If asked to come up with a reason why 1977 was an important year for British comics, I’d first likely jump to the fact that 2000AD was launched that February. But it also happened to be the first year that cult comix artist Savage Pencil made his wild and volatile pen known to the public, as Rated SavX joyously sets out to remind the comics loving public. Skratchbook is a retrospective compilation-slash-celebration of his 43+ year career, and is an admirable effort to more firmly cement his name into the British canon.

Growing up on a diet of the imported and British comics that made their way onto the racks of his father’s newsagent, Pencil (real name Edwin Pouncey) has made his infamy with his eye catching brand of scratchy, frenetic, cock obsessed and violent (mostly) black and white art inspired by Robert Crumb and Gary Panter. Ever the provocateur, on more than one occasion his work was literally destroyed by some authority figure - including, in one instance, British customs agents - for being “obscene”.

Pencil’s career was made possible thanks to the fracture and explosion that punk made in British culture in the mid 1970s. British punk localized various forms of American culture for a UK audience. It accentuated the more rugged and raw aesthetics of punk music that was so incongruous with the overly polite and mild mannered mainstream, traits can be said to still define England today. Pencil has been closely connected to the music scene ever since. Various strips with Pencil’s “SavX” signature have appeared in music magazines in the proceeding decades since he began drawing, and he was also in a relatively well remembered punk band of his own, as well as being commissioned for various posters and album art projects. Skratchbook is as much a graphic memoir about alternative rock in the UK - and its aesthetics - from the ‘70s to the early ‘90s as much as it is about comics.

Skratchbook collects various examples of Pencil’s work from over the years and presents them in a more or less chronological order, although each chapter is themed rather than dated. The themes range from Pencil’s various comix publications, to specific characters and music trends. The “Black Metal” section features an article by Pouncey himself, in which he demonstrates his obvious passion for and knowledge of the genre. It also comes alongside some of the best illustrations in the book. Here and in the white-on-black “Worship This” chapter, Pencil’s draughtsmanship becomes more steady and controlled than usual. His lines are weightier, but the sense that his figures and designs are coming from some uncontrollable unconscious place is still apparent.

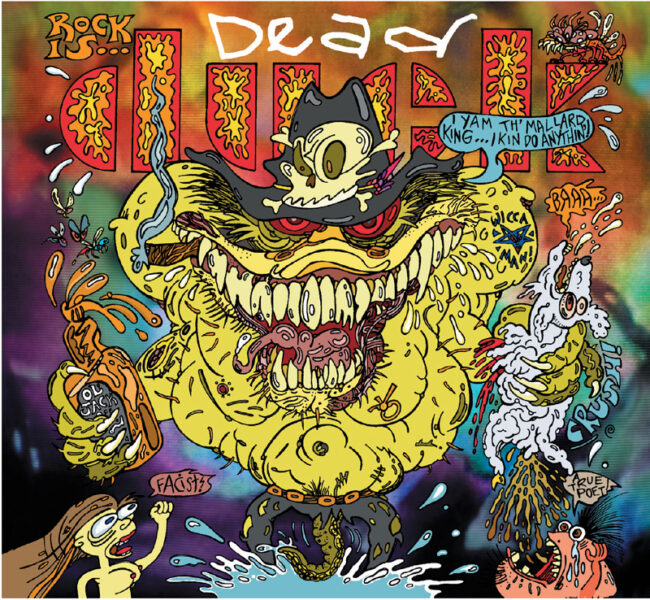

The notion and application of the unconscious is crucial to Pencil’s method. As he says in the introductory Q&A, conducted by Timothy d’Arch Smith, about his process: “It’s automatic drawing, really, using this trippy, improvisational technique that I am slowly perfecting.” One especially feels what he’s talking about in the strips Wolfink and Dead Duck. These set out to be stories that skewer popular culture, but I spend most of the time trying to figure out where lines start and end. On Pencil’s page, the often very detailed art seems to be built out of some jigsaw formation of lines, or appear as if they’re accidental formations.

It’s still pretty crazy to see how fascist symbols - especially the swastika - were adopted and co-opted by the punks. It makes various appearances in Pencil’s work. As the artist says in the opening interview, this was done both to shock the average parent and also to make fun of and confuse the white nationalists who were so keen on using that symbol at the time. As a contemporary reader, whose world includes an event as unexpected as a stoned frog being adopted as an alt right hate symbol, seeing an explicitly far right symbol in a comic can seem both startling and sort of silly. The late ‘70s and 1980s was a time where, generally speaking, things meant what they meant. We hadn’t yet reached the apex of political misdirection that was ushered in in full thanks to New Labour’s spin doctoring. The result of that shift, today’s meme-filled ecosystem, is so reflexive, iconoclastic, and ironic that the swastika appears now to be both too simple and too obvious.

I should be clear that I in no way want to put Pencil in line with any of this lot - his band played the Rock Against Racism tour, and in his interview he is vocally anti-fascist. It is interesting, however, to note how the effect and power of certain symbols change in such a relatively short amount of time, and how the relationship between political hate groups and cartoonists has become a little more complicated in the intervening years. It would be hard to enact such an explicit détournement in a zine today, at a time when what a particular image means isn’t so clear. The meaning is not in the image, it is in the reader, and that makes it hard to imagine such intertextual trolling as appears in Pencil’s work being done effectively in a more contemporary strip.

Flicking through Skratchbook, it’s immediately obvious just how much influence Pencil has had (consciously or not) on today’s punk-inflected, European comix scene. (My mind flicks to the various Instagram illustrators who make their money being tattooists, who draw from the pagan goth/metal influences and punk’s scratchiness.) The press clippings of reviews of Pencil’s work from the time, mostly from the music press, are a nice addition. The inclusion of old reviews in retrospectives is a nice idea in general; with them the reader gets a sense about how discourse has changed, even if the art remains the same. Considering how “new” this all must have seemed at the time, it’s funny to think of the continuation of this style as being a form of nostalgia: nostalgia for a moment that was dominated by an attitude that was archly anti-nostalgic.

This collection’s format amplifies this irony also. Pencil remarks numerous times how his comix work was always limited to the few sheets of paper already in the photocopier’s input tray. Now it’s on nice glossy paper, properly paginated, and comes with an official index and footnotes. I’d want the same if I were in Pencil’s position, it’s just a shame to not be able to interact with the work on flimsy newspaper print as it seems to have been intended.

Skratchbook’s existence makes the case for Pencil’s indoctrination into the history books of British comics and alternative music. This is the comix scene, now with some institutional leverage, making the case that this wasn’t the raving drawings of someone who couldn’t make “real” art, as his detractors no doubt claimed, this was always art, and we knew it.