I’ve never felt much fondness for a particular strain of critically celebrated confessional comics that emphasizes the trials, tribulations, and neuroses -- with particular emphasis placed on the sexual dysfunctions -- of schlubby men. If I considered it part of my education to read comics grandfathers like Crumb and Pekar I also resented the process because I found so little in their work to respond to. Their insecurities seemed passe,’ remarkable only for their all-consuming intensity; their voices struck me as shrill, offensive and repulsive not because they were trumpeting truths middle-America found too uncomfortable to confront but because they were desperate for any attention. Only their art -- expressively whacked out and gonzo at the best of times in Crumb, hard-bitten and uncompromisingly ugly at the best of times in Pekar's collaborations -- struck me as worthy of attention. If that was all they had, though, it was at least more than their successors found to offer: Joe Matt, Chester Brown, Dennis Eichhorn and all the rest of a particular cohort that came of prominence in the 90s were so monomaniacally fixated on their sexual and romantic frustrations that it was as if they had little effort left to spare for their art. Their work was every bit as grotesque as the comics of their predecessors, yes, but lacked for spark or originality: it was disgust for world and disgust for self absent all charm, all wit, all the care that at least allowed Crumb and Pekar’s stories to play as earned observation and not as loathsome self-pity. The art itself was the perfect metaphor for the genre’s degradation, a chart demonstrating in real time the correlation between paucity of thought and paucity of form. By the release of David Heatley My Brain is Hanging Upside Down in 2008 the chart seemed to bottom out: here was an artist of no great talent -- some competence, yes, as evidenced by the book’s intricate cover and other choice paintings scattered throughout, but marred by a deliberate resort to a style of naive scribbling that did his shallow observations no favors -- possessed of a bundle of experiences and prejudices and desires so dull that they made the concerns and observations of the 90s coterie seem the stuff of Proust or Nabokov.

Qualification, Heatley’s first full-length adult work in over a decade, seems nominally more exciting than Brain. It, at least, has the kind of narrative hook that Brain made sure to eschew: haunted by a traumatic childhood that found his sexually abusive father and negligent, competitive mother pushing him towards the 12-Steps programs they themselves relied on and harried by the stresses of an adulthood and marriage he feels ill-equipped to handle, he turns first to Debtor’s Anonymous and then to Alcoholics-Anonymous, Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, and a slew of other programs that offer him community as well as a marked sense of spiritual fulfillment. Along the way he recounts not just his own difficulties as a husband, a father, and a struggling cartoonist but his encounters with a bevvy of characters from his time in the programs; if this parading of hard-cases feels exploitative (as Heatley’s callous treatment of them suggests it is; he’s quick to shuttle them in to provide a piquant anecdote or telling example before shuffling them out, never to be seen or discussed again) it at least lends Heatley’s own petty, carping concerns a sense of pathos: whenever the pace is notably lagging or whenever the shallowness of Heatley’s own problems become apparent it’s easy enough for him to trot out and hide behind one more of his anonymous peers. Their inclusion is ostensibly (according to Heatley’s own introduction) an effort to “highlight the universality of their personal struggles,” to “provide examples of how to live…(and) serve as cautionary tales,” but like all of Heatley’s confessions and explanations it’s ultimately only ostensible, a diversion he can throw up any time he comes too close to confronting the truth of his situation: that his concerns are the stuff of cheap narcissism, his fears are mundane, and his ability to shape them both into art subpar.

