The stumbling block facing critical discussion of Prince Valiant is that it has probably done more time than any other as the popular imagination’s pick for “greatest comic ever.” Especially given the intelligent cartoonists of the past few decades’ moves away from genre and into the territory of “real literature,” it seems unlikely that a warmly narrated, incrementally plotted comic about knights will ever occupy that place of pride again. When a field develops a critical culture, the work that existed before it tends to meet with unkind fates. The conventional wisdom surrounding Prince Valiant these days characterizes it as a fussily drawn, belabored relic of the past.

Of course, critical judgments of a comic stop mattering once you read it. A few pages into the fourth of Fantagraphics’ beautifully reprinted new editions of Hal Foster’s masterpiece and it’s difficult indeed to remember that this isn’t the greatest comic ever. Comparisons of Foster’s work to that of more recent luminaries like Chris Ware and Jaime Hernandez are apples to oranges; readers will more than likely prefer one to the other, but there’s no convincing way to prove one kind of comic is objectively better than the other. And the mastery Foster brings to bear on his every panel may have been equaled both before and since his prime, but it’s never been surpassed. As far as long-form serialized action comics go, the only equal to Foster American comics have produced is Kirby, and Kirby was never shy about proclaiming his debts to the master.

As an action artist, Foster is surprisingly unique, especially for someone whose influence was once so widely spread. Rare are the “fight scenes” in Prince Valiant. The typical action comic’s focus on individuals engaged in impact-for-impact conflict with one another pops up only sporadically here -- what Foster liked to draw was battle scenes. Time and again massed forces of armed men draw together and clash in tapestrial panels that focus less on the actions of individuals and more on entire military maneuvers, with each figure contributing to the construction of an awe-inspiring whole. Foster’s eye for detail is meticulous and unerring, but the real pleasure of his dense, rich panels is how every detail carries some bit of story information, some actual content to chew on and savor. One suspects that the reason the first- and second-generation superhero artists who built an industry in which swiping Foster panels was a prominent working method didn’t copy this approach along with the faces and figure drawings is that they simply lacked the skill to do so.

Foster’s emphasis on realist detail and construction is so great, in fact, that it pulls his work out of dialogue with the vast majority of comics. Finely honed as his cartooning chops were, Foster engages with the firmly realist values of figurative painting at least as much as the more abstract principles of cartoon drawing. When the thin clear lines that have built up the comic for the previous three volumes give way to larger areas of black space and looser, more frenetic brushwork midway through volume four, it’s as reminiscent of painting’s transition from realism to Impressionism as it is of similar transformations in the work of cartoonists like Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli. Suddenly Foster’s landscapes are no longer beautiful stage sets, but real environments that the figures alternately sink into and emerge from. Whether it’s in a perfectly observed portrait panel, a sweeping natural landscape, or one of the apocalyptic battle tableaux, there is a constant sense that these comics are just as much a milestone in the adaptation of figurative pictorial values to print media as the engravings of Doré or Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers.

It’s this very sense of Prince Valiant as something that can speak to art forms beyond just comics that elevates it above most work done in the medium. Foster is as much an heir to Rembrandt as he is a progenitor to Wally Wood, and Prince Valiant’s freedom from the cinematic-style framing that has completely overrun comics in the past half-century is deeply refreshing. Unlike his contemporaries Milton Caniff, who pulled angles and shot transitions from the movies with aplomb, and Alex Raymond, who relied heavily on photo reference, Foster seems to have understood the fundamental truth of comics as a medium of single drawings placed in proximity to one another. Rather than attempting to hop its panel borders and mimic the continuous motion of film, Prince Valiant ceases its narrative at then end of each panel before building it back up a little bigger with the next. If Caniff’s comics were speaking to film, and Raymond’s to photography, Foster’s dialogue is with narrative painting, in which the space between individual pictures is easy to overlook when faced with the sum of the parts.

