Sex is an ongoing Image series written by Joe Casey and illustrated by Piotr Kowalski that examines the aftermath of the midlife crisis and subsequent retirement of a Batman-esque vigilante called The Armored Knight and the resulting effects on a supporting cast of thinly-veiled analogues whose resemblance to their Time Warner-owned source characters is as obvious as can be without inciting litigation. As the title suggests, there is a special focus on their sex lives. All the gang is here: repressed millionaire Cooke, still reeling from death of Alfred stand-in Quinn; his young ex-sidekick Keenan Wade; his on-again-off-again rival, the catty woman Annabelle Lagravenese; jokester the Prank Addict; and a deformed Penguin-esque kingpin known as The Old Man. By focusing in on the already-there lurid undertones of these blatant stand-ins, Casey and Kowalski position Sex as a commentary on the state of the mainstream comics industry, its readers, and its most prevalent genre. Exactly what they have to say however, if they have anything to say at all, is impossible to tell. Sex’s content is as gratuitously and dumbly provocative as its title—but damned if I don’t mean this in the pejorative sense. It’s the weirdest manifestation of a writer’s midcareer crisis that the comics medium has seen for some time, an M-for-Mature masks-and-capes porno with a predilection for existential monologues, grandiose posturing, and strikingly candid self-reflection.

*

I don't want to compare Sex directly with the work of Steve Gerber, but reading these first two collected volumes got me thinking about the 1970s problem child of the Marvel Bullpen. Probably best known for his mid-seventies runs on The Defenders and Howard the Duck, Gerber is revered as a progenitor of a particular mode of comics storytelling, often characterized through oversimplified terms like “meta” or “self-referential,” and overshadowed by the writers he influenced who followed him. A more precise descriptor of the Gerberian mode would be self-critical; he was interested in exploring the often negative implications of the audience’s demand for the same old genre tropes. Across many titles, Gerber wielded a mixture of parody, heavy-handed social commentary, and affection for Silver Age goofiness in order to betray and undermine the gratuitous and formulaic nature of violence-as-entertainment; to wit, in the infamous “Zen and the Art of Comic Book Writing” issue of Howard the Duck, an illustrated essay detailing the author’s imagined nervous breakdown, Gerber lampoons the “obligatory comic book fight scene” by offering a perfunctory dada skirmish between “an ostrich and a Las Vegas chorus girl against the mind-numbing menace of a killer lampshade in a duel to the death,” while an earlier issue straightfacedly condemns the Kung Fu pop fad—epitomized by films like The Street Fighter and Doug Moench’s then-popular Master of Kung Fu comic—for its damaging influence on youth. Similarly, much of Gerber’s Defenders run concerns itself with its heroes’ inability to make a difference when faced with real-world enemies like institutional racism, poverty, and religious extremism.

In the 1980s, of course, Alan Moore took Gerber’s ball and ran with it in a string of, for better and worse, now-touchstone deconstructions including Miracleman, Watchmen, and The Killing Joke. More recently, Grant Morrison has cemented a vibrant and profitable career championing an optimistic, reconstructed view of the transformative and allegedly reader-empowering qualities of corporate-owned intellectual properties, eschewing Gerber’s influential cynicism.

Despite the datedness of much of his satire, what continues to make Gerber’s work so interesting (and frustrating to some) is the meta-story of the writer’s relationship with his work. Neurosis-stricken writers questioning, Plato-like, the value of fiction itself abound in Gerber’s writing. One could bookend his career with “Song-Cry of the Living Dead Man” from Man-Thing #12 and its posthumously published sequel The Infernal Man-Thing, two horror stories about the costs of writing-as-a-career starring Gerber stand-in Brian Lazarus. As is apparent in this 1978 Comics Journal interview, Gerber felt frustrated and hemmed in by the dictates of mainstream publishing but never quite comfortable outside of the parameters of the genres he felt increasingly ambivalent toward.

*

The above digression is meant to serve my point that Joe Casey’s Sex embodies a similarly compelling ambivalence towards its writer’s typical choice of form and genre. It aspires to be a statement on the mainstream comics industry from a writer who, like Gerber, has written too extensively for the major publishers and their well known IPs to be considered a true outsider and yet whose idiosyncratic ethos (neurotic, intellectualizing, self-flagellating) is undoubtedly at odds with assembly-line superheroics. It is also ham-fisted, self-indulgent, brazenly dirty, and not especially profound—but again, damned if it doesn’t work, anyway.

