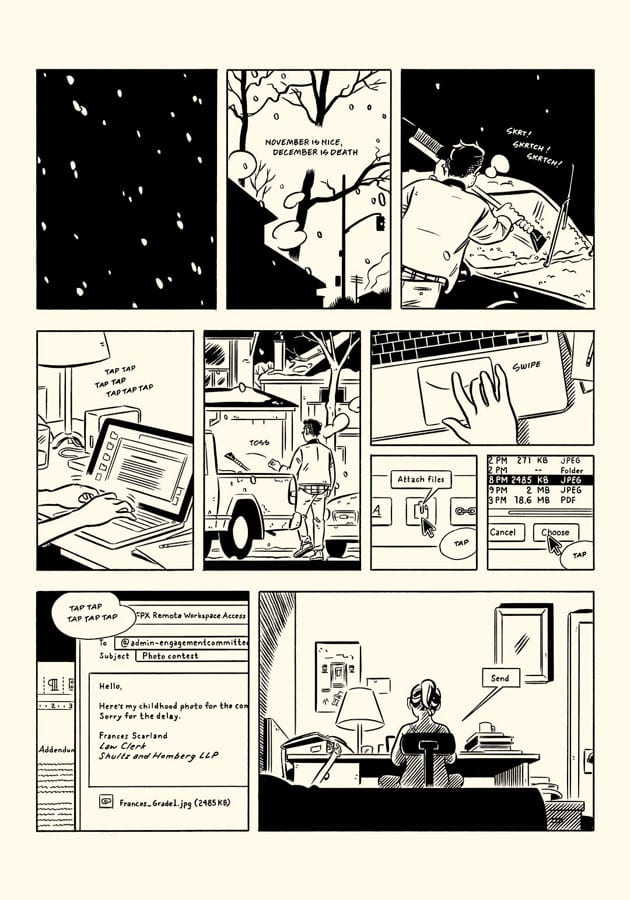

The saga of best friends and polar opposites Frances and Vicki comes to an end in a double-sized issue of Pope Hats, Ethan Rilly's catch-all, one-man anthology series. Unlike previous issues, which featured multiple stories, this one is entirely devoted to Fran and Vicki, the childhood friends who took dramatically different career paths. Fran's a twitchy law-school dropout who became a hyper-competent clerk in a high-powered firm; as she spun her wheels in this job, her competence, diligence and efficiency made her a desired property for the lawyers playing the game of performance and persona in their work lives. Vicki is a flighty actress who finally makes it big, moving to Hollywood to star in an absurd television pilot about a prosecutor who is also a vigilante. Both women, in this slice-of-life story that eschews cliché, are now living lives that seem to be happening to other people, leading to a sense of disconnection that they both manage in different ways.

Their relationship is the bedrock of the comic, and this issue explores its absence; their only continued tether is the occasional phone call. What Vicki has lost is the connection to sanity, reason and critical thinking that Fran represents. She's now operating in a sphere that's not unlike Fran's in the sense that everything is now a performance--and not just on set. Every move is calculated. Everyone is looking for an advantage or for someone higher up on the food chain to slip. Failure is mocked. All of this happens off-panel, but Rilly doesn't need to show it, because he's already spent four issues at the law firm portraying it. What Fran lost when Vicki moved was someone who could lighten her load and get her to stop disappearing up her own ass with anxiety and indecision. Someone to tell her that she was great when Fran hated herself, just as Fran encouraged her actress friend.

