If you have heard of this comic, you have probably heard that it is difficult. Its creator, Zak Sally -- and I don't use “creator” here simply to denote a writer/artist, but also the publisher, printer, and primary distributor of the work -- has not hesitated to warn potential readers that this new installment of his one-man anthology is “NOT for everyone,” and that “if you are looking for a passive, easy reading experience, this is not it.” So says what I've come to call the solicitation text, which I really cannot recommend highly enough – so perfectly does it excerpt the printed work's themes and obsessions I'd begun to think of it as part of the comic itself, like an overture, even before Sally abruptly announced to Tom Spurgeon, exactly one month after the initial Risograph printing, that he would be releasing the entire contents of the issue online. Now, freed of the constraints of paper and sewn together with small clicks, a truly holistic experience is possible, its author's explication of the consumer mores surrounding "handmade" objects standing just to one side of the resolution to what one can only presume was a continuing debate.

I've not read the online version, though; it's not even up yet, as of this writing. I only plan to ever address the print edition here, because most of the interest and the difficulty I have found in this book are native to its printed state. And know too that it is not "difficult" in the sense that its motives are obscure - Sally summed those up to Spurgeon in eight words: “I kind of realized that I'm fucking done.”

No, the difficulty of Recidivist is of a tactile sort. It is one of two works I found at the recent Comic Arts Brooklyn to purposefully incorporate a level of physical strain into the very act of reading. The other one was John Pham's Epoxy 5, which is set up like a slow descent through layers of fiction. First, there is the 'main' story, i.e. the actual pages of the (roughly) magazine-sized comic titled “Epoxy 5”, which behaves like a typical, decompressed mangaesque serial chapter, wide with looming environments, and light on text. Bound into that -- as in, physically conjoined with “Epoxy 5” -- is a smaller minicomic, “Jay & Kay”, a John Stanley-like suite of gag stories which distance the reader, a bit, through the inclusion of fake ads and the like, as if it's not a virtual world to get lost in, a la “Epoxy 5”, but an object you've somehow found, seeking in part to sell you other things you cannot buy. And then, bound into that, is a very small publication: “Cool Magazine”, an item from inside the world of the (somewhat) larger (mini)comic, filled with teeny-tiny articles and several bonus inserts of its own, one of them roughly the size of a postage stamp. Basically, the further you try to sink into Pham's world, into fictions within fictions, the more text-heavy the material gets, and the harder the text is to discern without squinting or resorting to optical aids - as if, metaphorically, you're trying to identify something from a nagging distance.

Recidivist is a lot more aggressive, and a little more complex. Four stories are included, along with several standalone recurring narrative images, and also a CD.

There are just over 21 minutes' worth of sound on the disc, which my VLC player helpfully identifies as the 2005 CD-R release Buried by Fog from the Detroit noise outfit Wolf Eyes. The sound, however, is not that of Buried by Fog, which might be described as finding yourself strapped to a misfiring centrifuge on a busy airport runway, the force of gravity causing the heavens to occasionally explode into cosmic roars while the ground crew marshals buzz-saws to free you, with little success. What Sally has “recorded” (as his credit reads) is instead high and whining, as if a thin plank of metal is being honed, eternally, on a crystal wheel. It is both divine and painful at first - ripped through with drill screams of feedback, as if you'd wandered into a cold, tall spacecraft only to discover that the aliens had already set up their dissection table, and then the walls fall down and the lights turn red and the whine becomes dull – but maybe you've simply gotten used to it by then, as a character in this story.

I'm making reference to story, because the disc Sally has recorded is semi-diegetic, which is to say that maybe it can be heard inside Recidivist, and maybe not, but the appearance of the CD itself recurs within the comic as an icon of gnawing, ambient worry. That it might be literally a recycled CD is apropos, because these sounds are overwriting everything. If you look closely up at the top of this page, you can see that the CD's imprint forms the cover image. A black alternate cover reveals a small square inside the circle, about which more will be said later; the square is also visible on the inside-front cover. And then, the first page:

This composition is seen three times in the comic: once at the start, once at the end, and once toward the middle, always with the long-nosed human figure standing in the foreground, always with the doom vortex/crystal wheel/free CD hovering in the background, and always with a tortured narration printed at the bottom. From this text, on page one, you can immediately discern the unwavering focus of this book: irrelevance; obsolescence. It is the cry of a man -- all identifiable adult characters in the book are men -- who once knew purpose, and perhaps enjoyed some renown, or at least some give-and-take with fellow travelers, but now has realized that his time is past, and his words are ignored. And yet, he still must live, hearing the tearing of feedback drills from heaven. Fuck.