The only other artist-in-comics to have his feet so squarely planted in the classical-arts tradition is Frank Frazetta, but in Foster there is very little of Frazetta’s kitsch. Even the breeziest reading of Prince Valiant makes it obvious that Foster saw his characters as living people rather than painted icons. The only thing separating Foster’s nuanced, human characters’ travails from those found in the work currently conceptualized as “intelligent” comics is Prince Valiant’s unabashed presentation of life as fun, not tortuous or paranoid. In Foster the brutal lynching of a murderous priest is not tragedy but a simple expediency (“Val did what had to be done, and with no squeamishness whatever…”), and a rival king’s torturing the title character by binding his digits to a circular frame like some comic-book Vitruvian Man is less an agony than a chance to meditate in anticipation on the sword-swinging vengeance sure to follow. There is bad and good in Prince Valiant, truly dark moments as well as moments of unrestrained and shining happiness, but Foster has no scruples about letting his characters’ sun-dappled enjoyment of life and its adventures win out over their neuroses.

In many ways this outlook is symptomatic of the wider culture during the years Foster drew the comics collected here: it is the nation at war that most often finds heroism in killing and joy in battle. The narration finds a way to justify every one of the many lives taken by the story's heroes (often those of blonde-haired, blue-eyed Saxons in this volume), and occasionally comes close to outright jingoism in doing so. But Foster transcends his times by giving every armed conflict a clear reason to occur—beyond a simple desire to up the comic’s body count. Prince Valiant’s characters may live barbaric lives in barbaric times, but Foster gives their very human emotions just as much time as their swordplay.

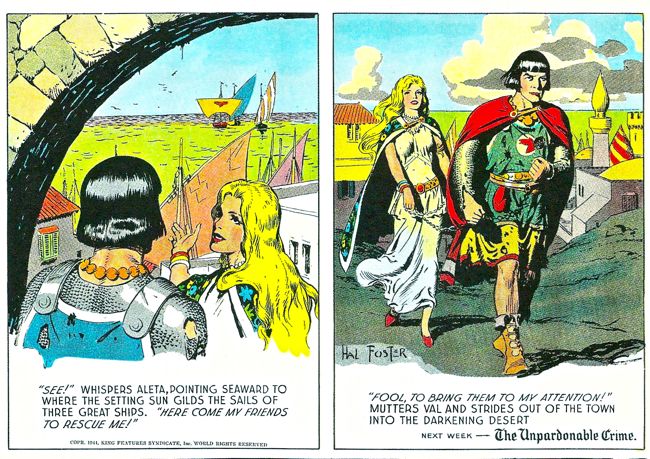

The final pages of this volume see the unsentimental humanism of Foster’s plotting at its apex. In a sequence that would put Stanley Kowalski to shame, Val storms the kingdom of the woman he has been pining over for years: Aleta, Queen of the Misty Isles. Landing illegally on her shores, the prince is attacked and sees his best friend cut down before his eyes. Between rolls of thunder and crashes of lightning, he carves a bloody trail to the throne room, where the queen is finally choosing a husband from the cast of nobles who have assembled to pay her suit -- a congregation, the text notes, that she has been dismayed over the past weeks not to see Prince Valiant among. But upon arriving, the prince does not fall to his knees before her in the kind of family friendly display of courtly love that Foster has been spoon-feeding to his audience for the past seven years. Instead, before the eyes of a dumbstruck retinue of attendants (as well as what must have been a shocked nation of newspaper readers), the hero grabs his destined wife by her flowing tresses and drags her across the ground back to his ship. The next day is Christmas, and a present is fashioned for the queen: a length of chain that will bind her wrist to that of her the man who loves her. “You will be led,” he tells her, “a captive, through all the kingdoms of the world.” She acquiesces, and from here on a smile is never far from her face.

The end of the volume finds Val and Aleta wandering the shores of North Africa, still lashed together by the chain, headed inevitably for marriage and domestic bliss, just in time to greet the post-WWII world. But no amount of restored normalcy can erase the climax Foster brings his hero to on these pages, the unforgettable mixture of seething emotion, unexpected action, and pure, consuming kinkiness rioting beneath these beautifully drawn pictures. For the final few weeks of 1944, at least, what Prince Valiant was doing qualifies it even now for the title it held so long. Lose yourself in this book’s last few strips and it's likely that at some point you'll think to yourself that you’re reading the best comic ever.