Reading the New York Review Comics edition of Dominique Goblet's Pretending Is Lying, I was reminded of an old Phoebe Gloeckner interview with Gary Groth in The Comics Journal. It's commonly believed that the harrowing experiences she depicted in A Child's Life and Diary Of A Teenage Girl are based partly on her own life. However, when Groth asked about certain events in the book and referred to them as happening to her, she very insistently deflected that line of questioning. She repeatedly said that it happened to the character she created (named Minnie) and not her, no matter how many times Groth tried to get her to admit to something that seemed obvious.

The reality was that Gloeckner was not being disingenuous, nor was she even deflecting. A narrative about a personal experience is a narrative, not the experience itself. It's mediated by the author. In a way, it's a kind of a lie, at least in the sense that when we pretend to play at something, it's a lie. This does not diminish the importance of these kinds of experiences; in some ways, it's easier to get at the truth through one's own textual avatar than it is through a supposedly "truthful" autobiographical character. Art is also artifice, and clever authors can show us the strings and matte paintings that make up their world while still making us believe in them because of their own skill and self-awareness.

Goblet's book addresses all of these issues and many more in a story that is deliberately complex, showing a number of people in her life at their very worst, and then flipping our understanding. Her drunk and neglectful father is at first set up as an unambiguous villain but later is depicted as far more compassionate than one might think. Her mother is depicted as a magical force for good in the beginning, but Goblet explores how her mother at times transformed her into something horrible. The pull of an old relationship threatens to tear apart Goblet and her boyfriend Guy Marc in a section in which they collaborated with each other in depicting how the scenes would proceed, even if it made them look bad. Ghosts and other things that don't exist take up prominent roles. People are warped into animal selves or made to look like Munch's The Scream. It's all pretend; autobiographical narratives are all pretend; and everyone is at least partly pretending.

Having established that, Goblet is able to go in some fascinating directions with the assumption that what's important about the stories in the book is not that they factually depict a narrative, but rather capturing the emotional truth of a situation. The book has four chapters, each of which represents a different emotional fragment of her life, with the first and third chapters and the second and fourth chapters directly connecting.

There's a lot that distinguishes this book from typical memoir. The partial collaboration with Guy Marc Hinant on some remarkably painful experiences is one, yet it's just another aspect of Goblet's mission in providing as many different angles on a situation as possible while demonstrating remarkable depths of empathy. Another is that the Goblet started work on the memoir in 1995 (when her daughter, a key character, was four) but was only able to work on it in fits and starts over the years, finally finishing it in 2007. The first chapter explores magical realist perceptions and has a painted wash over it that altered over the years. In that sense, the book reminds me of the Marcel Duchamp work The Large Glass, which took thirteen years to complete, spent some time gathering dust, and cracked in transit to its permanent home. That Duchamp had to repair it apparently pleased him, as though this was the final finishing touch. In much the same way, Pretending Is Lying started as one thing but wound up going in different but not dissimilar directions, as time altered her original art, her approaches to storytelling, and the very relationships she was examining during the course of the book.

Another non-comics work that Pretending Is Lying reminds me of is Bob Dylan's autobiographical Chronicles, Volume 1. Dylan, like Goblet, chose to eschew a simple, chronological memoir and instead jumps across time in his four chapters, spinning stories surrounding particular times and places. Each chapter expresses something important to him, and there are connections between the chapters for those looking. Similarly, Goblet is able to explore a lot of ground regarding her family by jumping around in time and building nesting narratives. The first and second chapters in particular feel like complete works on their own, the third feels like a true sequel to the first (it's even a direct continuation from where chapter one left off) and the fourth feels like an epilogue. Despite this level of artifice, the emotional urgency of each chapter is so powerful on its own that the structure disappears, leaving only that emotional impact.

The book's introduction features what appears to be a simple, sweet anecdote regarding Goblet and her mother. When walking outside with her mother, Goblet was going too fast and fell. In the process, she tore holes into her leggings, which made her greatly upset. Her mother took the leggings, pretended to fix them, and put them back on her daughter backwards, so Goblet could no longer see the holes. Her reaction was awe and mystification, but the reality was that this was a form of artifice. Pretending. Lying. All for a good cause, of course, but when compared to her mother's actions described later in the book, the "good fairy" effect fades.

