This morning I woke up late, tired from hours spent marching in a Black Lives Matter protest. I nursed a coffee and scrolled past headline after headline about similar protests around the country, and the violence perpetrated by the police and government officials. I felt too depleted to sit at my desk and draw, but I needed to find focus. “Now’s the perfect time to tackle that review of Repulsive Attraction”, I decided.

I put off writing this review for weeks, knowing the task would be difficult. I read the book and set it aside, hoping that my thoughts would crystalize over time. That seems to be my recipe for writing these pieces. Read the work and take notes, let simmer for a week or two until cogent thoughts begin to boil, sit in chair, write. So here I am, struggling to articulate why this book, which looks fantastic and is in line with many of my interests and convictions, misses the mark so spectacularly as a work of political satire.

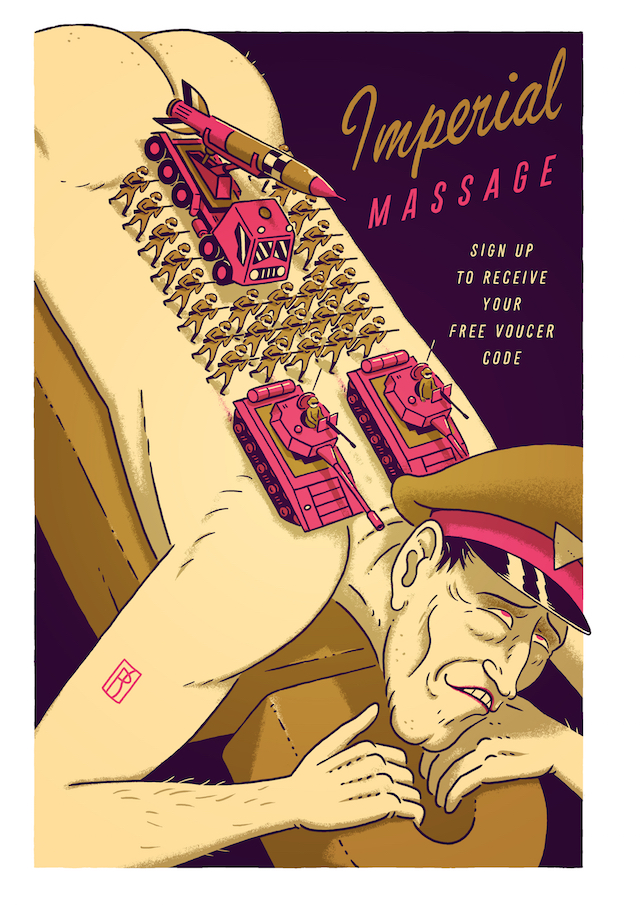

A series of wordless vignettes, Repulsive Attraction is billed in it press release as a “socio & eco critical collection of novels (sic) in a palette of toxic colors. A bastard of dystopian pantomime” Almost every two-or-3 page story, of which there are dozens, represents a scene of contemporary degradation: pollution, cell-phone addiction, homelessness, sexual harassment are all superficially touched on. In “The Descent”, a wealthy industrialist crashes his plane in the jungle and is rescued by benevolent natives, only to turn around following his recovery and build an oil pipeline on their land. In “Capt’n Turkey Nose the Explorer,” a different wealthy industrialist crashes a different plane, is pissed on by a tapir, and the incident is photographed and shared by natives on the social media platform “Nativegram.” In “Unsustainable”, a depressed man orders a gun with which to shoot himself, and we’re shown the carbon footprint that’s created as it’s built and shipped to its final destination. “The Civilized Cultivation of Cup Luwak” depicts the repressive, cruel and wasteful practices behind the cultivation of Kopi Luwak, a luxury drink made from coffee beans harvested from civet feces (look it up.)

My first question for my editor upon reading Repulsive Attraction was “where is the artist, Patrick Steptoe, originally from?” The representation of Native Americans as “noble savages” and people of African descent as blackface caricatures indicated to me that the work was European in origin, and sure enough, Steptoe is Danish. For some reason, I suspect it may have to do with the European colonial legacy in Africa and the cultural worship of artists like Herge, Joost Swarte and R. Crumb, but some younger white European artists, even those who consider themselves to be progressive, are still using racial caricatures in their work, a fact that I find despicable. When American cartoonist friends of mine traveled to the Bilbolbul comics festival in Bologna in 2018, they were shocked to learn that the festival it takes its name from a character in a popular Italian newspaper strip, a blackface caricature of an African child created by the artist Attilio Mussino in 1911. Supposed cultural critics like Spanish enfant terrible Joan Cornella and the German painter and installation artist Boris Hoppek are using the imagery as well.

My first question for my editor upon reading Repulsive Attraction was “where is the artist, Patrick Steptoe, originally from?” The representation of Native Americans as “noble savages” and people of African descent as blackface caricatures indicated to me that the work was European in origin, and sure enough, Steptoe is Danish. For some reason, I suspect it may have to do with the European colonial legacy in Africa and the cultural worship of artists like Herge, Joost Swarte and R. Crumb, but some younger white European artists, even those who consider themselves to be progressive, are still using racial caricatures in their work, a fact that I find despicable. When American cartoonist friends of mine traveled to the Bilbolbul comics festival in Bologna in 2018, they were shocked to learn that the festival it takes its name from a character in a popular Italian newspaper strip, a blackface caricature of an African child created by the artist Attilio Mussino in 1911. Supposed cultural critics like Spanish enfant terrible Joan Cornella and the German painter and installation artist Boris Hoppek are using the imagery as well.