My disdain for Heatley’s breed of self-effacing memoir doesn’t arise from some knee-jerk dismissal of the genre, from some crank belief that there is nothing to be mined from inward looking stories or that their prominence presages some apocalyptic shift in artistic sensibility towards naval gazing so all consuming it will bring the culture curling in on itself. I readily admit to a fondness for Why?-frontman Yoni Wolf’s patented brand of self-inflicted humiliation, consider Marie Calloway’s memoir What Purpose Did I Serve in Your Life and Karl Ove Knausgaard’s multi-volume My Struggle two of the most significant artistic works of the last decade. But in these exemplary cases the artists’ obsession with their failures and disgust with themselves isn’t the subject so much as it is a springboard to deeper aesthetic pleasures and haunting revelation: Yoni’s songs aren’t only a poetic delight, all nested rhymes and intricately structured lyrics studded with metaphors that seem improbable at first but inevitable in hindsight; they are also unsparingly funny and deeply sad investigations of an ego that has devoured itself for sustenance and in doing so been left alone in a closed-loop that leaves no room for escape besides death. The concerns of Knausgaard’s memoirs may not be so far removed from Heatley’s own -- attempts to cope with abusive parents and traumatic childhoods, to reconcile the conflict between one’s ambitions as an artist and one’s obligation to children and a spouse who feel increasingly burdensome -- but they are elevated by an exacting eye, a stylistic genius and a preoccupation with deeper questions that endow even the most mundane observations with pathos. Knausgaard is a lout, yes, but he’s a lout driven by philosophical concerns that allow him no easy out and transform his neurosis into a laser-honed scalpel; his interior monologue is constantly dithering, contradicting itself, running up against and investigating the veracity of its own judgments and assumptions about his society, his peers, his self in its unflagging commitment to truth. Calloway’s confessional is similarly focused on this process of interrogation; while it may be best remembered now for its salacious details it better deserves study as a dead-pan-disturbing investigation of how our attempts to arbitrate between the desires of others and ourselves in a world that sees us all as branded product existing only to fulfill said desires leads inevitability to a kind of self-abnegation posing as self-creation. As the poet Rachel White has it, “(What Purpose Did I Serve in Your Life?)” is…a book that grapples with interior…creates an interior,” a task all the best confessional writing strives towards. Whatever their faults one could never argue that Crumb and Pekar or their many imitators were not at least working in some way to make sense out of and so shape their own understanding of their respective identities; their expressive stylings and willingness to make caricatures of themselves would immediately put pay to that misapprehension.

My disdain for Heatley’s breed of self-effacing memoir doesn’t arise from some knee-jerk dismissal of the genre, from some crank belief that there is nothing to be mined from inward looking stories or that their prominence presages some apocalyptic shift in artistic sensibility towards naval gazing so all consuming it will bring the culture curling in on itself. I readily admit to a fondness for Why?-frontman Yoni Wolf’s patented brand of self-inflicted humiliation, consider Marie Calloway’s memoir What Purpose Did I Serve in Your Life and Karl Ove Knausgaard’s multi-volume My Struggle two of the most significant artistic works of the last decade. But in these exemplary cases the artists’ obsession with their failures and disgust with themselves isn’t the subject so much as it is a springboard to deeper aesthetic pleasures and haunting revelation: Yoni’s songs aren’t only a poetic delight, all nested rhymes and intricately structured lyrics studded with metaphors that seem improbable at first but inevitable in hindsight; they are also unsparingly funny and deeply sad investigations of an ego that has devoured itself for sustenance and in doing so been left alone in a closed-loop that leaves no room for escape besides death. The concerns of Knausgaard’s memoirs may not be so far removed from Heatley’s own -- attempts to cope with abusive parents and traumatic childhoods, to reconcile the conflict between one’s ambitions as an artist and one’s obligation to children and a spouse who feel increasingly burdensome -- but they are elevated by an exacting eye, a stylistic genius and a preoccupation with deeper questions that endow even the most mundane observations with pathos. Knausgaard is a lout, yes, but he’s a lout driven by philosophical concerns that allow him no easy out and transform his neurosis into a laser-honed scalpel; his interior monologue is constantly dithering, contradicting itself, running up against and investigating the veracity of its own judgments and assumptions about his society, his peers, his self in its unflagging commitment to truth. Calloway’s confessional is similarly focused on this process of interrogation; while it may be best remembered now for its salacious details it better deserves study as a dead-pan-disturbing investigation of how our attempts to arbitrate between the desires of others and ourselves in a world that sees us all as branded product existing only to fulfill said desires leads inevitability to a kind of self-abnegation posing as self-creation. As the poet Rachel White has it, “(What Purpose Did I Serve in Your Life?)” is…a book that grapples with interior…creates an interior,” a task all the best confessional writing strives towards. Whatever their faults one could never argue that Crumb and Pekar or their many imitators were not at least working in some way to make sense out of and so shape their own understanding of their respective identities; their expressive stylings and willingness to make caricatures of themselves would immediately put pay to that misapprehension.

