Dennis Eichhorn made his name in the early '90s with his two-fisted autobio series, Real Stuff. He seemed to be a sort of mirror image to Harvey Pekar, as both men were writers who employed a number of alt-cartoonists to depict stories from their everyday lives, as well as their checkered pasts. In Pekar's case, of course, he sought to draw poignancy from the mundane and quotidian while exploring his emotions, intellectual interests and the interesting people he happened to work with and frequently befriend. Nothing much "happened" in those stories in a kinetic, narrative sense, other than a particular thought or anecdote being relayed in a memorable fashion. Eichhorn, on the other hand, has led an extraordinarily colorful life and isn't afraid to share every detail with his readers.

Indeed, every Eichhorn story includes either a fight or some threat of violence, a wild drug sequence, a graphic and frequently hilarious sex scene, a recounting of some interesting and generally unbalanced person he happened to encounter, or some combination thereof. What has always made his comics great is the way Eichhorn never takes himself seriously. He simply has an uncanny knack for telling a great yarn and playing to each of his artist's particular strengths. Whether or not every detail is 100% true is less important than each story being entertaining and compelling. After several years out of comics, Tom Van Deusen of micropublisher Poochie Press ran a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for a revival of Eichhorn's series with a stable of artists both old and new. Eichhorn stalwarts like Jim Blanchard, Pat Moriarity, and Mary Fleener are all here, but so are young artists like Noah Van Sciver, Max Clotfelter, and Ben Horak. There's a sense in which Eichhorn's writing is formulaic and even predictable, but it's a formula that he perfected. No other autobiographical comics writer has Eichhorn's knack for producing sheer entertainment. He's not a deep thinker like Pekar, nor is he much interested in navel-gazing. Instead, he simply wants to share every interesting observation about the world around him that he's experienced.

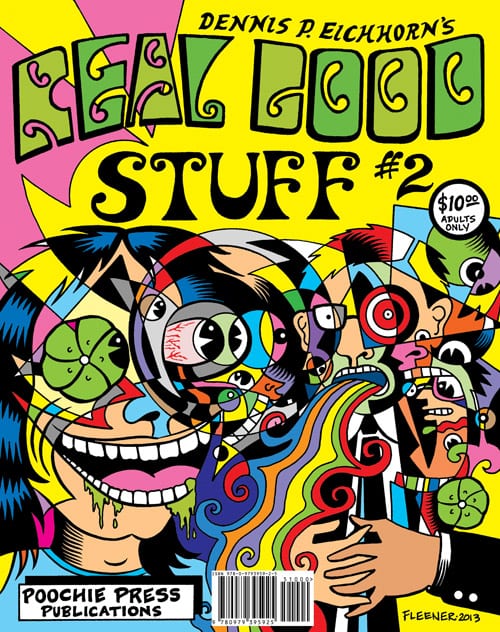

Eichhorn sticks to his tried-and-true formula in this flip-book, 66-page chunk of alt-comics. It's a perfect length for an Eichhorn project, as the sheer readability of his comics has always left me wanting more as a reader, but a longer comic might have started to feel repetitive. The Real Stuff collection published by Caleb Wright's Swifty Morales Press circumvented that problem by putting the stories in chronological order according to Eichhorn's age in each story, but such an approach would be difficult with new material. There are several stand-out stories here, thanks in part to the subject matter and in part to the ways that the individual artists brought the stories to life. However, there are also smaller contributions that are worth mentioning. Mary Fleener's cover for #2 is a vivid, funny example of her over-the-top "cubismo" style, detailing the results of a peyote trip in a colorful, distorted manner. The two portraits that Jim Blanchard drew are excellent examples of his pointillist style, bringing to life some especially colorful characters. Ben Horak's rubbery drawing is a fun match for the freewheeling table of contents.

Moriarity's art for "Gone But Not Forgotten" details the time that Eichhorn went out in search of downers with the drummer for the Plasmatics (a mohawked, tattooed individual who is drawn by Moriarity as looking like a sort of mutant). It's a classic Eichhorn story: an encounter with a rock figure, an element of danger, somewhat crazy women figuring into things, a quest for drugs, and Eichhorn managing to get out of harm's way just in time. "The Hate Man Cometh" is the prototypical Eichhorn profile of someone he finds interesting; in this case, it's a drop-out in the Berkeley area who preached an oddly affecting philosophy of compassionate hate. Van Deusen's style mixes naturalism with a grotesque, rubbery quality that is a snug fit for this larger-than-life character.

The second issue is even stronger in terms of its contributors. Fleener opens with a story about a stage manager who schmoozed acquaintances by giving them a guitar pick supposedly used by Eric Clapton, until Eichhorn realized he'd been had. "Eligibility" is drawn by Van Sciver, another young cartoonist seemingly born to draw an Eichhorn story. Here, Eichhorn dips into one of my favorite of his storytelling wells: an anecdote from one of his many, varied and weird occupations. This one involved going door-to-door to make sure that food stamp recipients had a proper cooking implement and a house they were renting. Naturally, one man he interviews has a giant bag full of peyote buttons, and one thing leads to another. As per usual, Eichhorn manages to end this scratchily drawn, sweaty story with a gag (Van Sciver nails it).

Clotfelter's "Christian Duty" is a combination of a job story and a weirdo story, as Eichhorn's account of being a taxi driver who frequently has to drive around a violent, unbalanced ex-Navy SEAL who loves nothing else but to get drunk and terrorize other bar patrons. Clotfelter's thick, exaggerated character designs (replete with thick, bushy eyebrows, toothy mouths, and flop sweat) are yet another ideal match for a story with an air of danger that's avoided at the last moment. Finally, Aaron Lange's "Topsy-Turvy" and "Viagara Falls" are the other stories of great visual interest. He's the go-to artist for explicit sex scenes in this comic, employing a flat, visually blasé style that then stuns the reader with graphic sex scenes out of the blue. Both stories are played entirely for laughs, adding a weird tension between the pornographic quality of the art and the eventual gag at the end. In both instances, Lange offers a palate-cleaning jolt to the reader's aesthetic palate.

One gets the sense that Eichhorn puts a lot of trust into his individual artists to run with his stories in their own style. Like Pekar, he has a sense of when to really strike the reader with a visually provocative style, and when to hold back with a more conventional storytelling approach that lets his writing do much of the work. Even the less striking stylists, like Sean Hurley and Michael Arnold, don't let Eichhorn or the reader down; both get across the story that Eichhorn wants to tell. I was somewhat less enamored of the scratchy, somewhat incoherent work of Paul Ollswang, and the 1995 date attached to this story points to this one as something that didn't quite make it into the original series. Eichhorn's autobiographical storytelling is as fresh, funny, and outrageous as ever, and I hope the series is successful enough to encourage him to continue.