Did we take Richard Sala for granted? Magic 8-Ball informs me signs point to yes.

Upon his death I was surprised to learn he was 65 years old. That’s silly, of course. After all, he was in RAW - and not the Penguin RAW, sold in palettes at Costco during the buildup to the first Gulf War, but the real RAW.

Were you around for the real RAW? Well, put your hand down, you don’t get a cookie for being old. I should know! I’m no spring chicken either and yet Richard Sala was a presence on the comics scene for the entirety of my comics reading life.

Something about that kind of consistency seems to work against artists, at least in life. Artists who release good work at a regular clip often unintentionally silence themselves, establishing a high bar and maintaining such a sufficient level of quality throughout that they almost seem to become a part of the furniture. I never needed to wonder what Sala was up to. Seemed like there was always something or other being solicited, yet another volume of gorgeously illustrated damsels solving mysteries and fighting ghouls across German Expressionist cityscapes.

It’s wrong to hold an artist’s very consistency against them, and yet the fact remains that we do. Gil Kane was still doing random DC fill-ins up through the mid-90s which you could buy at your local gas station - if your gas station still stocked comics. I think about that a lot, actually - I got to buy new Gil Kane comics off the stand. Me! A mere stripling, still feels like. And I didn’t even appreciate it at the time, because he’d worked consistently, and at a superlative level of quality, for decades before I was born. And then one day there were no more Gil Kane comics, and there would never be another Gil Kane comic again, and you realized how much you should have cherished that when you had the chance.

Well, I probably should have paid more attention to Richard Sala. Because I hadn’t thought about him for a while.

Poison Flowers & Pandemonium is the volume at hand - subtitled A Richard Sala Omnibus, it offers a case for Sala as not merely a consistent but also an inimitable artist. He had a groove, ‘tis most certainly true. If you don’t see the appeal in glamorous ingenues menaced by various ghouls in various spooky locales, you may wish to seek elsewhere. While that generalization wasn’t necessarily true of all his earlier work, it is most certainly true of much of his later career. The scratchy, Panter-esque mark immortalized in Liquid Television’s Invisible Hands - as clear in his early work as the hand of Neal Adams in early Jim Aparo - was largely superseded by a more stable brush line and an expert eye for color.

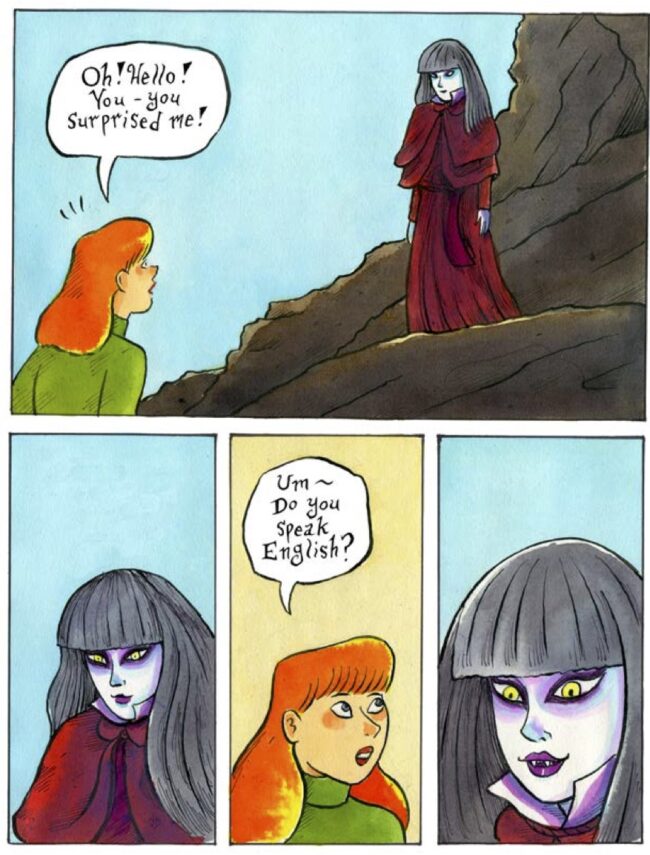

That said, while I would be loath to reduce Sala’s entire career to drawings of beautiful women, there is no doubt that one of the overriding artistic concerns of his life was drawing beautiful women. There are but a mere handful of non-text pages throughout the present volume that do not have drawings of beautiful women in them, mostly clothed and very plucky, often in the throes of some manner of stirring adventure.

