The place is a future metropolis of hover cars and skyscrapers, metallic cleanliness and scientific advancement, the optimistic cartoon technocracy which science fiction authors dreamt of perhaps more often in the utopian infancy of the genre than today. In pursuit of knowledge with wonderful machinery and a towering intellect at his disposal, a brilliant astronomer makes an incredible discovery, a heretofore unknown star, shining brightly not far from our own solar system. Lauded by the public and deeply proud of his contribution to the study of the universe, he names the star after his daughter. Unfortunately for him, he has failed to perceive the full and dreadful significance of his discovery. The newfound star is an evil star, a disaster.[1] The star, a planet, now rockets towards the earth at a breakneck pace, stopping just short of collision. As the seemingly living star hovers above the earth, the world’s ecosystem and society alike are driven rapidly into chaos. At the center of this doom and destruction the fervor of a dying, maddened human race is turned at once to the star and to a girl, known by one name: Remina.

Remina (now referring to the title of the manga itself, rather than to the planet or the girl) is the second longform work by Junji Ito begun in the wake of the conclusion of his iconic serial Uzumaki.[2] Like the prior series Gyo, Ito attempts to sustain the apocalyptic intensity and scale of Uzumaki’s explosive finale, but with a more consistent narrative throughline rather than the accumulating thematic threads of interconnected stories that ultimately build into something comprehensive and total. The two longform works of Ito’s 2000s “middle” period both gesture toward the scope and tenor of the disaster movie and the action horror blockbuster, albeit with much more imaginative and horrendously specific imagery than an archetypical Roland Emerich movie where a big wave or a volcano causes epic problems for a population.

Whereas Gyo adopts a charmingly improvisational tenor, a gross-out nightmare riff on Jaws building rapidly to an absurd, sprawling scale, Remina is more structured, even restrained, a decompressed short story playing out over ~250 pages of cosmic horror and austere pulp. It’s a bit pitchy: this is probably the first of Junji Ito’s “major” works to feel padded, leaning on perfunctory genre situations that a pre-code EC horror story would have ploughed through in 12 pages, at most.[3] Because Ito’s characters have always been cyphers to a certain extent, one begins to grow impatient for this story to move along and get to the point so we can enjoy more abject imagery, a rare problem for the enthusiastic reader of Ito’s prior work where the creativity of the scares, the atmosphere and the (slight) psychologies of the characters are so deftly interwoven as to leave a profound and intense impression that develops and deepens as one lingers in the accumulating weight of several stories, something grotesque and vivid to haunt you. Remina endeavors to present a single sustained narrative vision of intensity and scale and is somewhat weaker for it.

