I have to admit, this is exactly the sort of work that gives me a crisis of confidence regarding what the purpose of reviewing even is. Not because it’s bad, but because it’s good. Frank Santoro’s Pittsburgh is a poetic and deeply-felt exploration of how we are shaped by barely-knowable histories of family and place, made by someone who is clearly a master of their craft. I respect it very much.

And yet I can’t imagine myself returning to it, and I can’t imagine telling someone that they have to read it. But is that really a criticism of it? Why does that feel like a criticism of it? Shouldn’t it be enough for a work to simply be true and good? What does it matter whether it personally inspired me, if the author successfully expressed what they wanted to express?

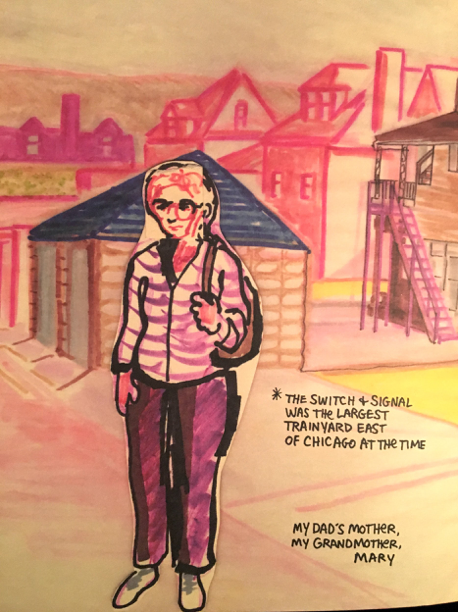

The strength and the weakness of Pittsburgh is that Santoro has clearly mostly made it for himself. He even says so explicitly: “I started out to write a story for my mother...But I ended up writing the story for me.” The book details Santoro’s attempt to come to grips with the fact that his parents, despite living in the same city and working in the same hospital, have barely communicated with each other in twenty years. In order to understand, he goes back to 1968, when the two of them were high school sweethearts in working-class Pittsburgh, and paints the picture of their lives. His mother Anne-Marie, homecoming queen and the oldest daughter of Irish alcoholics, forced to play parent to her younger siblings. His father Frank, 19 years old and a soldier in Vietnam, traumatized by an incident in which his entire squad is killed while he’s on leave in Hong Kong. The two of them eloping to avoid Anne-Marie’s family’s disapproval.

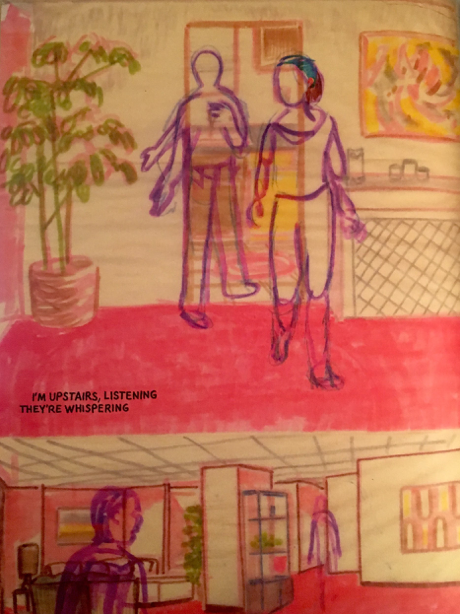

Santoro then skips ahead to 1977, 1996, and 2006, documenting the conversations he has with his parents and the people close to them, and the piecemeal information he receives about why they are now so completely estranged. We never do get any sort of dramatic explanation for why Santoro’s parents don’t speak. Just simple, human explanations, like Frank not being ready to have a family so young, and Anne-Marie resenting that the man she loves wanted a divorce.

On one level, the simple, personal nature of this story is a strength, because the unsettling adult experience of family archeology remains unsettling no matter how flamboyant one’s family story. Not everyone has a family that sounds like it should be a book, but most everyone is still influenced by the places they grew up, and the people by whom they were raised. When those people and places change, it can be hard not to feel like something about one’s self has changed as well. When those people don’t communicate with each other, it can be hard not to feel like parts yourself aren’t communicating either. And there is a shifting, unsteady quality to both the art and the story in Pittsburgh that deftly captures this sense of unmooring. In one memorable sequence, Santoro goes for a bike ride with his father as an adult, and his father casually mentions that the reason that Anne-Marie’s family didn’t come to their engagement party, the reason that they had to elope, was because he’d slept with another girl. I know exactly what that sort of moment feels like, and the quiet whiplash of it hits exactly right, because up until that point in the book, we only know as much about Santoro’s parents as Santoro himself does. It’s difficult to capture the way that the slightest, laughed-off revision of one’s family history can drastically alter one’s sense of reality, even when it doesn’t seem like it should. And Pittsburgh does it well.