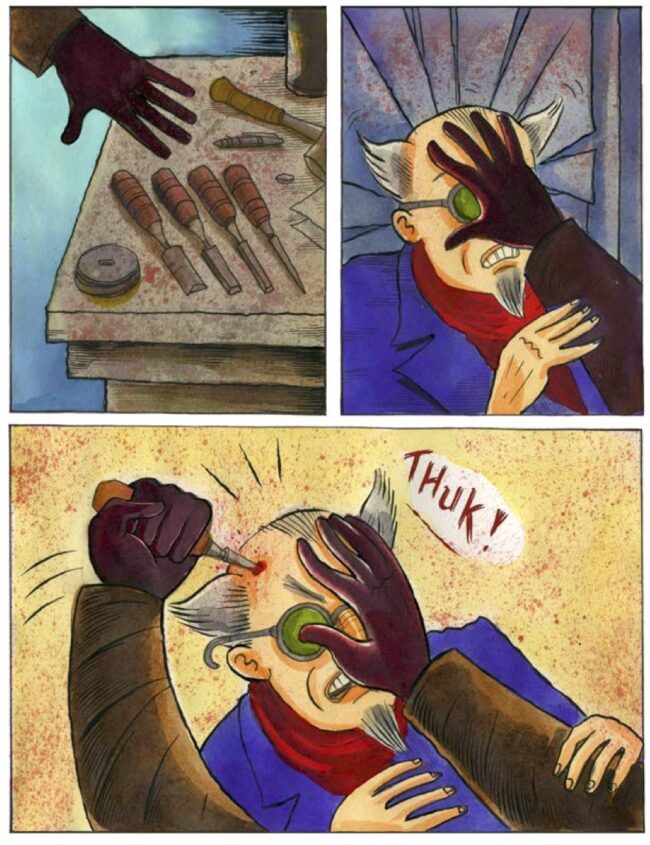

The first feature and the longest is a sequel to a previous volume, 2017’s The Bloody Cardinal, entitled House of the Blue Dwarf. The title character is a deadly vigilante, formerly a hero who went bad and never looked back. He’s barely in the story, which is more concerned with teen psychic Phillipa Nicely, the center of a previously unrevealed Venn diagram mapping the overlap between Jean Grey, Daphne Blake, and Nancy Drew. She’s having weird dreams about mummies in Aztec tombs while the Bloody Cardinal has been cutting a bloody swathe through the underworld. There’s a lighthouse on the beach, and a dream filled with fetching lady castaways dueling each other to the death prior to being eaten by a vampire. There’s honestly a lot more plot than I’m explaining - frankly, too much plot! Most characters end up stabbed, it’s that kind of party.

From another perspective, I suppose, it might be easy to draw a slightly less flattering profile of Sala’s career. Say, for instance, you weren’t one for books filled with drawings of winsome lasses - why, you may even have groaned at my reference to “winsome lasses.” I freely acknowledge my bias in the matter - I have quite a high tolerance indeed for drawings of beautiful women and tend to forgive a lot in the interest of same. Is it a critical blind spot?

Which sounds like a joke, but I want you to consider for a moment that previously mentioned slightly less flattering profile of Sala’s career. This is not to disparage the man at all, on the contrary. The evidence of Sala’s career is marked by consistent improvement in technique and development of style. He was a prolific commercial artist, owing to early success and timely involvement in some very influential publications. But could you have read his earliest work and seen his Liquid Television segments and thereby predicted, oh yeah, that guy’s gonna do like a foot tall pile of books about cute girls solving mysteries and fighting monsters? I dunno. Maybe you could. It’s not all he did, but he sure did a lot of it.

There’s a larger point here, however, in the fact that so much of Sala’s work - his later work, specifically - was devoted to plowing a very specific field. He loved silent movies, Fantomas, Edward Gorey, Famous Monsters of Filmland. It’s a recognizable and fertile vein, similar to that popularized by the likes of Tim Burton but hardly exclusive to film or fashion. Sala seems distinctive on account of appearing very near to goth without ever actually being goth. I think it has something to do with the fact that even if they utilize the same primary sources there’s no hint of punkish confrontation with the present, only nostalgia. Sala’s list of genre referents stops more or less at the 70s, with a small dollop of Hanna-Barbera. His pastiche is loving and very idiosyncratic.