The first chapter is a visual tour-de-force as Goblet masterfully establishes everything that the reader needs to know. We learn she has a four-year-old named Nikita, and that she's visiting her father (and stepmother Blandine) for the first time in four years. She stopped seeing her dad in part because he was a drunk. With that simple setup, she dives right into the dynamic with her daughter, her dad, and her stepmom. She draws her dad as this huge, bulbous, and slightly absurd figure and Blandine skeletal, and with a Munch-like perpetual Scream expression. The book's translator, Sophie Yanow (a formidable cartoonist in her own right), is able to get across some of the book's verbal jokes, like the fact that variations and diminutives of young Goblet's name mean "little nothing" or "dumb." Her father is a classic macho blowhard, bloviating like a politician and bragging about how much people love him and like to give him things, his greatness as a firefighter, etc. If you're not 100% behind him, then you become a potential enemy, and he sees his daughter as being in cahoots with his ex-wife.

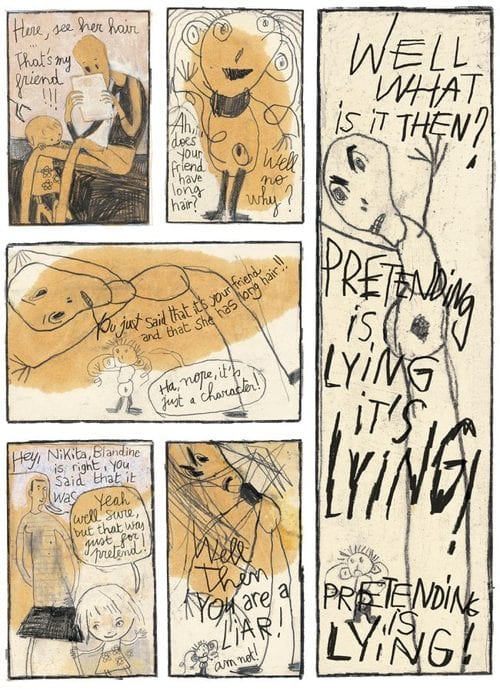

Goblet literally starts depicting her father as a bull when his rage starts to build, borrowing from medieval religious imagery. Her ability to merge her imagination with reality is at once seamless in a narrative sense and painful & raw (though beautiful) on the page. Her father is a powderkeg. Blandine is just as bad. When Nikita tells her that a drawing that she made wasn't really of her friend but rather that she was pretending, Blandine screams the titular line, "Pretending is lying!" over and over. On those pages, Blandine is suddenly drawn the way a child might draw an adult: raw lines and a looming presence. The chapter ends with her father claiming that he was abandoned by Dominique and her mother, while Goblet knows the opposite was true.

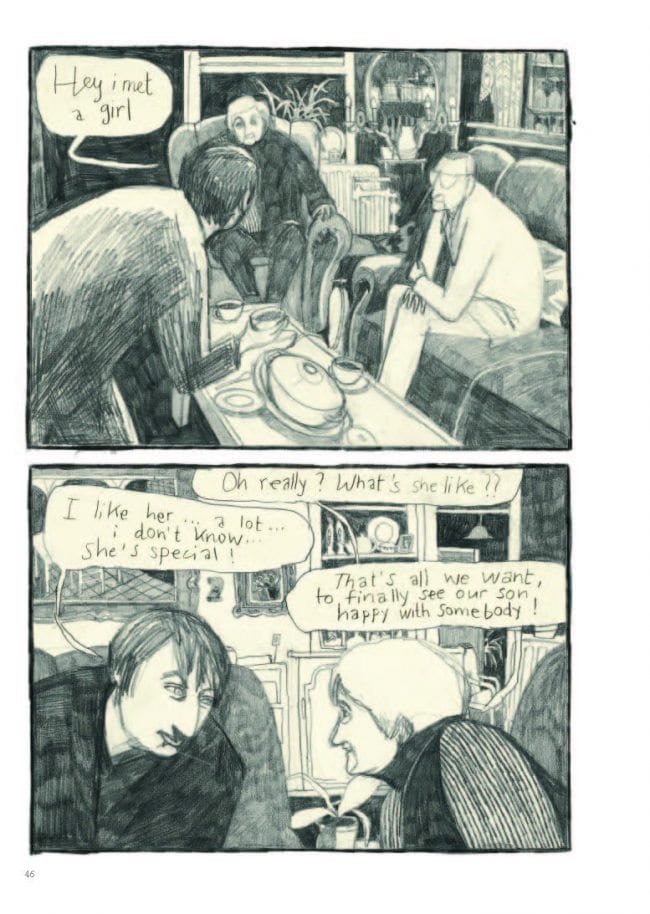

The long second chapter is all about ghosts. It begins with a story about Goblet's father encountering what appears to be a ghost that she was relating to her boyfriend Guy Marc Hinant; that spectral image of a woman haunting a space recurs throughout the chapter. Much of the chapter is told from Hinant's point of view (retrospectively) as he conceals from his new girlfriend Dominique that he's still very much hung up on his old girlfriend in a relationship that went sour. She moved on to another partner as well, but Hinant saw her behind Goblet's back and then boldly lied to her about it. There are a couple of clever establishing scenes that show the powerful connection they started to form, including funny banter in a grocery store and a sex scene where Hinant's desire is reflected in several small panels imagining her naked in numerous positions before he comes up to her and puts his hands down her shirt. This scene makes the other scenes that much more painful.