The above digression is meant to serve my point that Joe Casey’s Sex embodies a similarly compelling ambivalence towards its writer’s typical choice of form and genre. It aspires to be a statement on the mainstream comics industry from a writer who, like Gerber, has written too extensively for the major publishers and their well known IPs to be considered a true outsider and yet whose idiosyncratic ethos (neurotic, intellectualizing, self-flagellating) is undoubtedly at odds with assembly-line superheroics. It is also ham-fisted, self-indulgent, brazenly dirty, and not especially profound—but again, damned if it doesn’t work, anyway.

Contemporaneous reviews of the series’ first few issues heralded it as a return to the 1980s Dark Age of Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and Brat Pack, but Sex is much more personal, obliquely autobiographical in the Gerber mold. It’s impossible not to read through the lens of the writer’s self-analysis. Protagonist Simon Cooke has spent his entire adult life playing heroes-and-villains and now in retirement, without the usual costumes and conceit to rely on, he is not sure what to do with himself. The book itself, then, seems to be reflective of Casey’s own midcareer crisis, his experiment at staying, resolutely though uncomfortably, within the confines of a familiar genre while abstaining from that genre's seemingly necessary tropes and strategies: good guy vs. bad-guy brawling; fast-paced, compressed plotting; dynamic, action-oriented visual storytelling, etc. In their absence is Sex’s titular sex.

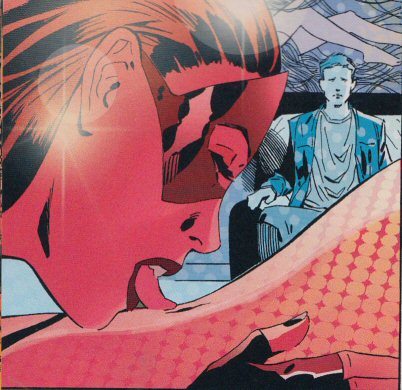

That concept is simple yet innovative. By foregrounding superheroes’ sublimated sexuality—already so obvious that it has long been the subject of Kevin Smith monologues, snarky memes, and unofficial and quasi-sanctioned works of fetish art— and replacing violence with sex as the series’ plot catalyst, Casey makes subtext mere text. It’s this lack of subtlety that drives the story, and it's what lends it novelty. The characters basically act the way we expect them to, but with the aim of getting off rather than thwarting the law or upholding justice. Cooke goes undercover to investigate the criminal activities of Annabelle Lagravenese, but only because he’s sexually curious (she runs a brothel). Instead of botched robberies, we have awkward, unsuccessful hook-ups. Instead of cinematic rooftop chases, we have pornographic depictions of an admirable variety of sex acts. Or a conflation of the two: in issue 3, Catwoman—er, Shadow Lynx—pleasures herself to memories of being tackled by Armored Knight while in her fetish-leather costume. It’s a neat trick, worthy of Gerber, whose greatest gift to above-ground comics, as he himself put it in that Journal interview, was the way his best work demonstrated the successful “departure from the standard formula of comic-book storytelling—of what can constitute a comic book, what it can do, what it can say, and what it can mean.”

But Sex is more than a simple outgrowth of Gerber’s old innovations and it is thematically distinct from the deconstructionist books many reviewers have compared it to. Despite its goofy premise, Sex steers clear of satire, Gerber’s signature approach. While I hesitate to say that a book as loud and confrontational as Sex takes itself seriously, it certainly isn’t jokey or even that clever, really, and it seems to me that that’s by design. After all, injecting sex into a standard superhero narrative doesn’t make for all that powerful a commentary when the object of satire is barely a cat’s hair removed from it; how comically outlandish can the above masturbation sequence be in comparison to the similar stuff that’s gone on in the bat-books proper, like this infamous page from the New 52’s Catwoman #1?