Every subsequent page of this Recidivist is a variation on this theme. Sally calls it “a pretty indicative document of what and who [I] am, and where [I've] ended up; from the content to the production to every damn thing you can name.” I believe him. This reads like a completely internal document, ejected by a man of many years' print experience, onto the sidewalk of an increasingly less-male, youthful, digital scene. This is private algebra. But what makes it interesting is that Sally and his narrators don't, can't, won't identify a cause for their despair – instead, efforts are made to capture the texture of despair itself through aggregating metaphors, and often the printing process itself.

I will now describe the four “stories” included in this comic, such as they are:

1. “Scratch, Scrape.”

A man has lost some teeth “to senseless stupidity.” He has kept them in a jar on his desk, because they used to be something inside him, or maybe they remind him of the ephemeral nature of things. Now he has lost them; he couldn't put them back in before, but now he can't even look at them.

Most of the story is told by an arch narrator, his words superimposed over the frantic action of the searching man. The narration addresses the man's futile attempts to catalog and arrange his life. This man, though, has been left behind, and now he is desperate to locate the next angle to keep himself going, to retain a sense of relevance. “A single speck that somehow contains just enough faith and hope to keep you afloat amidst all this goddamn garbage and noise.”

The man finds his teeth, which are tiny sparkles of metallic silver ink, which shine on the page in vivid contrast to the black ink of the narration, which tend to drown against the darker portions of the page, as white subtitles would against a movie character's white shirt. The man is apparently hard of hearing, but every so often he gazes intently at the ground, looking for teeth, and we can see through an ambiguous point of view that the black letters of the narration are themselves partially diegetic, and are casting distant blue shadows on the floor.

We can conclude from this that the man has not yet understood the futility of his efforts, but he will. I identified the narrator as a male, because I think it is him.

2. “Revenge”

Again, a narrator accuses a male character – the man's face is now obscured, in the few panels where his body is present. Mostly we see still-lifes of tools, cloth, water, paper, teeth (again, now very realistic).

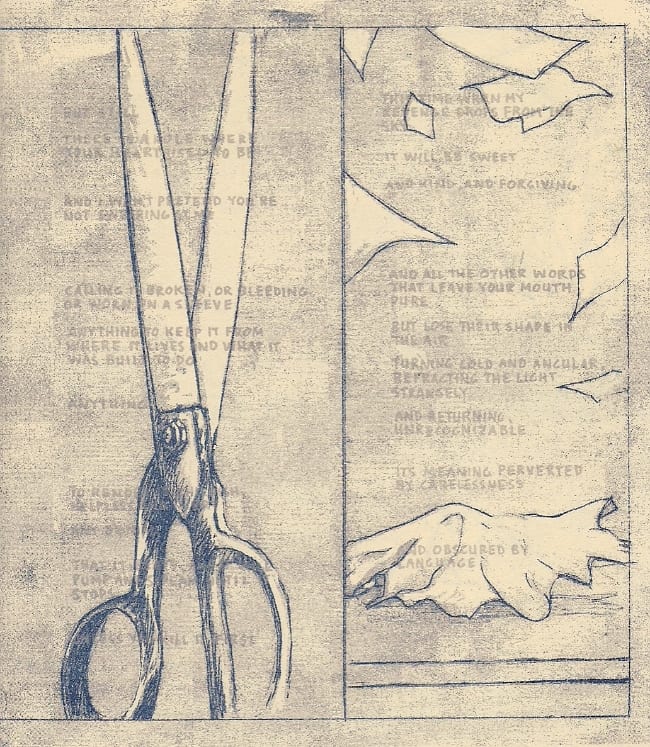

All of the narration is printed with the same metallic silver ink as the teeth in the prior story. Against the very light blue-gray scheme of the drawings, the words are extremely difficult to discern without rocking the book back and forth, casting and denying reflective light depending on how the drawings are impeding legibility; the ink can alternately darken or shimmer, and at times you need to switch tracks mid-word.

