Technology advances, becomes more affordable, and works it way from its previous perch atop high-rise office buildings down to the consumer population on the ground. Once prohibitively expensive tools proliferate amongst the populace, and eventually reach a point of insidious ubiquity. The very material of the world starts to feel digitized, and those with eyesight damaged by too-frequent staring into screens may feel alienated enough to postulate the mathematical probability that our world could be a computer simulation.

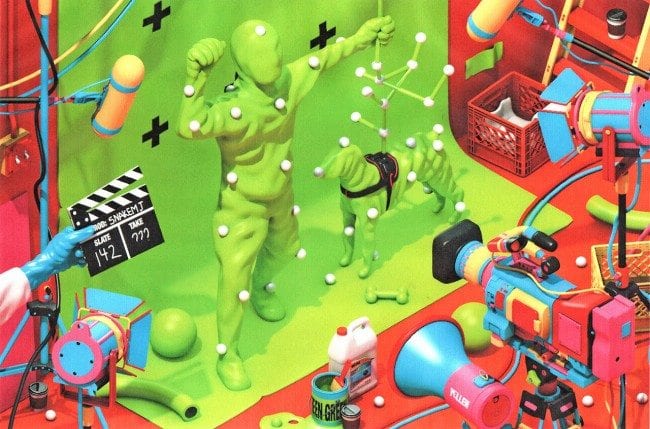

The scale of our entertainment industry changes accordingly, and nowadays it takes a small army to manufacture a blockbuster: Thousands working to render a spectacle of explosions and violence at a scale impressive enough to dwarf a sense of the human, and so satisfy a mass audience's adjusted-for-inflation sense of what is expected for their ticket price. In times like these, one talented person working with diligence can use tools widely available and create work unimaginable at any point prior in human history. Such work feels subversive just by existing in dialogue with the world. While early Pixar shorts were demonstrations of the software they had available to them, designed to seek investors, Jordan Speer is able to work on his own, and use the smooth plasticine surfaces provided by CGI to critique the corporate culture that maintains its power through computer technology, and fills the world with plastic.

These conflicts between individual and corporation make up the material of the world of this book, and Jordan's name on the cover is written in bright orange blood while the title QCHQ functions as its own physical object, a corporate logo fallen from a building to crush a car, with its driver exuding authorial ooze.

The interiors largely retain this angle, offering three-quarters perspective on silent vistas of urban landscapes or office interiors. It is a vantage point familiar to players of Sim City 2000, designed to show off shape. Most pages are single-panel tableaus, displaying the future world and telling the story of its world through objective observation, with some exposition revealed through corporate memos displayed on computer screens. Sometimes the camera pulls back or shifts slightly, to play games with the sense of scale we see, and hint that there is always something greater behind the world we see, something sinister.

The book looks exquisite. The art is beautiful, brightly colored, and feels smooth to the eye, with its primary palette based around the bright orange of the Nickelodeon logo and the pinks and turquoises of fluorescent neon gels. Anyone who has been looking for a heir to Paper Rad's approach to color and settling for Brendan McCarthy comics or Lynn Varley's work in The Dark Knight Strikes Again can breathe a sigh of relief. Here is a step forward that operates on a level of artistic awareness, rather than just playing with various effects filters. Speer's work embraces the aesthetic appeal of gloss but seems aware that "rendering" refers not just to the time it takes a computer to create a viewable form of an effects-laden image, but also to the industrial processing of lard.

Objects are anthropomorphized, and trucks drive around with expressive lidded eyeballs, making them function effectively as characters—and commensurately, every character could be a toy. Contained inside all of them is a goo that seeps out when violence occurs, and that goo itself could be a toy, a slime product, the color of Silly Putty or Gak. It's a post-Singularity vision of a world where everything is for sale. The world of QCHQ is a world that feels, like our own, to be a planet-scale toy set for super-rich man-children. Surveillance cameras are on corners, outfitted with cartoon pupils to humanize the all-seeing eye of the overlord. Meanwhile, the corporation's client is an Egyptian God, appealingly designed to remind the reader of cartoons' and comic books' willingness to utilize longstanding mythology as something merchandisable; but in the context of the story, we are reminded that blood sacrifice is demanded from such figures. The corporation's violent acts are performed in the name of Pentadrox, the Blood Lord.

QCHQ's employees are figures outfitted in rubber gloves and large helmets. Their plastic textures sidestep the uncanny valley, and speak to cartoon conventions, but also signify a sterilized existence. Our main character's gloves resemble Mickey Mouse's, but he does not go on adventures, nor does he work in surgery, in contact with the multi-colored glops glimpsed elsewhere. He works at a computer terminal and receives corporate memos, written in Comic Sans, the dumb, friendly replacement of the human hand.

Speer makes the argument that the friendly cartoon figures we see are product of a world that makes its money off blood and dehumanization. The perspective designed to highlight shape and form of computer-modeling software is employed to say that this is the world, were we to objectively see it. Sound effects, in chalk-like white, lend their own meaning: their otherness from the aesthetic of the visually concrete world implies a separate sense, the way sound itself strikes a different nerve than light. Within the world we see, there are slight signs of revolt, in graffiti on walls, but this itself is pixelated, hashtagged #cybergang, pointing to its falseness, a sense that it's already been appropriated by (and is inextricable from) the world's machinery. The book itself, existing within capitalism, is far from a perfect radical object: It is still printed in China, of course.

Some of the single-page images here function beautifully as the sort of things that travel the web on their own strength, through the social media channels common today. The book framework lends a narrative context, making it feel like something is being explained, that a hidden aspect of the modern world is being revealed, in a way that does not hold when seeing these images on a website that's one among many.

QCHQ feels like an essential guidebook for life in 2014. If we are going to spend as much time on the internet as we are, this sort of book, viewable on paper, away from the computer but still a product of it, feels not like a warning or a satire but a map of the territory we're trapped inside. Comparing it to computer-generated comics from another era feels hilarious in a double-edged way; it's not just that the toolset Speer is working with is far more advanced than what was available in the past, it also that the world we're living in is far weirder than the past's attempts at prognostication would have it. This is all to say that QCHQ puts 1989's Batman: Digital Justice to shame, but it shames far more than that. In the world of modern computing, there are no heroes, not even the artist himself. All are victims, and all are helpless. The book finds joy in its bleak worldview by painting blood in pastel tones and seeing beauty in the material of the small moments and in the sheer majestic grandeur of the world outside our scope.