Ces bandes dessinees ne sont pas une pipe non plus

“Can Johnny come out and play?”

“Why, Billy, you know Johnny’s a quadriplegic.”

“Yeah, but we want to use him for third base.”

-Example of side-splitting humor, circa 8th grade (1956)

“Sick humor,” they called it then – usually in news magazines’ articles on civilization’s fall. At the high end of this abomination perched Mort Sahl and Lennie Bruce. At the low squatted Johnny. For a 14-year-old humorist, it was neither as beyond the pale (i.e. necessary to conceal from parents) as “dirty” jokes, nor as transgressive (i.e. usually requiring the preface “I’m not prejudiced but...”) as jokes about race or religion, but it served its purveyor similarly. Its daring elevated him above his peers. Its expansion of the possible increased his own understanding of the world. So did the absence of any lightening bolt striking him down.

In December 1969, Henry Beard, a blue-blooded recent graduate of Harvard University, who had germinated in this humor’s effluence, wrote letters soliciting contributions for a magazine was preparing to co-found. One recipient was a 43-year-old, devout Catholic of Portugese ancestry, born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and in whose vicinity he had lived most of his life since. He had enlisted in the navy, at 17, but had been discharged after contracting rheumatic fever during basic training. Deciding he did not have what it took to succeed as a writer, he had studied cartooning at what would become New York City’s School of Visual Arts. During the 1950s and ‘60s, he had contributed regularly to Hi-Fi Music Review (later Stereo Review), Electronics Illustrated, and, less regularly Esquire, Look, Playboy, and TV Guide, with work that drew comparison to Charles Addams, VIP, and Gahan Wilson. He had published one collection of cartoons, Spitting on the Sheriff (1966) and illustrated Strictly Personal, a compilation of “racy” classified ads by Leo Guild, whose oeuvre which included such titles as The Loves of Liberace and Street Ho’s, would win him designation as “The Worst Pulp Novelist Ever.”

The target audience for Beard’s magazine was that portion of America’s youth amenable to cultural revolution. The cartoonist’s politics leaned markedly to this market’s right. His head shot, bald, fleshy faced, and thickly eyeglassed, would not have won space from Che or Dylan on its dorm or crash pads’ walls. He did not smoke or snort his stimulants. He played Russ Colombo and Bing Crosby on his stereo, not Doors and Stones. But his humor, which mocked blindness, cannibalism, castration, defecation, enemas, farts, hemorrhoids, herpes, homosexuals, infanticide, menstruation, necrophilia, racist caricatures, sado-masochism, urination, and vomit fit the young like a lead-knuckled glove. I do not mean to imply that Beard’s projected readership reveled in bodily fluids and physical abnormality, but, hey, anything that shocked the elders... Storm the Bastille; kill your father; ridicule the handicapped... You chose your shackle, and you cast it aside.

Charles Rodrigues remained with The National Lampoon for 24 years.

Charles Rodrigues remained with The National Lampoon for 24 years.