In her introduction to her book-length essay The Art of Cruelty, cultural critic Maggie Nelson writes that “by now, it is something of a commonplace to say that twentieth-century art movements were veritably obsessed with diagnosing injustice and alienation, and prescribing various shock and awe treatments to cure us of them-a method Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke usefully, if revoltingly, described in a 2007 interview as “raping the viewer into independence.” She goes on to list the ills of which a certain school of artists think their audience must be forcefully made aware, using such shock tactics: “alienation from our labor, a fatal rift with nature, being lost in a forest of simulations, being deformed by systems such as capitalism and patriarchy, Westernization, not enough Westernization etc.” Not coincidentally, these are the ills catalogued in Repressive Attraction.

Activist movements need artists to lay bare the hypocrisy of capitalism and authoritarian regimes, but the artists must go a step further, and remind us why it’s worth risking everything to fight back. Emory Douglas created a unified, uplifting aesthetic for the Black Panther party in the pages of their newspaper, one of power and community. David Wojnarowicz’s Reagan-era memoir Close to the Knives is one of the most affecting works of political art I’ve ever encountered and it is deeply personal, a howl of pain, outrage and despair, and yet Wojnarowicz’s drive to create in the face of insurmountable odds is a beacon to others in the darkness. Eleanor Davis’s stunning The Hard Tomorrow grapples intimately with its characters-their dreams and desires, as they struggle to navigate a dystopian America in which their very existence is criminalized.

Activist movements need artists to lay bare the hypocrisy of capitalism and authoritarian regimes, but the artists must go a step further, and remind us why it’s worth risking everything to fight back. Emory Douglas created a unified, uplifting aesthetic for the Black Panther party in the pages of their newspaper, one of power and community. David Wojnarowicz’s Reagan-era memoir Close to the Knives is one of the most affecting works of political art I’ve ever encountered and it is deeply personal, a howl of pain, outrage and despair, and yet Wojnarowicz’s drive to create in the face of insurmountable odds is a beacon to others in the darkness. Eleanor Davis’s stunning The Hard Tomorrow grapples intimately with its characters-their dreams and desires, as they struggle to navigate a dystopian America in which their very existence is criminalized.

By contrast, Repulsive Attraction is a parade of stylized suffering. To be fair, I was radicalized by punk music, and artists like Winston Smith, whose album art for the Dead Kennedys juxtaposed religious iconography, imagery from advertising and graphic depictions of the horrors of war-not exactly subtle stuff. Repulsive Attraction is aesthetically informed by punk and also by the imagery of horror comics, both of which I absolutely adore. It has a bit of the psychedelic sensibility of French artist Philippe Caza, who worked with Heavy Metal, and of the Spanish artist Carlos Ezquerra, an alum of 2000 AD, both publications which Steptoe has cited as influences. The “toxic colors” are wildly successful-an object lesson in the power of limited palette-and although I’m a despiser of digital drawing, this classic clear-line cartooning seems to have been flawlessly executed on a tablet. It’s eye-catching and delirious in the best way, and it speaks to the book’s potential-there are ingredients here which, if used in a different quantity and sequence, could make a much tastier meal.

The best story in the 43-page collection, "Medi Gora", is a fantasy story set in the distant past. A young woman grieving her miscarriage creates a homunculus to replace her lost child, an act that brings her peace and resolution. Furious when they discover she’s been dabbling in the occult, her fellow villagers execute her for witchcraft. Here, Steptoe creates a character with whom we can empathize, a hero whose emotional life is slightly more fleshed out and therefore worthy of our time and interest.

The best story in the 43-page collection, "Medi Gora", is a fantasy story set in the distant past. A young woman grieving her miscarriage creates a homunculus to replace her lost child, an act that brings her peace and resolution. Furious when they discover she’s been dabbling in the occult, her fellow villagers execute her for witchcraft. Here, Steptoe creates a character with whom we can empathize, a hero whose emotional life is slightly more fleshed out and therefore worthy of our time and interest.

At the end of the book, Steptoe introduces himself in a short 2 page autobiographical piece, titled "Afterwords". We learn that the artist studied fashion design and worked a succession of jobs in the industry but became disillusioned with fast fashion and corporate culture. He quit his job and began an ultimately unsuccessful quest to support himself and his family as a freelancer, working first as a competitive sandcastle builder and then in animation. He closes the piece by stating that “if you expect some kind of morale (sic) to this tragic farce: well, I can personally assure you that chasing your lame dreams doesn’t pay off in the modern capitalistic society.”

The moral as far as I’m concerned is this: write what you know. I often see very successful writers decrying this kind of catch-all how-to-write advice, and I agree that there are no magic-bullet writing tips, but what I wouldn’t give to have read a book about a character struggling to make a living on the competitive sandcastle circuit, or a book about a design instructor trying to reconcile his disdain for the fast fashion industry with his imperative to feed his growing family. These small personal stories are universal, and devastating, and they’re a reminder that workers deserve and should hope for so much more than the scraps we’re competing for.