Heatley, by contrast, roundly rejects engaging with interior in any meaningful way, a fact apparent before all else in his own self-depiction. As Chris Ware had it in personal correspondence with Heatley, he is one of the “few autobiographical cartoonists who doesn’t…make (himself) into a shticky Woody Allen/Joe Matt kind of character,” an observation Heatley is quick to agree with. “Somehow there’s just a blankness to the ‘me’ in those stories,” he offers, but there’s neither accident in Heatley’s authorial minimization nor humility: it’s all part of an elaborate artistic con job. Rather than minimize his place in the story, this “blankness” is intended to elevate it. Yes, by reducing himself to a forgettable cartoonish abstraction so generic it almost defies description he is better able to emphasize the universality of his emotions, to make it all the easier for readers to place themselves into his shoes. Yet by playing out the story entirely in his own internal voice while presenting himself as some kind of cipher he is not only asking audiences to accept that these feelings are universal, he is then asking them to accept that these universal feelings are somehow also the particular results of his peculiar circumstances. It’s a subtle shift that leaves readers thinking of his individual concerns as of universal importance. In case there was any missing the point, it’s difficult not to notice how his emotions are always presented with the utmost urgency: just witness his soulful doe eyes, always on the verge of tearing up when they aren’t wide in earnest astonishment and fellow-feeling. Pay attention to the way his beatific, self-satisfied smiles fill the page whenever he is on the verge of spiritual revelation or his anguished frowns when confronted with the difficulties of the world blow up to fill panel upon panel. Heatley never feels things by half and cannot let readers ignore this. He could argue that he works in this way to parody himself and his emotions, but no character besides his wife, Rebecca, is afforded a similar capacity for self-expression. Instead they’re saddled with caricatures so specific and so exaggerated they’re reduced to a single defining trait: a pair of bug-wide eyes, a set of too-pearly, too-big teeth or manic thousand-yard stares and grotesque facial contortions.

Heatley, by contrast, roundly rejects engaging with interior in any meaningful way, a fact apparent before all else in his own self-depiction. As Chris Ware had it in personal correspondence with Heatley, he is one of the “few autobiographical cartoonists who doesn’t…make (himself) into a shticky Woody Allen/Joe Matt kind of character,” an observation Heatley is quick to agree with. “Somehow there’s just a blankness to the ‘me’ in those stories,” he offers, but there’s neither accident in Heatley’s authorial minimization nor humility: it’s all part of an elaborate artistic con job. Rather than minimize his place in the story, this “blankness” is intended to elevate it. Yes, by reducing himself to a forgettable cartoonish abstraction so generic it almost defies description he is better able to emphasize the universality of his emotions, to make it all the easier for readers to place themselves into his shoes. Yet by playing out the story entirely in his own internal voice while presenting himself as some kind of cipher he is not only asking audiences to accept that these feelings are universal, he is then asking them to accept that these universal feelings are somehow also the particular results of his peculiar circumstances. It’s a subtle shift that leaves readers thinking of his individual concerns as of universal importance. In case there was any missing the point, it’s difficult not to notice how his emotions are always presented with the utmost urgency: just witness his soulful doe eyes, always on the verge of tearing up when they aren’t wide in earnest astonishment and fellow-feeling. Pay attention to the way his beatific, self-satisfied smiles fill the page whenever he is on the verge of spiritual revelation or his anguished frowns when confronted with the difficulties of the world blow up to fill panel upon panel. Heatley never feels things by half and cannot let readers ignore this. He could argue that he works in this way to parody himself and his emotions, but no character besides his wife, Rebecca, is afforded a similar capacity for self-expression. Instead they’re saddled with caricatures so specific and so exaggerated they’re reduced to a single defining trait: a pair of bug-wide eyes, a set of too-pearly, too-big teeth or manic thousand-yard stares and grotesque facial contortions.