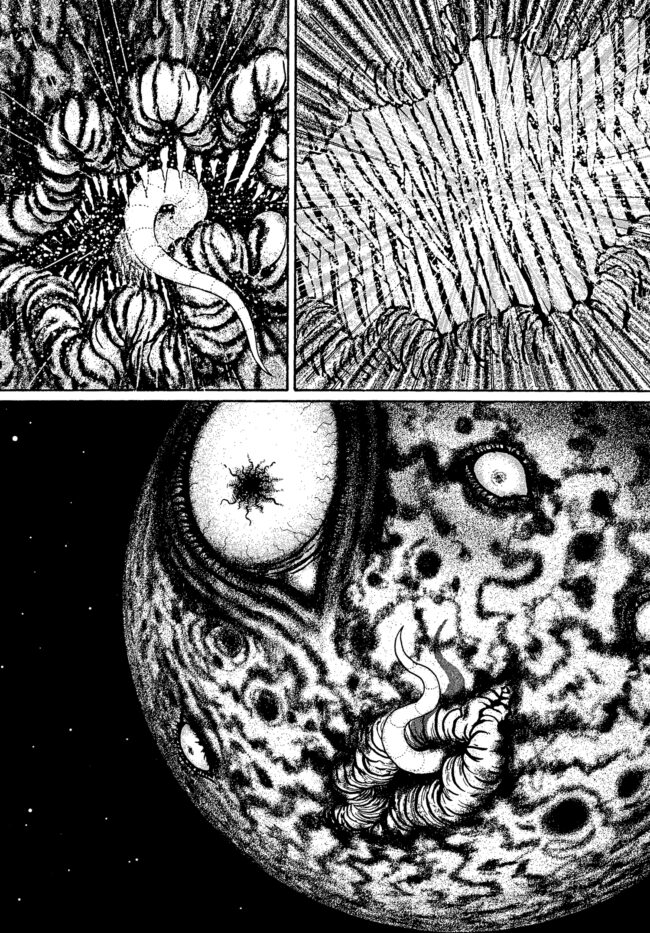

But with all of these qualifications made, that single vision is one of Ito’s most vivid and striking. Remina, the hellstar, the killer planet, all pustules and scabs and giant fungi, with its leering eye and lasciviously hungry tongue, is nothing short of spectacular horror imagery. The planet Remina is the fear, the end, the disease and muck and every thing we avoid knowing that it will be the death of us and everyone we know, and not only is that fearful entity, that portent of our collective doom and ignorance, as grotesque and horrendous as we all know it is collectively but deeply ridiculous at the same time as it leers at us giggling as it lets us know that it is coming and that we cannot look away forever. The planet Remina is pure and total obscenity as much as it is an inevitability, the ideal mascot for the destruction of humanity. I genuinely wonder if Ito may have been inspired by Hildegard von Bingen’s vision of the antichrist in Scivias, a similarly vulgar head of worldly muck and obscene glee portending the end of days.

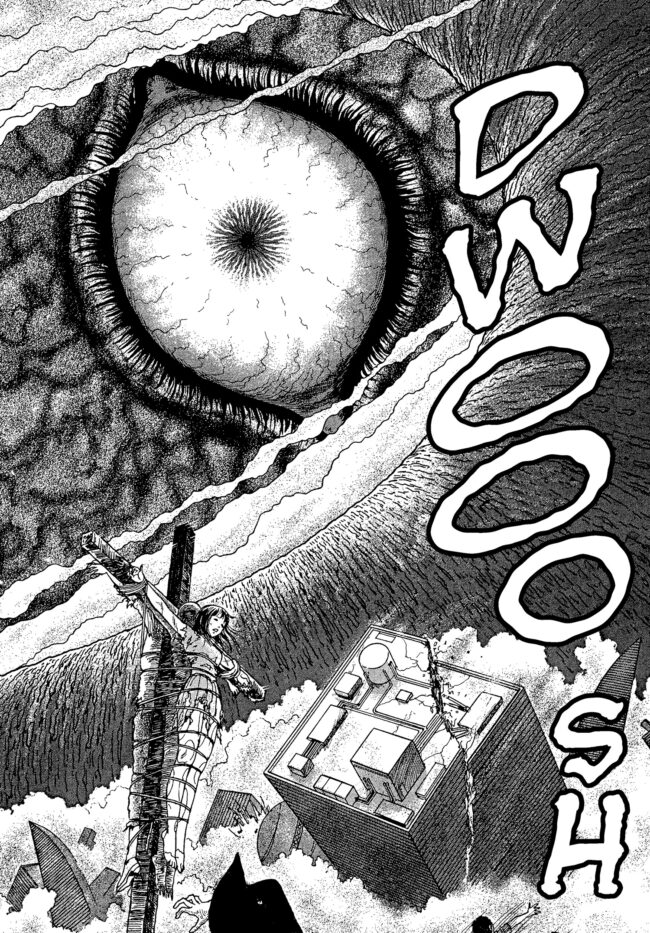

On the raw imagery level (a level that should not ever be neglected in a visual medium), the visceral horror of Remina comes not only from the weird grotesque abjection of its cosmic centerpiece -- in this work, Ito, traffics in the ghoulish violence of American pulp fiction that kept the likes Fred Wertham up and night fearing for the safety of children. Angry mobs, led by a fervent mysterious cult leader in hooded Klan robes pursue the girl Remina with religious fervor, seeking to make her a martyr and punish equally all who would protect her and any who would give her death an unworthy ignobility. There are witch burnings, crucifixions, whippings, and beatings of captive innocents by ravenous mobs led by a monstrous, sometimes lizard-like Klansman with leering eyes and a grotesque tongue not unlike the planet looming above them. This is more “traditional” genre horror iconography than what Ito normally trades in[4] -- even if you haven’t been so perverted as to immediately think of your favorite grizzly 40s/50s horror comic cover, sanitized versions of these images make their way quite intensely into the Universal monster movies and such -- but it’s also a more human horror, a more possible horror, a horror which can happen, and indeed has happened.[5] With these terrestrial and celestial poles of terror aligned, the planet looming above and the crazed mobs in constant motion lends the work a suffocating, memorable intensity.

