The last time I read a book that won the Pulitzer Prize - or at least, the last time I read a book for the specific reason that it had won the Pulitzer Prize - was Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, in 2011. The paperback has a nice colorful cover, the kind of thing that catches your eye if you’re browsing in an airport, which I was. It’s a story about a bunch of people whose lives intersect, sometimes profoundly and sometimes only glancingly, spread over multiple decades. Each section is set in a different time frame and much of the pith of the book comes from seeing the discrepancy between how characters and situations are perceived at different removes and over long spans of time. Every review of the book I read also focused attention on a section told exclusively in PowerPoint notes, an effect intended to illuminate the mental processes of an autistic child.

It was, in any event, the last piece of contemporary fiction I read for many years, right before I entered grad school, and it served as a good flashing neon warning sign keeping me away from further excursions in contemporary fiction. It seemed to have been built from a kit, in terms of all the moves an American realist novel was supposed to make in the early years of the twenty-first century. There was the massive time frame, told in tiny chapters over a large span, meant to illustrate the sweep of history. There was the large cast of characters, none of whom were really very interesting or appealing on their own, but there were a lot of them to keep track of so that people feel like they’re getting their money’s worth. And finally there were the formalist gestures in the direction of some kind of post-post-modernist stylistic play, not perhaps the kind that requires a supplemental guidebook to decipher. The kind you could explain to undergraduates in ten minutes, with some confidence that anyone who listened would be able to regurgitate something at least vaguely coherent for the midterm.

Not that the Pulitzer Prize has ever been a hallmark guarantee of greatness in American fiction, or formal excellence or even forward-thinking. The Pulitzer, like any other award, signifies what the award committee want to honor and elevate, nothing more. Sometimes it intersects with good, occasionally even great, but like any other award the most frequently intersecting virtue remain consensus.

I could see Rusty Brown winning the Pulitzer this year. It’s that kind of book.

Rusty Brown is the product of twenty years’ work by Chris Ware. It’s also, it should be noted, only part one of the story - the book ends with a giant Intermission splash page, as ominous a threat as this critic has seen in many a moon. The present volume is about 350 pages, if Vol. 2 follows suit the complete Rusty Brown saga will add up to around 700. There will undoubtedly someday be a slipcase with both books, probably in paperback, probably in time for Christmas in 2022 or 2023. It will be a gorgeous slipcase I am certain.

Do I sound skeptical? I don’t mean to sound skeptical, after all, Rusty Brown is an excellent book. Should we get that away up front? This isn’t a hatchet job on one of of our greatest living cartoonists’ magnum opus. As fun as that might be to write, it would be dishonest, because I can’t tell you this is a bad book in any way. On the contrary, it’s definitely excellent. Critics get a bad reputation as people who like to shit on other peoples’ parades, and that’s not completely unearned - but the worse part of being a critic, worse even than the expectation of knee-jerk negativity, is the impulse to hyperbole when faced with a work of genuine and legitimate significance. It’s good. Put down the thesaurus and walk away slowly, Ms. Kakutani. We get it.

Do I sound skeptical? I don’t mean to sound skeptical, after all, Rusty Brown is an excellent book. Should we get that away up front? This isn’t a hatchet job on one of of our greatest living cartoonists’ magnum opus. As fun as that might be to write, it would be dishonest, because I can’t tell you this is a bad book in any way. On the contrary, it’s definitely excellent. Critics get a bad reputation as people who like to shit on other peoples’ parades, and that’s not completely unearned - but the worse part of being a critic, worse even than the expectation of knee-jerk negativity, is the impulse to hyperbole when faced with a work of genuine and legitimate significance. It’s good. Put down the thesaurus and walk away slowly, Ms. Kakutani. We get it.

...and that’s roughly where I left off, oh, about a week or so ago, when I first sat down to bring my thoughts into some kind of order. I had a longish trip to prepare for, which entailed a great deal of preparation, and I really didn’t want to travel with Rusty Brown peeking out of my suitcase. Amazon - our modern Terminus, god of boundaries for a culture obsessed with weights and measures - helpfully informs me that Rusty Brown (Volume One, of course) weighs 3.6 pounds. That’s a lot of book to pack, but truth be told, I failed in my first attempt at storming those fair shores. Into the suitcase went Rusty Brown, and with it my hopes of leaving Chris Ware behind as I began my vacation.

As these matters turn, however, a delay was in order. Putting the book out of my head, I busied myself with the business of travel and other personal commitments. Writing problems are the kind of problems that are best solved with time and distraction, so I felt confident that if I waited through a few days of unrelated life, An Answer to the dilemma would appear.