Instead, Casey and his collaborators are deadly, almost deludedly sincere in their desire to examine sexuality within the confines of the superhero comic. (Unlike Gerber, Casey leaves the explicit editorializing to his fascinatingly candid back matter “Dirty Talk” column. These columns aren't reprinted in the collected volumes and are only available in the original issues, which is a shame. Casey’s tirades are gloriously unhinged, offering the same cringe-inducing, voyeuristic thrill one finds in the most soul-baring autobio journal comics. Casey is also frequently insightful, and professes interest in the “fusion” comics movement conflating indie and mainstream sensibilities. Claiming his bonafides, Casey says that for Sex he “took a few standard superhero tropes and mixed them with European graphic albums, certain Milo Manara comics and more Los Bros Hernandez than you might think.”)

This begs the question: Is Sex a work of erotica? Well, compared to what passes for sexy in Big Two comics—twisty posturing and awkward anatomy painted with all the eroticism of a child bumping two plastic action figures together—Sex is downright steamy. Viewed in their own context, however, the neon-cast sex scenes aren’t terribly titillating. Kowalski's depictions are clinical and porno-stagy. It’s hard to tell if his style—distinctly European, given to more detail in backgrounds and futuristic cityscapes than in relatively plain human figures—is not adept at nuances of facial expression or if the characters are just appropriately grimacing, but the scowls and dead-eyed glares in the sex scenes strike me as a deliberate choice. Besides sex, there’s a lot of talking in this book, and Kowalski applies the same staid, talking-head quality of these dialogue-heavy scenes to the sex. For a book titled Sex, no one looks like they’re having much fun engaging in the eponymous act. Brad Simpson’s coloring contributes greatly to the seedy vibe, alternately adding a sense of gooey strip-club lighting or antiseptic airlessness to the proceedings.

Perhaps to add some dynamism to the intentional lack of fluidity, Kowalski shines brightest in his subtly playful page layouts, employing irregular panel sizes to communicate the passing of time or to emphasize awkward pauses or insets to highlight important details.

One wordless page in issue one shows Simon driving through the red light district bashfully eyeing the sex workers he passes on the street. It’s this page, I think, that epitomizes Sex. To be honest, I’m not sure what to make of it, not sure what to make of the Simon Cooke character at all. Both he and his writer Casey struggle to view Cooke as more than an archetype—for vigilantism, for justice, for genre tropes, for Batman—and as a fully developed, sexual being. It’s hard to say just what Casey wants to say about sex and the modern superhero. In “Dirty Talk”, Casey admits that he isn’t sure, either. He calls the series a “laboratory” and “remind[s] anyone who picks up this book looking for some sort of definitive statement… they’re missing the point.”

True to that, Sex is often oblique and leisurely paced. It seems high concept—an orgy of Batman analogues!—but it’s not particularly interested in this hooky concept. The book doesn’t really have much to criticize or say about the familiar archetypes it so keenly observes. It treats these outlandish superfolk like honest-to-god people even though they are as one-note and interpretable as the spandex-gods on which they are modeled. And it’s all the more interesting for Casey’s lack of a thesis. It’s kind of a train wreck, but a fairly artful one, a veteran bullpenner’s take on a heretofore underground subgenre, that slick-but-Art Brutish approach epitomized by books and zines by the likes of Ben Marra and Johnny Ryan that offer a voyeuristic look inside an id-driven, pop-culture-addled mind.

Recent controversy involving Manara has publicized the uneasy place of single-entendre eroticism in the more typically cheesecakey arena of mainstream comics. If there’s a flaw that threatens to undo Sex’s appeal as it proceeds forward on the vague, endless journey of an ongoing series, it’s this: the question Casey, Kowalski, et al., seem to be asking is What does sex have to offer the comics medium? rather than What does the comics medium have to offer sex? The distinction is that, ensconced like Gerber in the genre’s traditions, Casey takes for granted the necessity of the tropes he wants to explore and explode. Like Cooke, he is trying to move beyond the latex-mask clichés of the life he’s chosen but he isn’t quite sure what to do with himself once he has.

I don’t want this to be a condescending “guilty pleasure” sort of review. Sex is thrillingly bizarre—but is it good? Is it smart? Does it have to be smart to be good? Does it have to be saying “something,” making a “statement” to be smart? Is it the Plan 9 of mainstream comics? (No—Jim Balent’s Tarot is.) That it elicits these questions, as well as such an—I admit—reluctantly positive response from me, is a testament to its idiosyncratic charm.