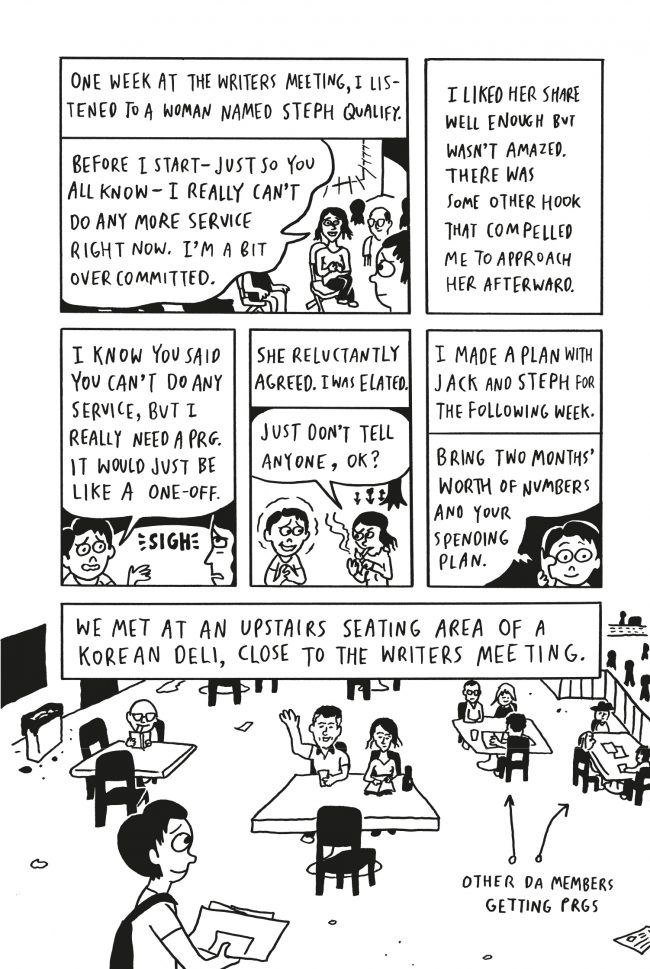

It is not a problem confined to the art, either, but one that crops up in the narrative and its structure.Qualification must be 70% text by volume, page after page filled to every edge with narrations and dialogue that often leave the art feeling ancillary. One could contend that such a formal decision is necessary in a book built around an author’s self-reflection, that Heatley’s self-obsessed monologues are his attempts to create an interior, but it’s a dodge. For despite all the energy Heatley spends cluttering his book with text he does remarkably little honest self-reflection. It’s not that the author is bad about identifying the emotions he was feeling at the time or explaining them; the book is all explanation, box after box after box after box cataloging his every shame, disappointment, frustration or fear. The problem is that these feelings are only ever given explanations so superficial they cannot confront the underlying causes for the worst of Heatley’s behavior. He lucks into an astoundingly well-paid part-time job that he resents and sabotages out of discontent he can’t be bothered to explain. He spends page after page admitting to masturbatory fantasies for co-workers, for friends, for fans, for what seems every stranger on the street and yet never bothers to investigate why he has these obsessions, opting instead to feel disgust for himself; when he considers cheating on his wife (and eventually does) he excuses it as “barely sexual…I felt a desperate, compulsive need to be a ‘safe’ guy for women to trust.” Later, when confronting his attraction to a fellow Anonymous member, he again dissembles: “I liked her share well enough but wasn’t amazed. There was some other hook that compelled me to approach her afterward.” It’s as if he’s suddenly forgotten how he spent two-hundred pages harping on about how his uncontrollable libido drags him towards every woman he sees, or that he thinks the audience is so inattentive they’ll believe this lame equivocation. Each time he’s forced to confront the obvious truth of his situation, to admit any kind of wrongdoing or deep flaw he finds a new way to rationalize it when not avoiding it altogether.

