The aptly titled, still momentous Big Questions saw Anders Nilsen meditating on grand humanist themes of love, faith, death—material that in any other comic would induce the walling of eyes and exasperated sighs. Wisely, the artist smuggled his sincerity into this work in the guise of credulous little birds who think and speak and act like humans. The conceit works wonders: Nilsen can take on those big questions of human existence with an uncommon, un-ironic directness, thanks to his wrenching them out of a human framework entirely. The feat was not unlike Schulz’s, in Peanuts, but rather than the mouth of babes, it’s from the mouth of birds that human sentiments of joy or sorrow, strife or calm, get articulated and argued about. In Big Questions, Nilsen deals with matters of vital human significance, but among a cast of characters well beneath the notice of humans. So novel and strange is that bird's-eye-view that even the most timeworn pontificating gets recast as fresh and alive.

To be curious about human life, but to abjure human actors: Nilsen revisits this technique in his latest book, Rage of Poseidon. Rather than birds, however, this time out the artist uses mythic figures to inquire into the peculiarities of human behavior. Nilsen culls his cast of characters from Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian traditions, but he endows these deities and patriarchs with all-too-human failings, and thrusts them into the contemporary world. So in these stories, Poseidon rages, God sulks, and Athena goes on a bender, while Jesus drives a pick-up and Bacchus holds court in Vegas. Where Nilsen’s birds were trivial creatures with weighty concerns, his gods are ponderous beings with trifling cares.

Of course, the gods have always behaved like humans, petulant and whimsical, with grudges to nurse and desires to slake. So to treat them as human, as messy and conflicted—a vengeful Poseidon, an adulterous Aphrodite, a smelly and distressed God smearing snot across his face—bears little iconoclastic charge. And in positing these figures as our contemporaries, Nilsen often simply juxtaposes their larger-than-life stature with the frivolity of modern existence, so that ancient ambrosia compares favorably with iced lattes, while the Biblical Isaac prefers first-person shooters to his dad’s devout worship. The result is a too-easy cleverness that borders on kitsch, a re-imagining of these characters that merely skims a surface plumbed in greater depth by Robert Coover and John Barth some generations back.

But if Nilsen’s stories end up rather winking at readers than revealing anything to them, the images he conjures to illustrate these parables retain a kind of stately mystery. The tales themselves get told in blocks of text at the bottom of each page—prose that strains to achieve an exotic perspective through tricks like calling a straw “the thin plastic tube protruding from your cup”—but the single-page, black and white images that hover over these captions are often so imposing as to eclipse them entirely. (These stories have seen other incarnations as narrated slideshows, or on gallery walls, where the visuals must be even more imperious. The time-bound physicality of those experiences translates pretty well to the ceaseless, fatalistic way the images unfurl here—across one long scroll of paper, folded accordion-style into discrete pages.) Rarely more than silhouettes, or negative white space pricked out against black backgrounds, Nilsen’s uncanny depictions of a table strewn with bottles, or a suburban landscape drowned in fathoms of inky water, manage to pull off what his prose falls short of. They render the everyday shocking and odd, endowing it with a crisp and vivid unfamiliarity.

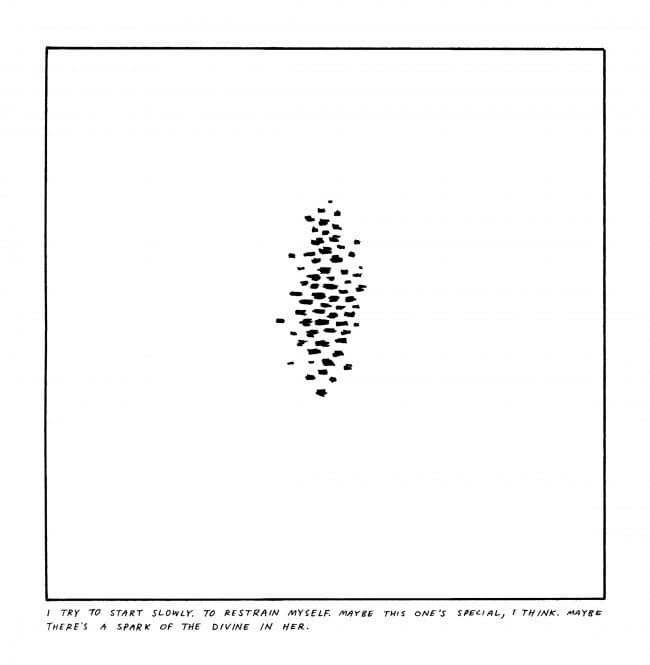

Silhouette images in general waver between the representational and the abstract, between the world we see and one we must invent. So their use in this book, which depicts both the world of the gods and our own sublunary realm, and which trades especially in those legends where gods and men mingle, is an effective one. Nilsen’s lumpy and tousle-haired God, his shadow centered awkwardly against a stark field of white, says more about the humanity of our myths than does any prosaic description of his snot-smearing. Likewise, the centuries that telescope together for Athena are more disarming when they appear as pages of hypnotic, repetitive Op-Art patterns, than when they are described as waves of historical events, and Leda’s experience of the divine, though it’s not a patch on Yeats’s poem verbally, registers visually as arresting and unexpected: simply a stark black column of flame.

It’s in Leda’s and Athena’s tales, too, where Nilsen most succeeds at quickening his godly, empty figures with a sense of life. “Leda and the Swan” is brief and oblique, the most abstract piece in the volume and one of its shortest, while “The Girl and the Lions” is the longest and most conventional, an account of Athena waking hung-over in mysterious circumstances, haunted by the memory of an early Christian martyr. These stories stand out not just because their imagery is so striking—a cop car’s siren and windshield glowing in the night, a fridge or a gun drawn in contour lines after an entire book of simple silhouettes—but because their characters seem legitimately confused about what the hell we humans do. Zeus’s love for the mortal woman is met with a defiance that this king of the gods fails to understand, and Athena, the goddess of wisdom, remains perplexed for centuries that there can exist such a thing as blind, impossible faith. There is no cuteness here about video games or drinking straws, no safe distance from the “pathetic and loathsome” hordes of humanity that Poseidon merely observes at first, then rages against. In these two stories, especially, Nilsen is back to asking those fundamental questions again, and they show that this artist is at his best when he’s also genuinely, profoundly at a loss.

It’s in Leda’s and Athena’s tales, too, where Nilsen most succeeds at quickening his godly, empty figures with a sense of life. “Leda and the Swan” is brief and oblique, the most abstract piece in the volume and one of its shortest, while “The Girl and the Lions” is the longest and most conventional, an account of Athena waking hung-over in mysterious circumstances, haunted by the memory of an early Christian martyr. These stories stand out not just because their imagery is so striking—a cop car’s siren and windshield glowing in the night, a fridge or a gun drawn in contour lines after an entire book of simple silhouettes—but because their characters seem legitimately confused about what the hell we humans do. Zeus’s love for the mortal woman is met with a defiance that this king of the gods fails to understand, and Athena, the goddess of wisdom, remains perplexed for centuries that there can exist such a thing as blind, impossible faith. There is no cuteness here about video games or drinking straws, no safe distance from the “pathetic and loathsome” hordes of humanity that Poseidon merely observes at first, then rages against. In these two stories, especially, Nilsen is back to asking those fundamental questions again, and they show that this artist is at his best when he’s also genuinely, profoundly at a loss.