Squeezed between this vice of heaven and earth, Remina the girl is caught in a drama of persecution in which she plays a secondary role to her name. From the beginning, she is a special girl, not because of anything intrinsic to her but because her father and his accomplishments have forced her into the spotlight, defined as an icon by his vain correlation of her name with his discovery in the oppressive name of parental “love.”[6] The disaster of her father’s vanity is immediate, not only because the planet immediately turns out to be a living monster out to destroy the Earth but because in sharing her name, he has denied his daughter Remina the chance to ever just be herself. She is predestined to be at the center of tragedy, to be seen as the cause of this greater force, its companion, or idealized absurdly for her unfair persecution, even fetishized. Most reach out to kill her, some take her hand to save her, to all she is an icon of something beyond anything she ever chose to be, anything she ever got to feel, an idol who never quite got to be a person. It gets brought up fairly often by people who haven’t put much thought into why a lot of women like horror that much of Ito’s classic work ran in a horror magazine targeted at women, Monthly Halloween. I think that anyone who wants to offer an opinion on the peculiarity of horror's appeal to women should think carefully and at least read House of Psychotic Women before speaking,[7] but I will say tension which the central drama of Remina operates on, of intense persecution and vulnerability coupled with the glamor of being recognized and known by literally everyone, is as much the stuff of shojo manga as it is of horror, and I strongly doubt I will be finding myself in a minority of women readers who find this work immensely appealing and (dare I say it?) relatable.

[the following two paragraphs describe the end of the comic in great detail]

But of course the most spectacular and memorable things about Remina, the thing you’ve probably heard the most about if you were reading up on Ito in a horror manga subreddit or somesuch, is it’s unbelievably great climax -- finally making good on the threat that Marvel comics has been waving at us since the Galactus trilogy: the end of the world at the hands of a hungering cosmic being, i.e. the planet Remina eats the Earth. In an absolutely inimitable sequence of splashes, we see the planet carried by Remina’s lolling tongue into its gargantuan maw. The Earth is devoured, yes, but it is less a scene of violent digestion as it is one of consumption and absorption. Swallowed whole, the Earth seems to almost fade into the putrid oblivion of planet Remina’s jaws, its teeth -- if they can be called that -- massive needlelike tendrils of foggy screentone, a fade to white while the dark mass enclosing slowly heaves shut. And the face of planet Remina -- it’s so goofy! The clamor of the end of days is drawn silent, and this silly, gross destroying thing cheerfully glides away licking its lips. Finally it is done.

However, both Remina’s survive. Remina the girl has made it into a shelter, adrift in space, with a few of the people who protected her, a couple of strangers, and enough food to last “maybe a year.” Her parents and everyone she knew, literally the entire world is dead and gone. These people might live. They might die. It might be a few seconds, it might be eternity. They are safe right now and there’s no knowing what’s next anymore. But for Remina, the horrific tragedy is that she has come of age without anyone who knows her, without anything to teach her who she is, was, might be. The terminus of her adolescence has been spent running, being carried, being captured and escaping, watching in terror as literally everything and everyone she once knew or thought she knew ceased violently. She was persecuted and endured, but what’s left? She never had a beginning. All she has left of herself is a name shared by destruction incarnate -- maybe she really is the thing that attracted that hellstar to the Earth, the cause of all that is vile. And if that is not the case, if she isn’t the curse of the human race incarnate, is that any better? That name, Remina, is all she has. Peering out behind the reinforced windows of the little shelter holding the little life that remains, Remina gazes sadly into the yawning abyss of space. Her sad, blank expression in the closing pages of this book is not one the reader is allowed to conclusively define -- the only words she has are the people that she knew and lost. But I think she wonders if the absent planet Earth was a place she ever had lived. With that world gone, will she ever be alive? Can someone who has never been able to live even die?