An Answer to the Insoluble Dilemma of Mr. Chris Ware, by the World Renowned Critic, Dilettante, and Bon Vivant Tegan O’Neil . . .

Sure enough!

Thanks here are due and duly meted to Tom Spurgeon, whose words on the matter came just in time to serve as a bucket of cold water atop my own concerns. The gist of the sentiment expressed therein can be best summed up by the first sentence of Spurgeon’s brief piece: “I find the nasty undercurrent of the pushback against Chris Ware to be pretty weird.”

I doubt Spurgeon was trying to deliver the equivalent of a cattle prod up my metaphorical ass, but it was enough to completely scatter like tenpins my own thoughts on the matter. Because, sure enough, here I was writing my own response to the book, an initial response that was itself strangled in the crib by my own inability to overcome a locus of negative associations with the object in question. Spurgeon’s words cast my own motivations in a much darker light. To wit: why had my own feelings towards the book become so tinted by animus? I still remember quite clearly the groan that escaped my pursed lips when I opened the package containing the book. I love getting free books in the mail - “getting free stuff” being the best and most honest reason to be a critic, if we’re being frank - so why did this book elicit a groan? The most anticipated book of the whole gosh dang year?

Perhaps it is as simple as this: it is very fun to point out that an Emperor has no clothes. Everyone loves doing that, and it’s one of the singular joys of the critic to be paid hard American cash to whittle titans down to manageable size. The problem here is not that this Emperor has no clothes, because this Emperor is very clearly clothed in the most impeccably tailored and elegantly designed men’s fashions. Perhaps not strictly a la mode, but of the kind of sturdy construction designed to outlast whatever seasonal fads might surround it. This Emperor is not only not naked, his clothes are obviously the product of great care and attention, a lifetime’s worth of craft.

If I had to guess, it’s the “obviously” that sticks in peoples’ craws. Perhaps I’m merely projecting? It’s a frustrating experience to write about a work that so reflects the deep and abiding mastery of its author. You can like or dislike Rusty Brown - and it might be appropriate to point it, as “good” as the book may or may not be, it’s still up to you to decide whether or not to read or to enjoy - but you can’t say Ware doesn’t know what he’s doing or that the total fails to add up to less than the sum of its parts. He most certainly knows what he’s doing, and it most certainly hangs together.

But ah, you ask, just what is he doing?

Perhaps that answer to that question reveals the wellspring for much of the animus. The reason why I decided to begin this review with a brief discussion of a ten-year-old winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction was precisely to illustrate this concept. The reason why, perhaps, Chris Ware rubs so many people the wrong way in 2019 is that his artistic goals and aesthetic prerogatives are not simply apart from the run of contemporary comics, but totally alien. He’s not even playing in the same sandbox anymore, really.

There’s a small panel of critical plaudits on the book jacket - itself, as you probably expect by now, a text of no small significance - with eight quoted recommendations from Mr. Ware’s long publication history. Four of them are compliments from contemporary writers: Dave Eggers, David Sedaris, Zadie Smith, and Rick Moody. Another compliment comes from popular film director J. J. Abrams. The remaining three are simply credited to institutions: both The New York Times and The New York Times Book Review, as well as The Guardian.

See what I mean? Chris Ware isn’t really our problem anymore. He belongs to the world, for better or for worse.

And honestly? Yeah, as a critic-in-residence for the medium’s foremost putative English language paper of record that kind of does rub me the wrong way, but I’m not going to sit here and try to pretend that my feelings in the matter actually reflect any virtues or lack thereof in the work itself.

“Mais oui,” Monsieur Poirot’s eyebrow arched in response to the sudden appearance of the crucial clue, “the green eyed monster. She comes for us all in the end, Hastings.”

The problem with Rusty Brown in 2019 is not that the book isn’t “good,” whatever the hell that means, but that it’s doing something not a lot of people in this field are going to find natural sympathy for in 2019 - this is, translating the idiom of mid-to-late century American realist fiction into the comics medium. In that respect it is as much a genre-medium transplant as the superhero stories that began to gain a real foothold in cinemas starting at the turn of the century. Almost precisely the time Jimmy Corrigan was first collected and began collecting praise, incidentally. In the later twentieth century the most prestigious literary output in America was the kind of doggerel realism practiced by, y’know, the Updikes and the Roths and the Franzens of the world. Ware fits neatly into that tradition, and you don’t need to know shit about comics to understand that.

