does not mar the beauty of the sky as much as it marks the existence of an atmosphere. Analogously, life without death would be both impossible and meaningless.

There’s so much life and so much to love in Tsuritisa’s panel-to-panel transitions, where an engraving-indebted approach to black and white drawing renders light shifting from one moment to another, investing slightly shifts in perspective with gravity, while other panels depict the act of flipping a fried egg with both perfect grace and the implicit humor of a non sequitur. These tones existing alongside one another accrue an unforced beauty. Despite the association with realism, for a stylist like Tsurita, there’s no real distinction between detail and the decorative flourish. Any intensity is rendered exquisite. And yet it still feels loose, cartooned, moving from one panel to the next as naturally as you exhale after an inhale.

The tragedy of Kuniko Tsurita is that she died young, at 37, after a protracted battle with lupus. All the work collected here possesses a youthful vitality, and bears the mark of her transmuting her time and her experiences into literature. Translator and historian Ryan Holmberg and editor Mitsuhiro Asakawa write an essay discussing the contents of Tsurita’s library, the authors she read that would’ve influenced her, like Robbe-Grillet and Beckett. Reading her manga, her work recalls other women who would’ve been writing at the same time, who Tsurita might not have been aware of, due to their not having been translated into Japanese. There are tonal similarities to works of Ann Quin and Clarice Lispector, a quasi-autobiographical chronicle of being hospitalized contained here has enough dreamlike touches to feel reminiscent of the stories of Anna Kavan.

By my estimation, Tsurita was making fully mature work by the age of 22, with a story called “Sounds.” That piece feels provocative, not in the sense of transgression, but as a thought experiment. It’s about a person who wakes up invisible. They are never seen as they make their way around an apartment, disembodied. Unable to manipulate the objects around them in the manner of an H.G. Wells Invisible Man, their voice is the only indication of their existence. They argue with material person, sleeping in what was once their bed, and despite the underlying existential issue their being alone would present, in the interactions between them, there is humor: “I see that you have never read A Common Sense Guide To Not Embarrassing Yourself. How embarrassing,” the invisible figure says to a person with a body who is still able to eat food and choke enough to cough.

The last story in the book was actually published in a mainstream magazine, (e.g., one with a heavier editorial hand) and feels a little more polished than what has come before, but it still shares the preoccupation with death, and the sense of existing in a closed loop. Two people fall in love, the man disappears, seemingly dead, but the conclusion finds the woman convinced he traveled back in time to ancient Egypt, and that the plane he flew in has been preserved into the present as a hieroglyph for her to encounter. This could be the beginning of a larger tale, but a sequel was never executed, so all there is to do at the end of this time travel story is to return to the beginning, either of the story or the collection.

There’s a bunch of stories I like here, as well as some earlier attempts at abstraction where whatever is being reached for is not being communicated to me. Taken as a whole, it feels like there is nothing the book lacks or doesn’t contain. Another story from early in Tsurita’s career, “Anti,” is similar to “Nonsense” for seeming kind of obvious on initial reading but feels differently when considered alongside her larger body of work. It’s about a filmmaker who accidentally captures someone’s real death on film, but his friends view it as faked, an effect achieved for the sake of cinema. It’s easy to read this sort of thing and feel like you’ve seen it before, but here it’s being presented in a formally interesting way, where the filmic sequence runs ints panels in vertical columns to indicate a film strip, but interjections of larger panels show the viewers’ disengaged reactions. When read generously, knowing this is the work of an intelligent young woman whose work is grasping for something that might be beyond her ability to articulate at this point in her career, it can be seen as being about how the reality of death cannot be truly “captured,” on film or otherwise, because the nature of how an onlooker processes it will by necessity be dismissive of the reality of death when experienced subjectively. The filmmaker, the artist, knows enough of the facts to come closer to the truth. Every subsequent story is another reincarnation, that when laid end to end constitute an unclouded vision.