He spends little more time plumbing the importance of the thousand episodes he chose to fill the book. An encounter with one SLA attendant who asks him to “be (his) daddy,” a would-be sponsor of his who simply stops returning his calls, an “action group” that implodes after a single meeting: all of these and a dozen more anecdotes come to nothing, reveal nothing, establish nothing of mood or tone or truth beyond the fact that 12-Step programs draw in damaged people. Nor is anything made of the these damaged people. Heatley loves to parade them out and provide a single detail or two on their personalities but aside from the most important of supporting cast members, all disappear from the story almost as soon as they are introduced. Heatley talks in the introduction about “highlighting the universality of their personal struggles” but then spends so little time investigating who they are, how they came to be this way and how they live that it’s impossible to see them as anything beyond caricatures; most show up in a single image, afforded only a single caption to explain some salient character trait. If his interest is with their “personal struggles” then why does he not allow them a chance to reveal something personal? If they’re meant to serve as “cautionary tales” then why are we only permitted such a narrow glimpse of their lives that they almost exclusively end up looking like freaks?

For a work supposedly about confronting the ugliest elements of oneself and jettisoning the illusions placed on us by our traumas, by our self-illusions, by spiritually manipulative institutions -- be they religion or 12-Step programs (a link that Heatley draws again and again; it’s no accident that his parents substituted the community of Church they once had for the community provided by Anonymous programs or that Heatley himself describes the particular positive energy he feels after each meeting as a “God burst”) -- it’s revealing that even to its very last pages Qualification opts to avoid the real work of self-confrontation. For what finally frees Heatley from the pernicious influence of these illusions and institutions is not a development arrived at after years of honest interrogation, of fearless self-assessment nor any relationship that reveals to him the depths of his selfishness but a throw-away line from his therapist. “That’s a powerful illusion you’re operating under, [David]. But that’s all it is. An illusion,” he’s told, and with that simple observation is freed from his addiction not only to 12-Step programs but to the trauma’s that pushed him towards the organizations in the first place. In the final twenty pages that follow this epiphany Heatley finds it in him to forgive his father, to come to an understanding with his mother, and to heal a marriage on the edge of divorce; conflicts that were once so powerful they left him barely able to talk to the other party, that have haunted the book for three-hundred pages, are wrapped up so nice and tidy they’re even granted a bow of an ending that assures readers how Heatley and Rebecca’s love for each other, “as imperfect as it may be, still works.” There’s no sense of pace to these resolutions; it’s as if Heatley knew the end of the book was upon him and figured the audience would simply have to accept this explanation because how could they disprove his experience. But it’s not that I doubt the veracity of these feelings Heatley has: if he’s never been honest about what underlies his emotions he’s always at least been honest about what those emotions are. No, what seems doubtful is that these primal scars would scab over with one simple bit of advice, that all the strife that has defined his life could be so neatly brushed aside; it feels instead as if it’s been swept under the rug. Heatley may think that he’s escaped his addiction to the easy answers and illusory sense of well-being that characterize his experience of 12-Step Programs, but what is this miraculous, life changing burst of insight from his therapist (presented in a single page spread that frames the experience as something transcendental and grand) if not another religious epiphany of the exact same kind he’s claimed to have outgrown? What is this ending, so convenient it, if not one more in the endless series of dodges that have characterized Qualification and, if Heatley is to be believed, his own life story?