Which perhaps explains a bit of that aforementioned ire: when Noted Comics Scholar Dave Eggers says something like, “arguably the greatest achievement of the form, ever” (a real quote, apparently) my reaction is simply to ask the bonafides by which he arrives at such a tendentious judgment. (I realize that probably means I’ll never be published in McSweeney’s, so y’know, sad trombone.) Ware flatters the literary establishment by producing, in our medium, a note-perfect adaptation of the kinds of books the contemporary literary establishment makes a regular habit of heaping with praise. Of course that’s going to appear enormously flattering to folks who care about that manner of foofaraw.

All of which is to say, it is to Ware’s great misfortune as an artist that his work found such ready success outside the medium’s traditional haunts. Because as good as he is - and he is good - the praise heaped upon his work by the literary establishment only serves to estrange him from his natural constituency. Even though he isn’t a carpetbagger, the praise is alienating and awkward from the perspective of someone still stubbornly looking at his career as a whole. He was in RAW, for the love of God. His bonafides are just bona.

Of course Ware seems comically overpraised. Jimmy Corrigan was a great book but it’s not even the best book produced by RAW alumni - the first ranks of which feature the likes of Maus, Jack Survives, and From Hell, as well as the entire corpuses of Lynda Barry and Jacques Tardi. Is Jimmy Corrigan better than all of these, or any of these? Beats the holy living fuck out of me, and I don’t even like Maus.

Also, incidentally, does not matter in the least.

Anything said on the matter of the actual contents of Rusty Brown should account for the fact that this is only the first half of the work. I gave up on following Ware’s work in periodical form over a decade ago, when it became clear not merely that 1) everything he ever touched would eventually be collected, and 2) he delights in nothing so much as creating the most fussy and persnickety packaging imaginable. I realized a while back the only time I ever thought of Ware was when I had occasion to move my library, a process which entails a disproportionate amount of time spent on the dispensation of Chris Ware’s bibliography. Acme Novelty Library #15 is perhaps the most difficult book I own, in terms of packing, and I curse the artists name whenever I have to pack it anew.

A (mild) exaggeration, perhaps, but perhaps not altogether tendentious, either. He demands a lot from the reader, in terms of their ability to follow him down whichever exquisitely designed rabbit hole he decides to scamper. Building Stories was a box with some pamphlets or something in it, I never found out and probably never will because it reminds me less of a book than a peculiarly banal RPG supplement put out by TSR - Ravenloft: The Cancer Screenings. An extraordinarily reader unfriendly package, is what I’m trying to say.

Rusty Brown, therefore, at least starts off on the right foot, in terms of it being an actual, you know, book, and not a box of loose odds & ends. But again, it’s still incomplete, and so we’re left in the position of having to judge half a story. There’s a lot of good stuff in here, but since the finished product is probably going to weigh in at around 700 pages, a great deal depends on the payoff, which has not yet arrived (at least for those of us - the bums! - who have not read the work in pieces prior to receiving the finished edition).

The book begins in the mid 1970s, introducing us to a small coterie of main characters all connected by their having attended or worked at the same middle school in Nebraska during the same period of time. The title character is the least interesting of this bunch, to be frank, a character who eventually blossoms into an exhausting manchild obsessed with superheroes and pop culture memorabilia, lost completely in a world of selfish and self-serving fantasies. (This volume doesn’t actually showcase Rusty’s adult life, but I know from the last few issues of Acme I caught that his story doesn’t get any happier from here.) Said fantasies are only appealing because his daily life is pretty awful, defined by parental neglect bordering on outright mockery, to say nothing of frequent abuse suffered at the hands of his less socially maladjusted classmates.

He’s an odd figure to build a book around, because he’s absolutely repulsive in every way - not even the gradual revelation of how badly his parents failed him builds any sympathy on the readers’ part, because his personality traits have been baked in and set from a young age. Narcissistic delusions of the kind he indulges are an obvious escape, but the warp and woof of said fantasies are venal and self-absorbed to a degree that approaches pure grotesquerie.

Rusty is the son of Woody Brown, a man on most days barely more cognizant of his surroundings than his son. He teaches English and once harbored dreams of literary achievement, which we learn in the unfolding of events amounted to little more than the cover feature in Nebulous: Worlds of Imagination.

That story, “The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars,” occupies much of the elder Brown’s section. It’s a remarkably depressing story - in all seriousness, this reviewer skimmed parts of it because it was so depressing. (If you’re wondering, it was the extended passage where the main character talks about killing and eating dogs for meat that inspired an actual verbal ejaculation on my part, in the form of a softly muttered “Jesus Christ, Ware, what the fuck . . .”) Woody Brown is still, a grown man, hung up on the first girl he slept with, a sad process in which context the malign neglect of his son serves as only one symptom.