And therein lies the problem, I think, in terms of considering how exactly to approach Sala’s work. There’s a generational disjuncture in the approach to genre, in terms of the conflict between form and function. Older generations of artist were far less critical in the precise replication of the form of genre tropes. What that means in practice is that something like Sala’s present volume is filled with images of the kind of spooky stories and adventure yarns that he liked growing up - a pile of influences from the early and middle of the twentieth century. Those images are occasionally dated. I winced at the horrific pigmy tribe in “Cave Girls of the Lost World.” Did it ruin the feature? No, of course not. But it was notable inasmuch as the rest of the feature was more or less unobjectionable. Unless of course you were the type to take objection to cave girls fighting dinosaurs.

Personally I find little objectionable in Sala’s women. It’s about the least sleazy kind of cheesecake you can imagine - hell, it could have been a tid bit more lurid. Even the aforementioned cave girls are all college-aged, nothing hinky whatsoever. Stuff like that ages well. Every art museum in the world will attest to the fact that pictures of pretty folk never go out of style and require no translation. But then something like, say, the aforementioned Blue Dwarf . . . Well! Someone younger than myself (and there are a few of those around) picking up the book isn’t likely to have any kind of nostalgic connection to this specific mix of 20th century cultural signatures. They don’t see the blue dwarf and think, ah, an unfortunate stylistic coelacanth of another era. They may have no connection to the primary sources, or even a familiarity with anything other than second or third order aesthetic descendants. There’s no longer any cultural incentive to tease out the attempted function from the dated form.

Frankly, when it comes to dated references to dwarves and evil pygmies, it’s a good thing if the incentive to rationalize is lost. Second-hand nostalgia is a hard thing. It’s not that it can’t work, and work well. It’s a time-tested tradition. The problem is precisely the disjuncture between what the story is trying to do as opposed to what the reader actually sees it doing. Some degree of translation is always necessary to carry the past into the present, to make of nostalgia more than recitation. Sala’s style does a good job of synthesizing a great span of influences into something uniquely his own. What sticks out as indigestible are those areas where the meaning of symbols have changed in the ensuing decades, or rather become clarified to the point where they present a distraction to drown the creator’s intention.

And it would be a shame for those small distractions to overwhelm the groove because Sala’s groove is pretty cool. There’s not a drawing in this book that isn’t worth lingering over, tracing the brushstrokes. The Bloody Cardinal is a dude with the head of a red bird who jumps out of wardrobes to chop peoples’ heads off with a machete while screaming “It’s your ticket to hell!” Do you get what I’m saying? Sala knew what he was doing. When these stories cook, they really cook. He understood full well what this kind of twisty-turvy thriller was supposed to do. He sincerely loved this stuff. He knew how it should feel, what the stories needed to do to hit the right marks. He also knew how they should look, and that works well except for a handful of instances where obeisance to outdated form sticks out.

The book’s final feature stars Fantomella, a daring thief with purple hair creeping through the night and tearing a bloody swath through the underworld with two daggers. Gonna be honest, my first thought when I saw the character was, hmm, that design looks a lot like Kwannon, least back when she first appeared in X-Men (Vol. 2) #17. Surely a coincidence, given the dearth of any more contemporary referents in Sala’s work. There are after all only so many ways you can draw a purple haired super chick doing sick ninja shit. But honestly? If you like seeing purple haired super chicks doing sick ninja shit the comparison is fucking apt. Fantomella could probably kick Psylocke’s ass.

See, that was Sala’s charm: he was fun. He was in RAW and saw his work published across the industry’s most prestigious venues - how many artists can say they were in both Playboy and Nickelodeon? Pretty much scaled the pinnacle of what is possible for a successful cartoonist. And after doing all that, he decided that what he really wanted to do was draw purple haired super chicks doing sick ninja shit. Does that make sense? Is that an unflattering description of his career trajectory?

Seems the wisdom of the ages, to me.