On one level, the simple, personal nature of this story is a strength, because the unsettling adult experience of family archeology remains unsettling no matter how flamboyant one’s family story. Not everyone has a family that sounds like it should be a book, but most everyone is still influenced by the places they grew up, and the people by whom they were raised. When those people and places change, it can be hard not to feel like something about one’s self has changed as well. When those people don’t communicate with each other, it can be hard not to feel like parts yourself aren’t communicating either. And there is a shifting, unsteady quality to both the art and the story in Pittsburgh that deftly captures this sense of unmooring. In one memorable sequence, Santoro goes for a bike ride with his father as an adult, and his father casually mentions that the reason that Anne-Marie’s family didn’t come to their engagement party, the reason that they had to elope, was because he’d slept with another girl. I know exactly what that sort of moment feels like, and the quiet whiplash of it hits exactly right, because up until that point in the book, we only know as much about Santoro’s parents as Santoro himself does. It’s difficult to capture the way that the slightest, laughed-off revision of one’s family history can drastically alter one’s sense of reality, even when it doesn’t seem like it should. And Pittsburgh does it well.

The artwork in Pittsburgh is sketchy and sometimes crude, but with a clear confidence in the line and color work that tells you Santoro is doing it on purpose. The book is made with a child’s materials—markers, colored pencils, construction paper, tape. It has the look of a scrapbook, or a childhood project. There are many places where it appears that revisions have been tacked on, or a character has been inserted into a setting like a paper doll. Almost every illustration is highly layered, with outlines and underdrawings, and people and places, all visible simultaneously. There is something nearly Cubist about it, in the way that it flattens multiple levels of reality onto a two-dimensional page.

It all fits very neatly with what the book is about. Reality is indeed a layered thing. As a person changes, or a city changes, those changes tend to be accumulative, stratigraphic. And of course, looking back at one’s past is always going to be undermined by the inherent frailties of memory and perspective. Of course this story is framed through a child-like lens, and of course the details aren’t filled in. That is often how it feels to look back and try to make sense of where you came from, and how it led to who you are.

Here’s the thing: any work of art has to find its own balance between being for the artist and being for the audience. Between expression and communication. But nowhere is this tension more obvious than in art that is about an artist’s life or emotions. It’s instinctual to think of personal art as dangerous or daring, because talking about oneself is inherently vulnerable. It involves revealing something private, which is often a difficult thing to do. But because the author is the only person that has any authority about their personal experience, it is also difficult for an audience to argue with it, to have a relationship to it. An audience can’t say whether the work does or doesn’t feel true, because they don’t know the truth. They can’t say that a painting is a “wrong” expression of how an artist feels, because how would they know one way or another? They can’t know why they should care about the artist’s emotions until the artist convinces them. They don’t have the context of the artist’s life unless the artist provides it.

In other words, personal art runs the risk of prioritizing expression, when it requires as much (if not more) communication as any other genre if it is to reach its audience. When a work prioritizes expression, there is something that can feel “safe” about it, because its success or failure doesn’t depend on how it’s received. When I think of great memoir, “risky”-feeling memoir, I don’t think of memoirs with lurid hooks, or even memoirs that simply feel true to the artist’s reality. I think of memoirs that contextualized that reality for me. I think of books like Caroline Knapp’s Appetites, which used her experience of anorexia to talk about the female relationship to denial writ-large. I think of Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, which uses a twisty, pseudo-fictional, psuedo-autobiographical relationship to reality to talk about both the experience of war, and narratives about war. I think of Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, which describes Bechdel’s family life in intensely allusive terms that make their intimate dramas of death and sexuality feel part of a grand human struggle of trying to turn emotion into art.

So my feeling while reading Pittsburgh was that while I thought that Santoro had rendered his experience in an evocative, expressive and, by all appearances, emotionally honest way, it didn’t feel like he had fully transformed that experience for my benefit, that he had processed it into something that I could walk away with. It felt, instead, like I was being made privy to his personal therapy, exalted into art though it was. And so I suppose the question comes down to: am I, as an audience member, owed something other than that? Technically, I can’t argue that I am. If writing Pittsburgh only helps Santoro, then the world is better for it existing. But how could I not want something more from it? That’s what I consume art for, after all. The greatest memoirs I’ve read have all been intensely personal, reflections of the artist’s attempt to resolve something important to them. But by putting the artist’s experience in the context of something bigger, they left me feeling like I too had resolved something. They left me transformed the way all great art does. Pittsburgh may have succeeded at being that for Frank Santoro, but in its success, I’m not sure who else it’s for.