The third section of the book was, in my estimation, the most successful on its own terms: detailing the life of Jordan Lint, an incidental character from the book’s opening passages whose life we see unfold with the cruel and callous precision of a divine watchmaker’s blueprint. Lint is a scion of privilege who grows into the kind of vaguely-defined “businessman” that used to dot the landscape of Cretaceous America. Whatever his job entailed, it was the kind of job that enabled him to embezzle a not insubstantial amount from the firm. This kind of short-sightedness is characteristic of Lint. Born in 1958 and dying in the far future times of 2023, Lint is a model specimen of his generation’s worst traits.

Perhaps that explains why this section held together so well for this reviewer: the thesis propounded by Ware in this section is that, essentially, Lint is given the best of every opportunity that could possibly be offered to a seemingly bright, promising young man in the latter half of the twentieth century. The world is his proverbial oyster, and he responds to this assumed responsibility with a lifetime of churlish resentment. The pleasures and pastimes of youth - you know, the traditional baby boomer preoccupations of sex, drugs, and rock & roll - are sufficiently magnetic that he reacts to the assumption of maturity with the Procrustean irritation of a small child deprived of a bottle. He grows into a man in all ways but the most profound: “you really are a fucking bastard, aren’t you?” asks his second wife towards the end of his section, after the consequences of a lifetime spent in vexatious and sybaritic tantrum have come home to roost in the form of having been abandoned by the children whose abuse he can’t even recall having perpetrated.

That’s the biggest laugh line in the book, incidentally - and it’s a hardy, deep laugh, at the expense of a totem of a generation who failed in every way to deliver on the hopeful promise of their earliest achievements. It’s an earned laugh, and a well-observed one, arriving as it does amidst the collapse of the boomers as a voting bloc and demographic. They could have changed or saved the world, but instead chose to vote for a charismatic con man who promised them that the endless party of their protracted arrested development would continue apace so long as they didn’t bother their pretty little heads wondering where all the bodies were buried.

Of course, said charismatic con man was elected President almost forty years ago. There’s nothing new under the sun, not when it’s morning in America.

This section also features some of Ware’s most interesting cartooning. A dream sequence towards the end of the passage breaks Ware’s endlessly rigorous blocks of square panels into a spread of straight-up expressionism straight out of one of the good issues of Kramers Ergot. It’s a weird and wonderful nightmare sequence, printed entirely in red ink, in which Lint’s childish egocentrism is laid bare for the reader in intense intimate detail.

And it’s these pages to which I find myself returning as I flip through the finished book. They illustrate a principle that, I believe, must be treated as axiomatic when regarding Ware: the man can draw just about anything he sets his mind to. He can draw a pitch-perfect replica of a 1950s science-fiction cover, just like he can do the kind of throwaway gag panels that used to be printed in such magazines, just like he can do abstract pictographic diagrams to represent the way a baby organizes the world around them into discrete categories of “mama” and “not mama.” And sure enough, he can draw human faces well enough that you see the continuity between Lint’s mother’s face and that of the women who he subsequently marries - both the madonnas and whores of his cosmology bear strong resemblance to mama, and I don’t expect anytime soon to find a more potent visual shorthand for the spiritual bankruptcy of selfish men.

If there is one weakness to a work like Rusty Brown it is that there is simply no point in the narrative where it seems as if Ware is anything less than completely in control of precisely what he wants to convey to the reader. That degree of precision - one might even be tempted to call it Dreiserian - can seem cold. Dreiser certainly isn’t to everyone’s tastes, either.

Which brings us neatly back to full circle: you don’t have to like Ware, but you can’t dismiss him, anymore than you could dismiss Dreiser. And that kind of inevitability can’t help but rub anyone the wrong way, which is why you’ve probably never read An American Tragedy.

The final section of the book details the life of Joanne Cole, a teacher at the school where the saga begins. It’s both a well-observed section and, also, strangely flat. Gratifyingly, Ware does not stumble with an African-American protagonist. He observes the effects of racism on Cole’s life with the same acute and unsparing attention as every other phenomena in the book - he knows enough not to make any kind of Bold Statements on the manner, choosing instead simply to show the effects of racism as a kind of steady drip, drip in the background of her life, some days no more noticeable than a few drops, occasionally a tragic deluge. The kind of tedious microagressions that form the background white noise for minorities of all stripes are chronicled in precise detail.