In fact, these pages are full of characters in pain, with Goblet coincidentally developing brutal migraines just as Hinant is seeing his ex. Hinant chooses not to be honest about what he wants, in part because it's clear that he's not sure. Goblet is tortured by his gaslighting and is constantly stressed and paranoid. Hinant's ex is drawn to him (and they both say words to the effect that they are the only ones for each other) but neither can make it work. It's a hellish limbo that's set off by Hinant's inability to figure out what he really wants and to control the reactions of everyone around him. The chapter is excruciating to read in many respects, but Hinant notes that the narrative is not the experience. Once again, artifice allows both artists to express painful feelings through their avatars on the page. By the end of the chapter, Hinant figures out that he can't be with his ex, that they've moved in different directions, and he needs to leave her behind before he's stuck forever. It doesn't make him happy, but he does grudgingly come to an understanding of himself.

Something else important happens at the end of the chapter. Goblet is informed by a family friend that her father is dead in a bizarrely humorous extended speech ("He's not doing well. He's not doing well at all. He might be in the hospital. It would seem he that he's dead."), triggering all sorts of emotions, but then she is told he was in a coma for a while and is now better. When she goes to see him, she confesses to him the problems with her boyfriend, and he proves to be caring and empathetic in his own way. This is another way of revealing artifice, because the reader had been made to think her father was one thing, and the reality is that people are complicated and messy. Her father was a narcissistic drunk and he also loved her.

The third chapter picks up right where the second chapter ended, as we get a flashback to Goblet's childhood when her parents were still together. Her father is off watching a race on TV on a rainy day, while young Dominique is bored, and her increasingly annoyed mother gets angrier and angrier at her for interrupting her housework. Though Goblet has abandoned the color and magical realist flourishes by this time, this isn't to say that the pages aren't fascinating. They provide a master class on the use of negative space, spotting blacks, and setting up grays to create mood. The use of shading helps create the claustrophobic character of their tiny apartment, and the way Goblet juxtaposes the scenes with herself and her mother vs those of her father talking to the TV are perfectly timed with the rising tensions in the story. When her mother finally explodes and starts screaming at her, the stories intersect, with her father rising to intervene--until there's a brutal crash on TV. He's distracted, in part because the fiery accident gives him a chance to fantasize about saving the driver, and partly because he is always distracted. The work of raising Dominique, it is implied, is always left to her mother.

And her mother makes horrible choices, locking her up in the attic and tying her arms so that they are suspended high above her head, the ropes tied to the rafters. In each of these scenes, Goblet juxtaposes the text of her mother screaming at her with drawings of the car on fire and blurry figures trying to intervene, and conversely juxtaposes the text of the TV commentary about the crash with crystal-clear images of herself in the attic, weeping and wailing. By the end of the story, the mother takes Goblet down and is calm again, putting her on her lap and playing a game with her after the storm has subsided. When her father enters the room, he is in the world of the crash, oblivious to anything else.

Returning to the present, the dinner at her father's house is a disaster when Blandine starts screaming at Goblet and demands that she let her daughter stay there. Blandine is not presented like a Munch image because she is monstrous or frightening. She's presented that way because she is in constant, unrelenting psychological pain. It's clear that some of that pain is of her own creation, and some comes from living with Goblet's father, but Goblet clearly triggers something in this visit, and it leads to a screaming match and Goblet's subsequent exit. The final image of her father driving them home, boasting about "Injection Turbo" and going fast is a perfect send-off for what is essentially an aged teenage boy, playing pretend.

The final chapter takes place some time later and begins with Hinant complaining about shoes that need repairing and being told he has to throw them out and get new ones. It is a hilariously transparent metaphor for his relationship with Goblet, which leads to intensive listening to the blues and then a call to her after his cat brings him a bird. He stumbles through a story about wanting her to see the bird (which has flown away) and then copping to the lie: he just wants to see her. Everything else in the story collapses into a single point—"When? Now."—as the paints suddenly resume and all figurework falls away. All of the pretending and lying falls away, even as he immediately admits to lying (the first time he does so in the book). There is just that one moment of desire, of longing, of sadness, of forgiveness, of love.