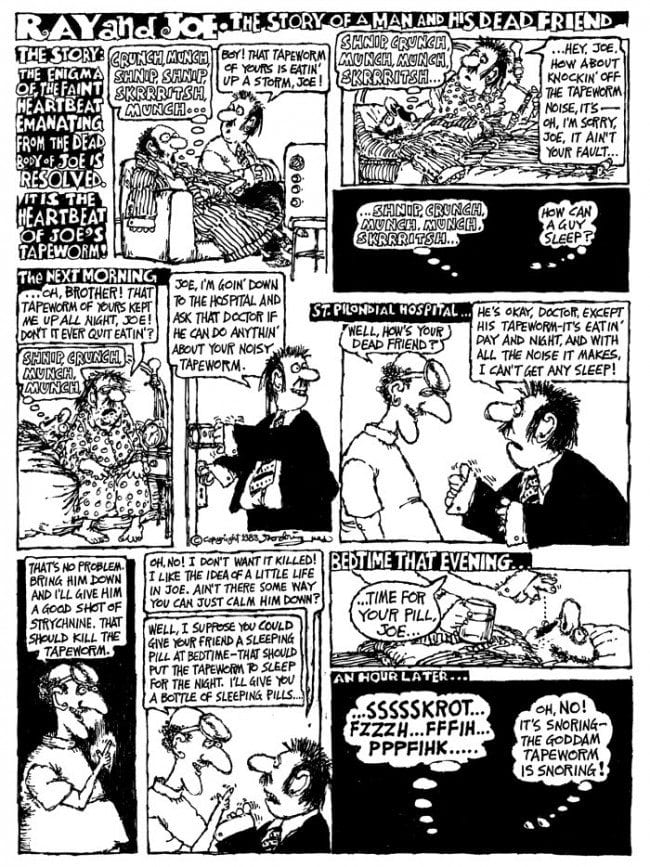

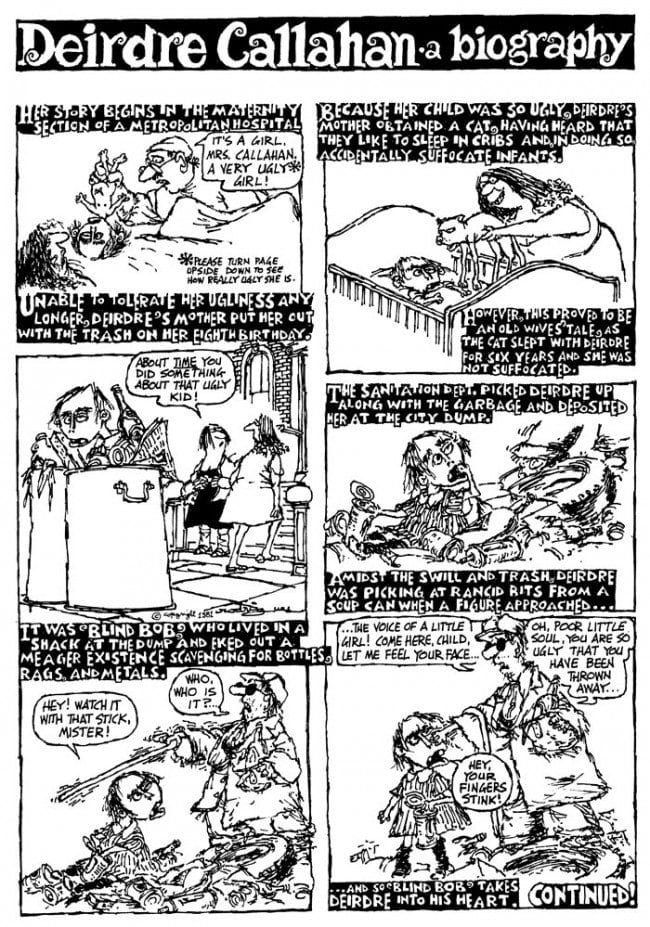

Ray and Joe: The Story of a Man and His Dead Friend, edited by Bob Fingerman and Gary Groth, is a 184-page collection of Rodrigues’s most scabrous work, all of which seemingly ran in the “Lampoon” between 1978 and 1989. I say “seemingly” because the book omits any delineation of which appeared when as though to keep all statutes of limitations on the table as potential defenses against any group libel claims from the tissue-skinned.

The volume contains four narrative pieces, 20 to 84 episodes in length, and several more abbreviated efforts. (A collection of Rodrigues’s gag cartoons is slated for future release.) They seemingly – there’s that word again – appeared, one installment per issue, in primarily nine-panel, single-page strips, with story lines that could shift as abruptly as a dirt track Chevy. The strips do not build to a single, concluding laugh but pull smiles and chuckles at disparate points en route. Rodgrigues works like a silent film comedian, choosing a situation and wringing as many laughs as he can from it before moving on, like Charlie Chaplin starving in a cabin or Harold Lloyd climbing a building, though Rodrigues’s situations are more likely to produce an uplifted eyebrow or sharply sucked in breath: rooming with a corpse; a private detective in an iron lung; the ugliest little girl in the world.