Each viewpoint character throughout the narrative is defined at least in part by their relationship to the art that gives their life meaning. Rusty, obviously, has his comics and television shows, his dad the sci-fi stories he wrote in his youth. Lint wants nothing more than to play rock & roll music, but is shown making only tentative half-steps in that direction. Finally, Joanne Cole is shown as an accomplished banjo player. If there was any point throughout the book where I felt Ware’s heavy hand in the form of affectation, it was the positive terms used throughout to illustrate Joanne’s devotion to her instrument, a devotion that extends both to collecting old sheet music as well as giving instruction at a local music store. Knowing Chris Ware as intimately as we do - I mean, he was in RAW some thirty-odd years ago, for goodness sakes, the man’s proclivities are well known at this late date - I felt the mild annoyance of seeing the deck stacked ever so slightly.

But here again - just when we might think we might have that pesky Ware all wrapped up in a neat bow, he manages to throw a spinner in the works by having Joanne stumble across evidence of the casual racism endemic even to ye olde music world, in the form of sheet music to a song called “Darkey Town.” It’s an acknowledgment that even the most simple and seemingly innocent pastimes of previous days were marred and marked by the country’s original sins, in such a way as to be simply unavoidable for anyone who looks with an honest eye.

If I wanted a phrase to sum Ware’s aesthetic, it might be just that: an honest eye. He even appears himself as a character in the story, an art teacher at the same 1970s middle school attended by Rusty and Jordan. He’s a well-meaning oaf with slight intellectual pretensions, and also a low-key lech on his female students. As awful as that might be it’s a judgment against himself, and it feels as honest as anything else here. Sometimes it be like that.

The past is only an escape if you ignore what actually happened.

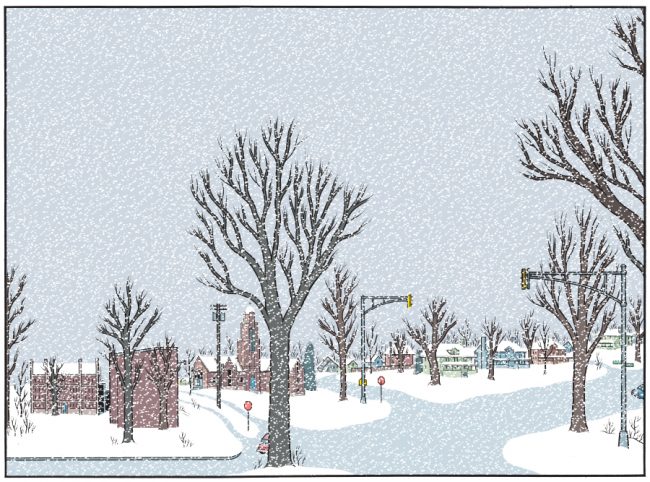

So what’s it all about, then? If I had to put my finger on anything, it’s the idea of Nebraska as a kind of limbo: a flat and cold abyss set down in the heart of the continent right in the middle of where everyone has to go to get to somewhere else. Somewhere more interesting, important, exciting, or just alive. A civilization has been built in the pages of Rusty Brown, populated by empty men and women who wish nothing more than to live their small and sad lives unmolested. That’s rough, yeah. But that’s also America, a country that got started in the act of emptying the land of all the people and places with meaning and history. What rose to replace that meaning and history was a surprisingly brittle order defined by the fiat of arbitrary privilege in some lives over others. Of course it was bound to fall apart: a culture dedicated merely to preserving the right of rich white people to be apart from the run of their fellow men was bound to fall in short order.

At its heart this is a book about the failure of contemporary institutions to provide adequate glue for the society around them. The first chapter takes place in a school, after all, and its hard to imagine a more unwelcoming and stentorian place of learning than the cold and empty halls herein. Rusty is trapped in a personal hell, and so is his dad, and Jordan Lint - although he gets the best view and doesn’t perhaps realize it until the very end of his story, when he feels those infernal flames licking at his coddled feet. This world is failed and flailing, maybe just a generation or two away from complete collapse - but, tellingly, this world is also our world. Ware offers nothing less than a vision of America as a failed state, rotting slowly from the inside out, a rot evidenced most clearly in the simple inability of parents to instill their children with anything resembling a working moral compass.

There’s a part of me that wishes this book wasn’t what it was - that is, despite its flaws, a masterpiece, all 3.6 pounds you can use to stun a burglar in a pinch - but it fucking well is and it would be churlish of me not to recognize that. Look past the author’s reputation and the poisonous overpraise heaped by a literary establishment who perhaps treats Ware with the eager condescension of a trained dancing bear. Maybe he’ll win that Pulitzer this year, or the next. He deserves it, if anyone does, but don’t let that get in the way of actually appreciating the work.

He may be a master, but he’s our master. Long may he wave.