For a work supposedly about confronting the ugliest elements of oneself and jettisoning the illusions placed on us by our traumas, by our self-illusions, by spiritually manipulative institutions -- be they religion or 12-Step programs (a link that Heatley draws again and again; it’s no accident that his parents substituted the community of Church they once had for the community provided by Anonymous programs or that Heatley himself describes the particular positive energy he feels after each meeting as a “God burst”) -- it’s revealing that even to its very last pages Qualification opts to avoid the real work of self-confrontation. For what finally frees Heatley from the pernicious influence of these illusions and institutions is not a development arrived at after years of honest interrogation, of fearless self-assessment nor any relationship that reveals to him the depths of his selfishness but a throw-away line from his therapist. “That’s a powerful illusion you’re operating under, [David]. But that’s all it is. An illusion,” he’s told, and with that simple observation is freed from his addiction not only to 12-Step programs but to the trauma’s that pushed him towards the organizations in the first place. In the final twenty pages that follow this epiphany Heatley finds it in him to forgive his father, to come to an understanding with his mother, and to heal a marriage on the edge of divorce; conflicts that were once so powerful they left him barely able to talk to the other party, that have haunted the book for three-hundred pages, are wrapped up so nice and tidy they’re even granted a bow of an ending that assures readers how Heatley and Rebecca’s love for each other, “as imperfect as it may be, still works.” There’s no sense of pace to these resolutions; it’s as if Heatley knew the end of the book was upon him and figured the audience would simply have to accept this explanation because how could they disprove his experience. But it’s not that I doubt the veracity of these feelings Heatley has: if he’s never been honest about what underlies his emotions he’s always at least been honest about what those emotions are. No, what seems doubtful is that these primal scars would scab over with one simple bit of advice, that all the strife that has defined his life could be so neatly brushed aside; it feels instead as if it’s been swept under the rug. Heatley may think that he’s escaped his addiction to the easy answers and illusory sense of well-being that characterize his experience of 12-Step Programs, but what is this miraculous, life changing burst of insight from his therapist (presented in a single page spread that frames the experience as something transcendental and grand) if not another religious epiphany of the exact same kind he’s claimed to have outgrown? What is this ending, so convenient it, if not one more in the endless series of dodges that have characterized Qualification and, if Heatley is to be believed, his own life story?

Heatley’s great sin isn’t that he is a sinner, a horrible, petty, carping mess of a human dominated by urges and appetites he will hardly account for. It’s that he is a boring sinner who offers neither aesthetic pleasure nor insight only to then demand sympathy for unveiling his wriggling ego. The human race is a mess, each and every one of us; who living in an age this demented could be anything besides? There’s no great shame in admitting to this shortcoming. Conversely, though, there is no great virtue in trumpeting the same, least of all in an age where digital forums have given every last one of us a public line to air our laundry by. But where other more interesting artists have taken up the difficult task of grappling with themselves to arrive at a more full sense of identity, to explore questions of consciousness or provide unknown aesthetic pleasures, Heatley has chosen to do little besides prey on his readers’ sympathies. It’s as if he’s saying “The fact that I can acknowledge what a rotten bastard I am is actually proof that I am NOT a bastard. If anything it proves I have the capacity for great goodness,” while simultaneously asking us to absolve him of his transgressions because of an 11th-hour conversion to a less selfish way of being. That he treats every other character in his story with barely-disguised contempt, that he tries to pull one over on his readers and refuses to own up to his own worst instincts can’t disguise this, though: for all of Heatley’s quibbling to the contrary Qualification ends up nothing but another plea for attention from an inveterate narcissist.

Heatley’s great sin isn’t that he is a sinner, a horrible, petty, carping mess of a human dominated by urges and appetites he will hardly account for. It’s that he is a boring sinner who offers neither aesthetic pleasure nor insight only to then demand sympathy for unveiling his wriggling ego. The human race is a mess, each and every one of us; who living in an age this demented could be anything besides? There’s no great shame in admitting to this shortcoming. Conversely, though, there is no great virtue in trumpeting the same, least of all in an age where digital forums have given every last one of us a public line to air our laundry by. But where other more interesting artists have taken up the difficult task of grappling with themselves to arrive at a more full sense of identity, to explore questions of consciousness or provide unknown aesthetic pleasures, Heatley has chosen to do little besides prey on his readers’ sympathies. It’s as if he’s saying “The fact that I can acknowledge what a rotten bastard I am is actually proof that I am NOT a bastard. If anything it proves I have the capacity for great goodness,” while simultaneously asking us to absolve him of his transgressions because of an 11th-hour conversion to a less selfish way of being. That he treats every other character in his story with barely-disguised contempt, that he tries to pull one over on his readers and refuses to own up to his own worst instincts can’t disguise this, though: for all of Heatley’s quibbling to the contrary Qualification ends up nothing but another plea for attention from an inveterate narcissist.