The narration castigates the man's folly; he has imagined what he has done with his life to be frivolous, as an excuse for fucking up all the time. “Something to hide behind. Like a ghost.” The narrator details, at some length, how he will have his revenge, by seizing shit with both hands. “I had to start believing in ghosts, because I see them everywhere I go, now.” The words are spectral. Ghostly. If the narrator and the man are again one and the same, he had begun to discern the language of the situation, sitting with a napkin over his face.

3. “Unhome.”

And so, having witnessed two stages of dawning realization, the fusion begins.

Only the first and last pages of this story blend narration and literal depictions. Mostly, every left-facing page depicts the noise spiral/CD, with text printed twice upon it: once in black ink, and once in metallic silver. The two layers are not perfectly registered; “the riso has anywhere from a 16th to 1/8th inch variance on any given sheet, and when you are lining up 6 colors, each on a different pass, it'll do that,” says Sally, in the solicitation.

A digital edition will annihilate this variance. It will create a "master" version, whereas every printed copy will be somewhat different, which I find to add a useful element of caprice to the oft-repeated, self-flagellating counter-intuitive pep talks within. Will, for example, the two inks cohere, so that I cannot resort to tilting the book and dimming the metal as much as possible, thus relying on the outlines of black against the yellow spiral?

And what to make of this? Even as the text documents the severe angst of a life in flux -- “But what if this is home right now? What if this is where you will live from this minute forward, and this constant buzzing in your ears isn't ghosts like you thought but the sound of something hurtling toward you, full bore.” -- the ghost/buzz/noise/circle is invaded by a square, its shape distorted and its polarity reversed, causing this reader to flip his approach and gradually rely more on shining silver rather then black against the visual noise, with the black ink finally subsumed entirely.

Some of the narration, in the middle, is utterly incomprehensible. The metallic ink just isn't applied in a way that adequately picks up enough light to allow the words to be read.

But then, ask why when Gary Panter presents unreadable captions in Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, as a drawn function, it is at least theoretically art, and why when ink is not adequately applied to paper it is, ipso facto, a mechanical failure and an objective fault: a product flaw. A refrigerator that has failed to keep food cold. YOU HAD ONE JOB, art made for reproduction, and that was to reproduce!

Again, the paratext is informative. From the solicitation: “[I]'ve never seen a book like that, and (mostly) [I] did that on purpose, for a specific reason.” Note the parenthetical – total intentionality is specifically disclaimed here. For many artists, if we are realistic, it is inferred.

And then we should ask: if we are interested in experimental work, is there not some necessity for an element of failure? Because an experiment denied the potential for failure is not an experiment, but a feat.

On the right-facing pages are wordless drawings, full-page splashes, depicting a man not unlike the luckless fool from “Scratch, Scrape.” He is pursuing a silvery sparkle, a la one of his teeth. As the circle begins to give way to the square on the left-facing pages, the sparkle dives down the man's throat, inhabiting him; blowing him up like a balloon and whisking him away to parts unknown: delightful, undulating landscapes under lemon skies, really lovely drawings, and finally a pool of dark water.

By this point, the circle and, analogously, its damnable hum, has been obliterated by the square; the pages are dark, and the text is very readable in perfect, shining type. The path is certain. The narrator must sink into this new world. Physically, he may die, but god is there room for unlikely results on these pages.

4. [untitled]

This is a wordless story told with the utmost clarity, about which nothing needs be said.

–

“I learned to love it,” the first, long-nosed man remarks on the final, recurring composition. He has discovered the pleasures of irrelevance at last; you are free to do whatever you want. To slip behind people and catch them off guard. “This time, I'm leaving something behind, whether you find it or not just to haunt you.”

The results are in your hands. Everything is squared away.