Visually, Rodrigues takes a more-is-more approach. Fingerman, in his introduction, notes that while the work appears “hasty, chicken-scratched and impulsive,” it is actually the product of “a painstaking perfectionist.” Developing individual panels through as many as ten drafts, Rodrigues constructed pages of “masterful” architecture. Solid black patches weigh against vacant white spaces. Some panels are constrained by solid lines; others float free of any. When there are borders, word balloons often bulge beyond them. The panels warp into different shapes and sizes. The typography runs riot. It swells and shrinks, bobs and weaves, mutates into cursive from print.

The chaos does not cause Rodrigues to overlook detail. He enriches characters through choice of hat or style of undershorts. He cast them with Fellini-esq pot bellies or chicken necks. A cornucopia of big noses adorn his clods, buffoons and creeps. And he is a wizard with eyes. On one-page, these dots-within-ovals, with the slightest of fluctuations, may transform a single character from happy to playful to angry to really angry to CRAZY angry to remorseful.

But the key to Rodrigues’s art is language.

In a 2011 Comics Journal interview, S. Gross, Rodrigues’s co-“Lampoon”-ist declared “The highest form of cartooning has no caption.” This is a belief I doubt Rodrigues shared. (Double-checking my suspicion in the only Lampoon anthology I own, “Cartoons Even We Wouldn’t Dare to Print,” I find that only three of Rodrigues’s 11 cartoons there are captionless, a smaller percentage than that of any other frequently represented cartoonist.)

Not only does Rodrigues rely on language for his humor, his use is dazzlingly varied. There are puns, usually so bad as to be extra-delightful. There is medical-sounding double-talk, referencing such conditions as a “cantilevered Jensen’s oracle” and the “ante-bellum cranial sphincter.”. Characters lapse into speaking Spanish or Latin, or are suddenly stricken with a hare-lip. There are out-of-left-field references to Jimmy Hatlo and William Kunstler. Allusions to the work of D.H. Lawrence, Groucho Marx and Humphrey Bogart occur. Digs are delivered at other “Lampoon” cartoonists. A character portrayed as a Negro declares himself a “White Russian,” while white characters are named “Black” and black ones “White” or “Blanche.” One character’s word balloon references a “cheque,” leading another to mock his pretentiousness. Another mentions “Carl Marx” and is laughed at for not knowing the correct name is “Karl.” One running gag is built upon different characters referring to the identical vehicle, a cart, in a variety of less than commonplace ways, “carouche,” “barouche,” and “quadrigue” among them.

Rodrigues’s humor at its most untethered sends him into wacky, wonderful send-ups of and trespasses against his medium’s conventions. He concocts mock letter pages and fan club notes. His captions dispute assertions of his characters’ balloons. A footnote wonders “What the hell is that/” When the “Ugliest Little Girl” becomes even further disfigured, her appearances are blacked-out by a box entitled “Too Hideous For Publication.” Rodrigues will apologize mid-strip for its “inconsistencies” or “verbosity.” He will interrupt a story mid-page, due to its “deteriorating quality,” and begin another one. He concludes one episode by drawing himself into a panel, shooting characters he has tired of – and threatening those in a rival Lampoon strip.

Though the sexual content of his work was muted and the political non-existent, there were few other eyes into which Rodrigues would not stick his thumb. These free-flowing affronts to good taste likely called him to Henry Beard’s attention. But poop and pee only carry one so far. While the customary “no-no”s remained basic to Rodrigues’s conversation, the freedom from constraint they evidenced allowed his creative entry into even more significant areas of creative liberation. His play between word and image and dada-ist assault on form that resulted strike me as Rodrigues’s more notable accomplishment. S. Gross may grumble, but Rene Magritte would, I imagine, smile.