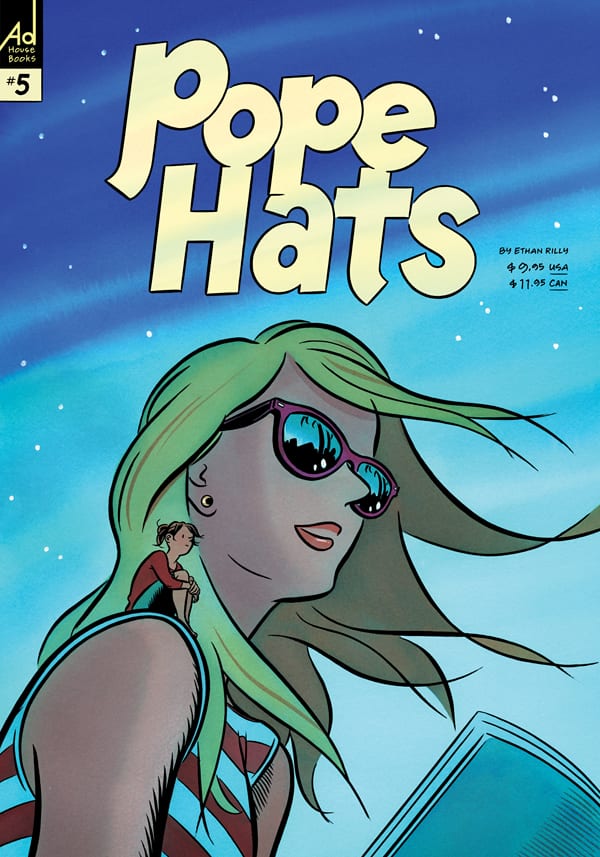

As such, much of this issue is really an internal struggle for Fran, as she tries to assert her own sense of agency. The cover tells a tale in itself: Vicki as a big star filling up the night sky (and yet still wearing sunglasses that reflect the palm trees of Hollywood) and a tiny Fran contentedly sitting on her shoulder, her knees drawn up to her chest. It's a funny image, yet it's exactly how Fran sees herself with regard to Vicki: someone small and mousy being friends with a larger-than-life personality. That also extends to how Fran relates to men, especially Peter, Fran's crush and Vicki's one-time fling. Fran responds to her feeling of disconnection by going ever more inward, and Vicki's response is to be bigger and louder.

Much of this story is about personal agency when faced with a culture that steamrolls indecision. Fran's integrity and lack of interest in playing the game of climbing the ladder (in part because she is too busy keeping herself busy to even notice that there is a ladder to climb) draws the attention of the scheming partners of the firm, with the mammoth Marcel Castonguay being the shrewdest and weirdest. Rilly has firmly settled into his own mature style, utilizing a cartoony, clear-line approach similar to that of Harold Gray's Little Orphan Annie. There are dot eyes, single lines for mouths, and in the case of Castonguay, blank circles for eyes a la Daddy Warbucks (by way of the Kingpin). That character's bulk plays a key role later in the story that emphasizes the larger-than-life nature of the character. The design for Fran herself is elegantly simple: perpetual pony tail, dowdy sweaters, slightly slumped shoulders, and a facial expression that rarely changes. That seeming blankness belies the stewing turmoil within, but it also allows the other characters to fill in what they want to with regard to Fran. Her only seeming friend at the firm turns on Fran when she learns that she is about to get a massive promotion, thinking that Fran is a schemer like everyone else.

Fran is not offered the promotion at her job so much as it is thrust upon her, with the assumption that she will take it. When she finally asks what would happen if she doesn't take it, her boss says, imperiously, "Nothing. Nothing at all would happen... you would float around like a spore while everyone else moves forward." Considering this is how Fran often thinks of herself, it is a comment that hit hard, but one that doesn't sway her. It's not until Fran realizes for herself that her employers are as human as anyone else, something that Peter and everyone else has tried to hammer into her, that she is able to move forward and make a decision for herself that brings her real satisfaction. It isn't just about work; it is about establishing meaning for herself outside of work (like expressing her feelings for Peter). The fact that this all comes about because of a classic trouser-dropping gag on the part of Castonguay amkes it all the better, as it brings full-circle the comedic elements of Rilly's style that he almost always keeps restrained. When the trousers fall and everyone pretends that nothing happened, it is a moment of pure, delightful absurdity. It is also a moment of vulnerability and humanity.

Hopefully, the whole story will be collected by AdHouse, because its focus on the specific beats of office life, of young people doing things not typically seen in stories about young people, and the incredible core relationship between two female leads makes this an unusual, beautifully told story with slightly absurd (in the existential sense) humor and razor-sharp dialogue. It's a story where Rilly's obviously extensive understanding of comics history and traditions eventually takes it in directions that are most effective in comics form, and that any other medium simply wouldn't have been able to tell the story with the correct degree of subtlety and restraint, as well as extreme and cartoonish exaggeration.